Hammered

Academic life and feeling flat

Regular readers may note I have not written many posts lately. I have about fifteen unpublished, unfinished posts. They will remain unpublished. No one wants to read posts written when I’m miserable and angry. Well, no, that’s not true. Actually I could probably build a huge audience! But that’s not what I want. For people who tell me that I let it all hang out: no, no, you haven’t seen unfiltered Katy. Let’s not go there!

People love polarisation, and egg on authors to more extreme positions: that’s how you get audience capture. However, I am not writing this blog to get a huge audience or to further polarise people. I’m not even quite sure why I’m writing it, except to think my own thoughts through to the end, to share interesting things I find, and to (hopefully) make you think.

A significant reason for my recent misery is the polarisation I’ve seen in broader society, and particularly in academia and on campus. People take radical, entrenched positions, and anyone who disagrees with them is automatically in bad faith. And if you believe that anyone who disagrees with you is evil, you will not listen to them and dialogue is impossible. This seems to me to be inimical to the scholarly mission. We learn through discussion with others.

Another reason I have been depressed is because I continue to feel that academic institutions are foundering. I note that two government reports in Australia (here and here) have recently concluded that there are huge issues in university governance. I concur. As managerial class grows, and is paid more, the student and staff experience seems to just get worse.

However, I remain unconvinced that any of the proposed reforms will fix the underlying problems. In any case, as my colleague Emeritus Professor Ian Ramsay notes, some of the proposed solutions are not consistent with one another. Lessening the reliance on management consulting firms, and changing the way the upper echelons operate, is a start, but only a start. Greater transparency is also really important.

But there are much deeper problems, created by the bureaucracy of the modern academy and the incentives which guide our research and priorities. As Charlie T. Munger has said, “Show me the incentive and I’ll show you the outcome.”

Bureaucracy and the principal-agent problem

I teach private law, an area where it is increasingly difficult to find other lecturers. Many of the colleagues who might help me co-teach these subjects are going back to practice, and I understand why. Although I absolutely love the teaching and research, for the past few years, I’ve felt as though the kind of work I do might be valued more by practitioners. Perhaps it’s no surprise that we have a succession problem in private law academia across the globe. There are not many young private law academics coming up through the ranks.

For many problems which arise during the teaching year, these days, the first port of call is “online self-help”, or some kind of communal email or help desk, for both me and my students. The number of students increases, while the support for lecturers who teach large subjects falls. The students become unhappy. Meanwhile I receive complaints about matters I can do nothing about, all accompanied by a background burden of online administrivia and tortuous training modules which are more about signalling that “something has been done” than about anything else. It is disheartening.

Who bears the consequences of the way in which the university is managed? The answer is the students, the administrative staff, and me.

Who made the decisions which placed me in this position? Bureaucrats within university leadership who earn three times what I do.

What happens if the decisions which university bureaucrats made were disastrous and made things worse for both staff and students? Nothing. Let’s suppose that their KPIs simply required them to “streamline and centralise administrative processes” and “increase EFTLs.” Tick! ✅ They met their goals!

For the uninitiated, EFTSL stands for “Equivalent Full Time Student Load”, and is a term used in the Higher Education Support Act 2003 (Cth), and defined in s 169-27 of that Act. The particular division in which this definition is present is Division 169, “Administrative requirements on higher education providers”.

Do you see why I am somewhat cynical about the prospect of government regulation fixing problems with higher education? It’s a very Australian solution—“regulate it within an inch of its life”—but in this instance, I believe that the bureaucratic hoops set up by government contribute to the problem. They cause university administrators to be more focused on ticking the boxes in the legislation so that they don’t get in trouble with the government, and less focused on… well, actually making things work for those at the coalface.

More fundamentally, the current governance structure sets up a situation of moral hazard. The people who make the decisions about the administration and governance of the university (namely, university bureaucrats) are not the ones who suffer the consequences if those processes go wrong (namely, students, lecturers, administrators who assist students and lecturers).

In economic terms, this is a principal-agent problem: the person who exercises the decision-making power and has all the resources is not the one who bears the risk if that decision goes wrong. Consequently, there is information asymmetry, or in layperson’s terms, a lack of a feedback loop. Bad decisions might be made, which make a university worse, and those who are responsible for making those decisions do not bear the risks of those decisions. Indeed, the consequences of those decisions may take years to come down the pipeline, by which point, the bureaucrats who made the decisions have likely gone elsewhere.

Large bureaucratic organisations also have other issues. A colleague and I were chatting privately, saying that among some right-wing commentators, there is likely a view that university bureaucrats are all “social justice warriors” with blue hair. In our experience, this is not the case.

What do bureaucrats want? They want a given problem not to be on their desk. And how do they achieve this? Take the path of least resistance. Give in to whoever shouts loudest, to get the problem to go away. The fact that this may not be ideal for the university is not to the point. The point is that the problem has gone away. Tick! ✅ This incentivises university bureaucracies to bend to the demands of obsessive people with axes to grind. Whoever has the shrillest voice often wins.

To be clear, I don’t blame bureaucrats for this. It’s both painful and tiring to stand up to difficult people, particularly if your institution doesn’t incentivise pushing back against them. It’s much easier to give in.

Lately, I’ve been thinking of the Japanese phrase, 出る釘は打たれる (deru kugi wa utareru): “the nail that sticks out gets hammered down.” Suffice to say, I feel that I’ve been hammered in the last few years for insisting that various problems within the university were not shoved under the carpet. It can be utterly thankless to stand up. Often, the nail that sticks out is regarded as the problem: a negative person who is not a team player, and who won’t just keep quiet like everyone else.

Several people have said, “Well, I guess you’ve learned your lesson: don’t stand up for others, because you’ll just suffer. Next time, stay quiet.” I don’t even know if I should write this post. Maybe I should just stay quiet and say nothing. All I’ve done is create a lot of trouble for myself. People say, quietly, “You’re so brave.” No, I’m not. I’ve simply got a possibly terminal tendency to think out aloud and question. I thought that was people wanted in an academic, but maybe it’s not, these days.

I’m not trying to be negative or difficult. I’m trying to be Reviewer 1: that person who makes your paper better by being critical and pointing out problems in a constructive way. Better you hear from me than end up pilloried in a newspaper. I love teaching and my students. I want things to work, and I want my students to have a good classroom experience.

Incentives: grants and sexy topics

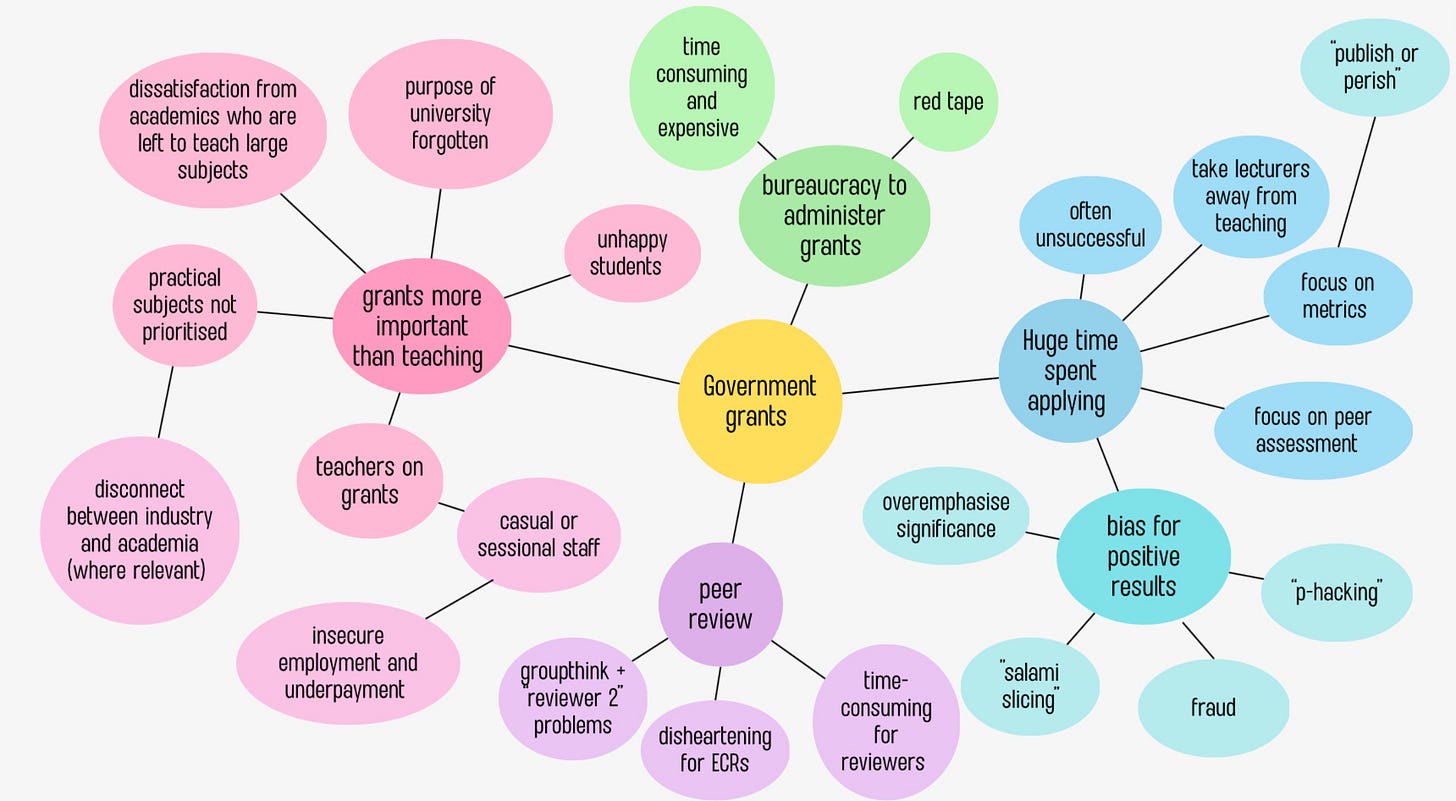

Another reason why I do not think any governance reforms will succeed is because they do not get to the heart of the issue. The heart of the issue, in my view, is that government grants distort the academic mission.

This is not the intention of such grants. The intention is to fund useful research, and often, they do so. Many colleagues have produced excellent research using grant money. However, it means that universities focus on doing things which maximise their chances of getting grants, often to the exclusion of other core duties.

Teaching established subject matter or writing textbooks is not a way to get grants. The way to get grants is to publish like a maniac—“publish or perish”—and be able to present your topic in a way that is appealing and worthy of funding. As this post by Rob Kurzban indicates the incentives of academic publishing require two things:

First, to be published in a top journal, the work must be new. For example, publishing a replication of prior work is vastly more difficult than publishing new studies. This fact explains why replication has historically been so rare: there’s a very low payoff to the researcher. Many observers of science have wondered about this because in their middle school science classes, they were taught that the foundation of science is replication. The Royal Society’s motto, nullius in verba—take no one’s word for it—is testimony to the point. Science requires checking other people’s results.

Second, in the social sciences and the humanities, the focus of the rest of this essay, work is likely to be published to the extent that it is counterintuitive. If you send a paper to a top journal saying, people like sweet things, you won’t even make it to the peer review stage. The editor will send it back with a polite note that says, in so many words, my grandmother could have told me that. No news.

The same is the case in law. New theories and new analytical structures are rewarded.

Although the intention of the grants process is good, other incentives and flow on effects may also be perverse, as I have discussed. Certainly, the grant process adds to the need for a burgeoning bureaucracy.

I recently taught a Masters’ subject, but I was not teaching in my normal rooms on Level 6. In this other room, I spotted these cartoons on the wall. They were drawn by a former student: I’ve blanked out the name of the artist because the intention of this post is not to criticise the artist.1 Someone—maybe a human rights lawyer?—had colour-photocopied the cartoons, blown them up, and put them on the wall as paintings.

The grant, publishing and academic promotions processes incentivises academics to present themselves as superheroes, saving the world from evil. Saying, “I am going to promote legal theories which result in a more just society and save people from being oppressed” sounds sexy as hell, right?

Saying, “I am going to present a nuanced and balanced discussion of allowances for skill and effort in accounts of profit” does not sound very sexy. … Well, actually it really does sound great, to me, but I may be unusual. I hope it will be useful, but I don’t feel that usefulness is valued in broader academia. It’s the new and outrageous.

We do better in promotion and grant processes if we over-egg our puddings. I have started wondering if this contributes to the polarisation we see on campus. We want to be superheroes, on the side of Good, not Evil. Who wants to be a defender of Breach Man? Indeed, we can’t even be silent about his crimes: silence is violence. In some campus milieus, if you refuse to call out Breach Man vocally at all times—even if Breach Man is not relevant to the topic you’re discussing—you’re complicit in his wrongs.

I shouldn’t feel too sorry for myself: “first world problems.” I showed the cartoons to a friend who can never go back to his birth country, because he will be gaoled. The reality is that if you are a sticky nail in places ruled by authoritarian regimes, you and those associated with you will be hammered (and unfortunately, sometimes you will pay with your life). Despite this, my friend has a nuanced view of people who live under this authoritarian regime. He looked at these cartoons and said, “Anyone who believes that has never put themselves on the line.”2

I suspect that those who pursue people like my friend do not generally go around cackling, saying how evil they are. Indeed, I’m pretty sure that at least some believe they are utterly morally in the right: that they are saving their society from dangerous ideas imported from a hegemonic and racist Western society. I wonder if they see themselves as superheroes, and my friend as a traitorous Breach Man. Others are likely just keeping their heads down, doing their jobs, and trying not to think about things too much (see the comments about bureaucracy and living a quiet life, above).

For me, one of the most worrying possibilities is that I may commit a wrong, even though I think I am doing the right thing. I do not have the arrogance to believe that I am a superhero, or that I own morality, and that I know better than anyone else how to organise a just society. It behooves me to be humble and to question what I do, and take feedback from those who think differently from me, because it is only in that way that I can learn and grow. It is really important for academics to be able to admit that they were wrong.

We need to reset academic incentives. We need to ensure that teaching and custodianship of existing knowledge is valued as much as new research and theory; that it is seen as virtuous to admit error; and that free exchange and respectful discussions are incentivised, not polarised rants. It is only when this occurs that the problems with academic institutions will be resolved.

Heck, for the first month of my law degree, before I knew any actual law, even I wanted to be a human rights lawyer. Then I started to learn the law. I’m told I proudly announced in History and Philosophy of Law that I was a positivist. I don’t recall this, but it is the kind of thing I would do. I remain a Razian positivist to this day. In other words, I believe that the law is a human creation and all its sources are human: statute, judge-made, and custom. This means the law is bounded by public acceptance, including rights. Rights are not zero sum. I might assert that I have a right to scream as loudly as I want, and you just have to put up with it (zero sum). However, I also owe obligations to you, which may mean that my rights to scream as loudly as I want is restricted if I am next to your house, given that you also have a right to quiet enjoyment of your property. Rights can be cut up like pie.

Well, actually it was a bit ruder than that, but let’s keep this professional.

Katie, you have almost exactly replicated my conversation with a colleague yesterday. An irony is that as govt funding of universities has declined regulation by govt has increased. The concept of academic freedom is a joke when we are so beleaguered by bureaucracy that we can't get to our real work. It has occurred to me that if my university got rid of its 20 or so pro vice chancellors it would save at least 20 m dollars a year and make our work easier because what they do is think of things we can do to justify their existence.

I want my students to feel that they can argue with people they disagree with so that the nuances and details of the arguments and views of the people come out and we all learn. I want to feel that I can say what I think without someone saying I am evil or an idiot. In the last couple of years I have been hammered a lot, and, like you, many people have come and said quietly, 'I'm glad you said that' because they felt afraid. I know I am relatively safe and if I got sacked I would be ok, but it grieves me that my colleagues often feel like this.

In my own way I try to fight - I say what I think, and I push back on all those courses they make us do ( they are so poorly designed it's a joke) but the pushing back sometimes risks hurting our administrators who are mostly working way beyond the call of duty.

I also wonder if people have forgotten what universities are for, but I think it's very important that people like you ( and me) continue to doggedly say what we think it's all about. Who knows, sometime the tide may turn.

I cannot begin to tell you how significant I think your contributions to things like this blog are ( not to mention your great research !). So don't stop!

All the best to you. Prue

Reading your posts on academic law always makes me think of the Shoemaker and the Elves – it’s as though I’ve walked into my own brain to discover that all my scattered, half-formed thoughts have been beautifully and cogently arranged. Thank you, and I’m sorry you are having a hard time.