More than a pat on the head

The problems in academia

I may as well confess it right now: irritation has a significant role in my productivity. From my prodigious output, you can glean that, despite my smiling face, I am secretly quite an irritable person. The other things which contribute to my productivity are an intense curiosity about everything, and a desire to show others what I’ve discovered in my exciting quest for knowledge, just in case it’s helpful. If I were a dog, I’d be a Jack Russell terrier.

The immediate cause of irritation in this instance was this article in Nature, entitled ‘Fed up and burnt out: ‘quiet quitting’ hits academia’. I don’t disagree with the fundamental premise that academics are fed up and are burning out, or that people are ‘quiet quitting’ (i.e. generally doing less extra work than they used to). On an anecdotal level, I’ve noticed it with colleagues. What annoyed me was the suggestion that more recognition of the work by bosses could fix the problem: praising someone for getting a grant, or a good review from students. It’s true, it’s good for one’s hard work to be recognised.

I don’t think that’s enough, however. There are deeper systemic problems. First, it is necessary and healthy to have boundaries between one’s work and home life, and we should recognise that.

Secondly, is the award of a grant, or a score in a student survey, a good way to measure of our worth as academics? Is the quantitative approach to success in academic working? In other words, are the incentives and markers of success in academia a systemic problem? I am starting to think that the answer to the last question is yes.

Academics are assessed quantitatively all the time. How many citations did you get? How many papers did you publish? How many students assessed your subject as “well taught”? How many grants did you get? How much was each grant? These numbers are taken as a proxy for a qualitative assessment, but they are not necessarily a good proxy. The quantitative and the qualitative are increasingly elided.

I doubt I’ll be popular for saying this—I am biting the hand that feeds (or is it feeding the hand that bites?)—but, as I have adverted to in an earlier post, I think a lot of the problems in academia stem from government funding of university and its research, and specifically the way in which grants tend to be awarded.

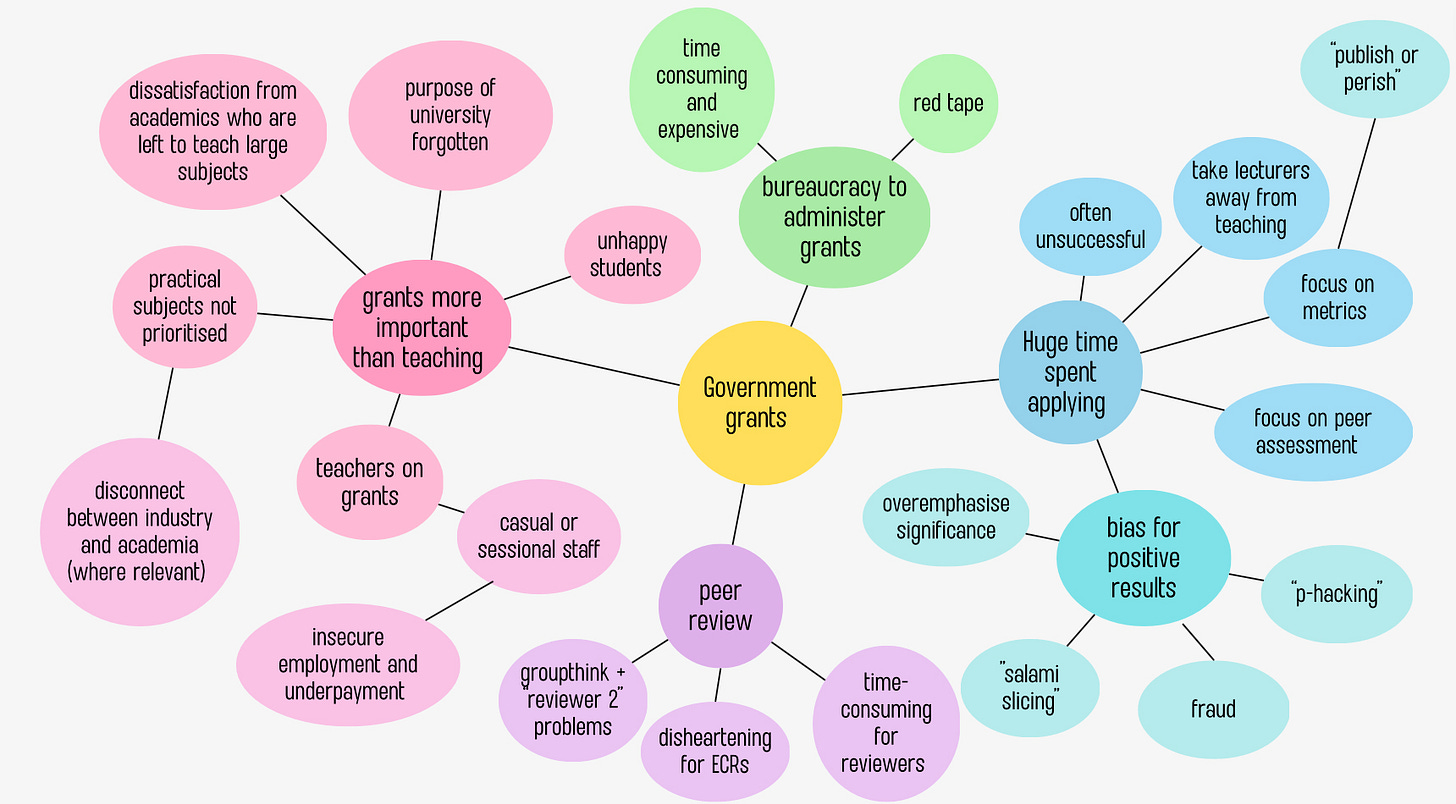

I’m not usually a fan of “mind maps”. As an aside, it reminds me too much of corporate training in law firms (just add in butcher’s paper and a request to form a group with the people at your table). However, I did find that there was no other way in this instance to illustrate in one fell swoop the unintentionally perverse incentives of the government grant system. So here you have my mind map:

I should emphasise that the idea of the grant system is a good one, with very creditable aims. Grants can—and do—lead to the production of important research. I am not suggesting that work produced by grants cannot be both useful and of good quality. Many of my colleagues have produced excellent work using grant money. I’ve just relied on an analysis produced by a colleague via a grant. I do not intend to criticise these colleagues in the least.

The methods by which grants are awarded do, however, produce perverse incentives, and these have to be faced squarely, particularly when academics are burning out or quitting, when there are problems with casual employees being underpaid or over-relied upon, and a burgeoning bureaucracy which sometimes seems to add layers of red tape rather than value.

In order to get a grant, you have to have a high number of publications and citations (which proves your work is “worthwhile”). This incentivises the competitive and exhausting “publish or perish” mentality which causes academics to burn out. Publish or perish can also create incentives for bad actors to game the system, as Stuart Ritchie points out in Science Fictions, where he describes the problems with fraud, negligence, bias and distortion in scientific academic publications.

Double-blind peer review also arose in the 1960s, as a result of government grants, as this piece from Experimental History points out. It seems like a good idea, but it adds to the work we have to do as academics. Moreover, as the memes about “Reviewer 2” indicate, some reviews can be extremely unhelpful and in fact destructive, particularly to early career researchers.

Grant applications, as I have noted in a previous post, are very time-consuming and exhausting to complete and there is no guarantee of success. My partner was in scientific research, but he went into industry not long after completing his PhD, in part because of the need to apply for grants and “sell” the importance of his research.

As I have said before, I am a rara avis who does this job for the love it, but it’s hard at times not to feel like my cup has been emptied. I no longer apply for grants—I gave up in 2013, after it became evident that doctrinal private law scholarship is not favoured—but I am exhausted nonetheless by the demands of teaching, administration, peer review, and research.

Academia involves what author Will Storr calls a “status game”. In The Status Game: On Social Position and How Use It, he argues that are three ways in which humans gain status: through dominance (forcing others to respect our status by brute force), through virtue (convincing others that we are worthy by demonstrating belief or behaviour which serves the group interests, and decrying people who are not virtuous) and competence (being the best at something). His book made me realise that I am an end-product of Western status games of competence: “acclaim is earned by what you do, not who you are.” Who I am is irrelevant. I want to be judged by my output, regardless of who I am.

However, the status games of dominance and virtue still allow people to “win”. Indeed, the modern politics of social media is the ultimate global virtue game: it is vitally important is who I am, what my beliefs are, and whether they conform with the particular group’s morally virtuous views. As an aside, my views don’t tend to conform to anyone else’s wholly, and I am the world’s worst liar, so I tend not to do well at virtue games. In any authoritarian regime, left or right, I suspect I’d be first against the wall.

A friend, Lorenzo, pointed out to me that my desire for competence was all well and good, so far as it went. Being competent is an important part of being good at your job. But if organisations seek competence alone, without regard to ‘good character’, then you get a bunch of clever sociopaths at the top. He argues that some societies tested competence, but also set character tests, to exclude from office otherwise competent people who displayed the dark triad qualities (narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy).

With these strictures about competence, merit and character in mind, there are several assumptions I wish to question in this post:

That more publications are better.

That more citations are better.

That academics who publish are the only ones with “value”.

That academics can handle increased administration and bureaucratic demands without concomitant support.

I already admitted in a previous post that I publish a lot, so querying whether more is better could be seen as against my own interests, but I think it’s necessary. My Google Scholar page discloses that over half of my writings are not cited by other scholars. I sometimes wonder if I’m too prolific, and range over too many areas. No one can read it all.

If many scholars are publishing at the same rate as me: there’s an avalanche of material. How can anyone keep up with that volume? Moreover, emphasising the number of publications and citations alone encourages the less scrupulous to game the system.

In an academic legal context (the context I know best) citation by other scholars or courts does not necessarily mean that work has more value. In Jurists and Judges: An Essay on Influence, Neil Duxbury says at pgs 8–9:

The basic premise of citation analysis is that documents cited frequently are more likely to be influential than those which are cited less frequently, and therefore the impact of a particular document can be estimated by counting the number of occasions on which it has been cited. Citation, in short, might be treated as a proxy for influence.

As he goes on to note, this premise should be questioned. First, not all citations are the same. Ronald Coase produced the ‘most cited’ law review ever published, ‘The Problem of Social Cost’. For what it is worth, I have cited it several times. However, Coase himself observed in a follow up article, thirty six years later, ‘Many of the citations in the economics literature are in fact articles attacking my views’. I’d argue that this is still influential; I dream of creating that kind of a stir.

Secondly, an academic who is not cited may have influence (think of Albert Einstein). And those who are cited may be cited for reasons other than influence. Duxbury explains at pg 14:

To be popular is not necessarily to be influential and to be influential is not necessarily to be popular. Documents might sometimes be cited almost reflexively because they have acquired an iconic status; many of the citations to these documents will mirror not so much what the documents say as what they have come to represent.

The ‘Matthew effect’ can also mean that someone whose work happens to picked up is routinely cited, while an equally meritorious work which is not cited languishes. There is also the possibility that a clique of scholars all cite each other, thus consciously or unconsciously boosting each other’s signals.

I was astonished, when I became an academic, to learn that the main criterion for success was publication. Some colleagues were and are essential to the functioning of the law school—excellent teachers, and general all-round-good people—always there for you if you had a problem. They were, in many ways, a very important part of the ‘glue’ which holds our institution together.

But, despite protestations to the contrary, publication and research is the key to status in the academy, and if they did not excel at that too, then they were regarded as less important. If we lose these people from our organisation, we are all the poorer. The academy has need for excellent teachers, administrators, and mentors.

I worry that an unduly quantitative mechanistic measure of worth has taken over the academy, exacerbated by an obsession with ‘measurable outcomes’, and a burgeoning academic administration to measure and facilitate those outcomes.

We don’t need publishing machines alone. We also need people who teach and mentor and nurture others. We need people who will be the glue, people who have institutional memory, people who are more than just a number.

Someone quipped to me the other day that I was like a modern version of a 1930s Oxford don: slightly scatty, immersed in teaching, researching interesting things, and writing fiction. If only! I don’t think 1930s Oxford dons did their own administration. It made me think of this Tweet.

Unfortunately, in 2014, my university underwent a so-called “Business Improvement Program,” involving a “spill and fill”. Those who’d held administrative positions at the university had to reapply for their own position anew, often at a lower level of pay. Some positions were made entirely redundant. Along with several other colleagues, I stood against it at the time, and I believe strongly that we were right to do so.

In practice it meant that we lost years of institutional wisdom, that some loyal employees were totally crushed, that others went and found jobs elsewhere, and that those who remained out of loyalty were overworked and burned out. It was so entirely predictable. The echoes still resonate through our administration, six years later.

Good administrators are essential: they’re another part of the glue which holds our institution together.

Making academics do their own administration online, with no assistance other than a training video, is exhausting. I’ll confess that, while I’m good at research and teaching, I am a terrible administrator. Despite every effort, I have a tendency to reverse dates, to triple-book myself, or to end up in the wrong place altogether. (There is a reason why stereotypes of the absent-minded academic exist).

In any case, the “business improvement program” was a false economy. I now waste an immense amount of time wrangling with the university’s idiosyncratic and non-intuitive online forms, time which could be more usefully spent preparing for class, or researching, or writing.

I had to quit a university committee in 2021 after a particular online system associated with the committee drove me to tears. Someone said afterwards, “Did no one tell you that it always notifies you’ve made a fundamental error when you submit that particular form? You just have to press OK three times despite the warning message and exclamation mark in a triangle, and eventually the form will register.” It sounds like satire, but it isn’t. I’m sure academics at other institutions have similar tales.

So - what are the systemic problems? There’s the publish or perish problem, the lack of administrative support, the precarious position of sessional and junior academics, and the constant, soul-destroying demand to apply for grants which one may not even be awarded. Until these things are fixed, academics will continue to ‘quiet quit’, or quit altogether. And appreciation from one’s bosses, while pleasant, will not fix the deeper issue.

We need to find ways of funding universities which minimise these problems, but still allow us to teach and produce quality research.

An earlier version of this post said BIP occurred in 2017, but in fact it occurred in 2014. All the years have blurred together.

On administrators, genuinely helpful secretarial work is invaluable. That's not what we get in North America, however. Here it's massive administrative bloat, which ends up imposing additional bureaucratic time wasting nonsense on academics. To say nothing of the absolute cancer of the DIE regime, which is dug into admin like tics.

Speaking of DIE, certainly in my case this has had a fair bit to do with my own demoralization. It is one thing to work hard - research, publishing, reviewing papers, sitting on review committees, teaching, supervising, and all the rest. I built up a fairly impressive CV over the years. Then it came time to try and find a faculty position, just in time for the woke mind virus to completely take over the universities. So now I'm watching all of the available positions being taken by women and 'minorites', because admin have decided that new hires must 'reflect the world we live in today'. Buh-bye motivation, hello burnout.

The hyper-competitive grind is bad enough, in other words; when it's made clear that winners and losers will be selected on a fully arbitrary basis, that grind becomes intolerable.

Excellent.

You brought out something we have all forgotten--administration used to be in support of researchers, or executives, or academics. We called it "secretarial".

"In support of," not "rules over," as is now the case.