The playboy and the petroleum mogul

The hidden story behind a famous trust law case

Sometimes, people think private law or commercial law is boring. That’s not the case, because there are people behind any case, and people are always interesting. Today I’m going to tell you the hidden story behind a superficially dry trust law case, Re Gulbenkian’s Settlement Trusts,1 which established the “criterion certainty test” for ascertaining who benefits from a discretionary trust. Behind a badly-worded clause lies an unusual story of generosity and parsimony, threaded through by exile, two World Wars, the collapse of empires, and probably the most expensive dispute over a chicken lunch ever.

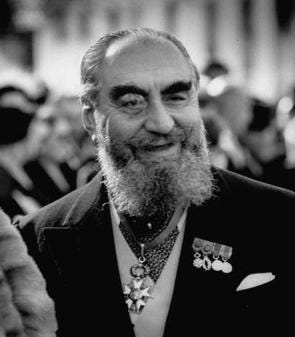

The two main figures in this case were a father, Calouste Sarkis Gulbenkian, and his son, Nubar Sarkis Gulbenkian. Calouste’s will contained a trust which had been initially intended to benefit Nubar, and a cast of other beneficiaries. However, Nubar himself was later cut out of the will, for reasons disclosed in his obituary in the New York Times:

The son worked for his father at no salary. One day in 1938, he wanted to have a working lunch. He had brought up to the office a light repast of chicken in tarragon jelly with asparagus tips, billing the $2.22 cost to petty cash. The elder Gulbenkian upbraided him for having charged the meal to the company.

The younger Gulbenkian was so infuriated that he sued his father for $10 million, an action he had been considering for some time to get what he considered his rightful share of a Gulbenkian subsidiary’s profits, which his father had refused to hand over. The case was finally settled out of court, but the father had to pay $86,000 in court costs and lawyers’ fees.

“That was surely the most expensive chicken in history,” Nubar Gulbenkian commented.

Why would a son be so infuriated by his father’s refusal to pay for chicken in tarragon jelly? The reason was simple. By the time of his death in 1955, Calouste was one of the world’s wealthiest individuals, with an estimated fortune between US$280 million and US$840 million. However, he was also famously miserly. According to his obituary in Time magazine, he died in Portugal, without his family around him:

During the last 13 years of his life. Gulbenkian lived in a drearily furnished suite of Lisbon’s posh little Hotel Aviz, voluntarily separated from his wife and family and the paintings which he sentimentally called “my children.” When an old friend pressed him to enliven the bare walls of his rooms with at least one painting, Gulbenkian replied in a rare moment of embitterment, “Do you honestly suppose that besides myself there are fifty men in the world who look at my collection other than through a mist of dollars?” Lost in the mist of millions himself, Gulbenkian fashioned an heir after his own heart, the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, which is preparing to house the art collection in Lisbon. On July 20, 1955, alone save for a nurse and secretary, Calouste Sarkis Gulbenkian, 86, kissed the last hand he could not bite—death’s.

Calouste was an Armenian petroleum engineer and oil magnate, born in the Ottoman Empire before its collapse. He was instrumental in the development of oilfields in the Middle East. His nickname was “Mr Five Percent”, because he insisted on retaining a 5% share of the oil companies he was involved with, and hence made his fortune. In the 1890s, he and his family had to flee the Ottoman Empire because of the Hamidian massacres, a precursor to the later Armenian genocide.2 Calouste and his wife hid their infant son Nubar in a Gladstone bag as they fled. They ran to England. He was the driving force behind the formation of the Turkish Petroleum Company (TPC) (later renamed the Iraq Petroleum Company) in 1912. When the Ottoman Empire broke up after World War I, the former Ottoman territory was divided up under an English and French mandate. Calouste was pivotal to the 1928 Red Line Agreement, where TPC allowed American, French and English oil companies to have access to Middle Eastern oil fields (of course, he kept a share of 5% of the deal).

In sharp contrast to his father, Nubar was determined to enjoy his own wealth as much as possible. He was educated at Harrow and Trinity College, Cambridge. He was independently wealthy through his own oil dealings. He was also a member of MI9 and helped British soldiers escape the Vichy French regime, as he was living in Paris at the time when the Nazis invaded.

Despite being cut out of his father’s will, he ultimately inherited $2.5 million from his father, and more in a settlement from the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation. His obituary in Time was very different to his father’s:

An impeccable dresser, he almost always wore a fresh orchid in his lapel; when visiting desert countries, he had the flowers shipped in daily. For a London party, he flew in a troupe of belly dancers from Turkey. Married three times and twice divorced, he remained childless. He had a superior attitude about good food and wine. The perfect number for dinner, he said, was two—himself and a headwaiter. In all he did, Gulbenkian remained a flamboyant refutation of the notion that the burden of having money dims the joy of living.

He was known to be highly eccentric.

As Nubar’s obituary in New York Times noted, he was also a well-known playboy:

Even in his youth, Mr. Gulbenkian had a flair for making money and finding pleasure in life’s delights. At Cambridge, a friend, George Ansley, said of him:

“Nubar is so tough that every day he tires out three stock brokers, three horses and three women.”

Mr. Gulbenkian approached the subject of women with gusto, and he spent a breezily gay life chasing chorus girls. Finally, however, he settled down to marriage—three times. He could be quite philosophical about what he called his “marital follies.”

“I've had good wives, as wives go,” he remarked, “and as wives go, two of them went.”

It’s understandable, in light of this, why Calouste was worried that the son would fritter away his money. However, Nubar’s decision to become a bon vivant is also understandable: he was going to enjoy his life and his money as his father had not.

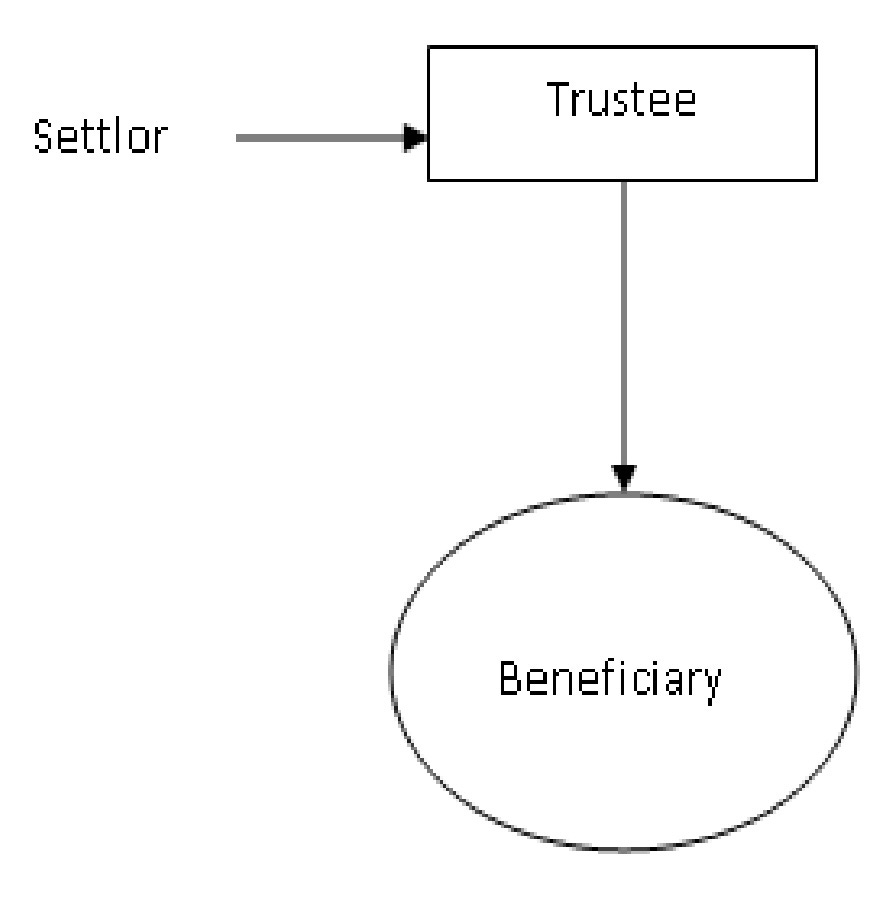

How, then did this will end up in court? The will contained a “mere power” of appointment (a kind of discretionary power on the part of the trustee to pay the beneficiaries). This is in contrast to a “fixed trust”, where beneficiaries of the trust are generally listed, as are the proportions they are entitled to. The trustee has no discretion: he or she must give the property to the beneficiaries on the terms stipulated.

Discretionary trusts, on the other hand, give the trustee discretion as to whom they can distribute assets to,3 and even whether to distribute assets at all.4 At first, even for discretionary trusts, it was necessary to have “list certainty”: to be able to draw up a list of who was entitled to receive trust property. This meant discretionary trusts such as pension trusts failed, because it was impossible to draw up a list of all the beneficiaries.5 Re Gulbenkian was the first step towards the loosening of the rules regarding discretionary trusts. The question of who is entitled to trust assets matters for trustees because they must distribute assets according to the terms of the trust, and they can be liable for misapplication of trust funds if they get it wrong.

Lord Upjohn notes in passing that the clause in Calouste’s will seems to have intended to be a “spendthrift” clause,6 in keeping with his general concern to control his son’s access to money. “Spendthrift” clauses are intended to prevent the beneficiary—or creditors of the beneficiary—from accessing trust assets. The beneficiary has no definite entitlement to the money, because his entitlement depends upon the trustees’ discretion, and therefore for the purposes of creditors, the beneficiary does not own anything at all. But the trustee has to be able to ascertain who is entitled to the assets for this to work.

This clause was very difficult to understand. The trustees were to “pay all or any part of the income of the property” on Calouste’s death:

for the maintenance and personal support or benefit of all or any one or more to the exclusion of the other or others of the following persons, namely, the said Nubar Sarkis Gulbenkian and any wife and his children or remoter issue for the time being in existence whether minors or adults and any person or persons in whose house or apartments or in whose company or under whose care or control or by or with whom the said Nubar Sarkis Gulbenkian may from time to time be employed or residing and the other person or persons other than the settler [sic] for the time being entitled or interested whether absolutely, contingently or otherwise to or in the trust fund under the trusts herein contained to take effect after the death of the said Nubar Sarkis Gulbenkian in such proportions and manner as the trustees shall in their absolute discretion at any time or times think proper.

Whew. Can you work out to whom the trustees can give money? It starts out clearly enough. There’s Nubar, his wife and children and other remoter issue. And as we know, Nubar gets cut out later. But after that, it gets tricky. Lord Reid says:

I think that it is reasonably clear that this clause is the result of carelessly telescoping two separate clauses - (1) any person by whom Mr. [Nubar] Gulbenkian may from time to time be employed, and (2) any person in whose house or in whose company or under whose care or with whom he may from time to time be residing.7

It is easy enough to establish if a particular person has employed Nubar, but as Lord Reid goes on to note, the second criterion provides a little more difficulty.

At first instance, the trial judge found the clause was too uncertain, but the Court of Appeal said that as long as one person could be found who fulfilled the criteria, that was sufficiently certain.8 The House of Lords overturned the Court of Appeal, and said that it was necessary to have a criterion according to which you could definitively say whether a given person fulfilled it or not. This became known as the “criterion certainty test” and this test is still applied to mere powers (clauses where there is absolute discretion).

For some reason, Lord Upjohn’s discussion regarding hypothetical clauses that might fail this test has always made me laugh. He first raises the prospect of a case where the trust requires the trustee to distribute to “John Smith”, but the settlor of the trust knows three men named John Smith. Unless there’s evidence to show which John Smith was intended, the gift will fail. Then he gives the example of a trust for “my old friends”. Again, unless the settlor has a specific meaning for who “my old friends” are, it’s impossible to say whether someone is or is not an old friend. Such a clause would also fail.9 Although the examples seem ridiculous, the mere power in Re Gulbenkian is also extraordinary.

In this instance, the court struggled, but decided that ultimately the intention behind the clause could be ascertained, and just because it was difficult to interpret, the trust did not fail. Meanwhile, Calouste chose to use much his millions to create a foundation for the arts in Portugal, as he’d been a very keen art collector during his life.

Little would he have realised that the vexed relationship between him and his son would cause his name to become synonymous with fundamental principles of English (and Australian) trust law.

[1970] AC 508.

As an aside, this is unfortunately yet another example of commercially successful minorities being targeted for their success, along with Chinese merchants in South East Asia and Jews in Europe.

A “trust power”: the trustee must distribute to the beneficiaries, but has discretion as to how to distribute according to the criteria of the trust.

A “mere power”: the trustee has a discretion whether to distribute to the beneficiaries according to the criteria of the trust.

It is no coincidence that the next case to come up to the House of Lords was McPhail v Doulton [1971] AC 424 concerning a trust to benefit any employees and officers, or any ex-employees and ex-officers or any relatives or dependents of any such persons which the trustees could distribute in such amounts at such times and upon such conditions as they thought fit.

Re Gulbenkian [1970] AC 508, 522.

Re Gulbenkian [1970] AC 508, 517.

Re Gulbenkian [1968] Ch 126.

Re Gulbenkian [1970] AC 508, 523 - 24.

That was fun. Any recent perpetuity follies?

the fayed cases as well - always funny when famous people cameo in cases