Testing what matters

A comparative analysis of a martial arts drama and Ivy League Presidents

I recently watched another Chinese drama, a wǔxiá called Blood of Youth. I enjoyed it immensely. It follows the adventures of two young men who are establishing themselves in the martial arts world, Lei Wujie (Ao Rui Peng) and Xiao Se (Li Hong Yi).

After I’d finished the series, it struck me that there were parallels between the fictitious martial arts world of the show, and academia. In Blood of Youth, levels of expertise in martial art are reached by cultivation of one’s skills (practice), listening to the teachings of experts, and innate talent. Eventually, an expert martial artist becomes a “deity”. The “deities” are not necessarily good or wise, for all that they have great skill and power. The parallel with the professor who reaches “legendary” status is irresistible.

Teaching and learning are central to the series. This is unsurprising. Confucius, the Chinese sage, conceived of the teacher-student relationship as pivotally important to society, a mutual and life-long bond, where both student and teacher learned from one another.

There is, of course, a competitive aspect to the martial arts world, just as in academia. The characters strive to be the best. At some points, they could obtain immense power and status, but at the expense of their friendships and principles.

In one scene, Xiao Se has an opportunity to obtain a magic weapon of unimaginable power. Once he has reached the sanctum where it is kept—something few others have managed—he endures trials. The first is to confront his inner demon: in his case, his difficult relationship with his father. The second is to put the interests of the community above the life of his friends and colleagues. He then discovers that in reality, his beloved friend has been badly wounded while protecting him, as he has advanced through the trials. Is the magic weapon worth the effort, if it requires him to both figuratively and literally sacrifice his friends and colleagues?

I’m not going to spoil the story, but it made me think of academia. If you want to rise higher in the ranks of a university, to what extent are you required to make choices like Xiao Se’s? Must you put aside your principles for the interests of the greater community? I am not built to sacrifice my friends. I simply don’t have the requisite level of moral certitude to sacrifice those I love for the greater good. I don’t think I ever will.

At the same time as watching this drama, I saw another unfold: the Presidents of various Ivy League universities testifying before Congress. While I may lack the moral certitude to sacrifice my friends, I'm entirely certain that calling for the genocide of any ethnic or religious group on a university campus is morally contemptible. This is particularly so where the group in question has, in fact, suffered genocide within the last hundred years. I would have had no difficulty answering those questions unequivocally.

I wondered whether those Presidents (and those who advised them) realised how this looked to people outside the university environment. I suspect they’d rarely been outside the bubble of the academic world.

Frankly, my shame would make me want to fall on my sword, were I them. Liz Magill of Penn stood down shortly after the testimony. Today, sensationally, after a month under fire, Claudine Gay of Harvard has resigned. Sally Kornbluth is still in office.

This is not the only controversy to have arisen as result of the testimonies. The quality of the scholarly work of Gay came under question. Kornbluth’s work, however, remains unquestioned.

As the WSJ recently reported, Gay is a polarising figure. Some say that she receives adverse attention because she is an African American woman; others say that it is only because of her identity that she has been able to deflect questions about her work, politics, and management style. Until I saw her give testimony before Congress, I had no preconceptions about her whatsoever, although I thought her name was vaguely familiar.1 I had never heard of Kornbluth before.

In the day or two after her testimony, some noted that Gay has not published many papers during her career: only 11, albeit in top journals. Her research centres on race and identity, and its impact on political behaviour, from a social justice perspective. By comparison, a selective bibliography of Kornbluth’s work lists over 120 publications. Her research considers apoptosis (programmed cell death) and how this impacts upon replication of cancerous cells, and upon female fertility in vertebrates.

It might be argued that the difference in number of publications reflects different author attribution practices in sciences and arts. In arts and humanities, we do not tend to be listed as co-authors as readily, and therefore we have fewer publications.

However, I am in a more humanities focused area. All but two of my publications date from 2007 onwards. I have published one monograph, one treatise, one co-authored textbook (about to be released in its third edition), one co-authored casebook (first edition), one co-authored non-fiction legal book, and one co-authored treatise, as well as 19 journal articles (3 co-authored), 8 case notes, 17 book chapters (2 co-authored), 3 book reviews, 3 other publications and 20 scholarly blog posts.

I am not saying this to boast, I promise. I am simply trying to illustrate why I was at first surprised by Gay’s publication record. However, the quantity of publications is not an indicator of the quality of her work per se, nor does it mean she’s a bad academic. Quantity does not always mean quality.

And, while I am a prodigious author, both Gay and Kornbluth have a higher h-index than me. Google scholar gives me 7, Gay 11 and Kornbluth 66. In other words, I write a lot, but I’m not cited much by other scholars, even though I have received very positive reviews of my work, and I am frequently asked to contribute to conferences and collections. I will confess that, sometimes, I have felt insecure and bitter about this. There was a moment in 2018 where I wondered if I was wasting my time by producing so much.

I’ve decided I’m not wasting my time. I hone and clarify my ideas by writing. That’s helpful for my teaching. Moreover, legal practitioners and judges have said my works are useful, and I have been cited by top courts. The relevant measures of one’s work in commercial law are being useful in practice, and being cited by courts. Citation by a superior court is more important to black letter law academics than an h-index: it means you contribute to the law. I should be content.

I’ve also made choices which have contributed to my citation count. In Blood of Youth, the martial artists congregate in sects or clans, most quite large, but there are a few in small sects. Extending the analogy, I don’t belong to a large “sect”, where other members might cite me to advance the sect’s general thesis. If citation was what I wanted, I should have signed up to a large and influential “sect” and followed the precepts of an eminent “deity” at the outset of my career. However, I know myself. I’m sure that—even had I been able to accept the majority of the sect’s tenets in the first place—I would have been expelled for questioning them.

Much better to mosey around, talking to everyone, using bits of their work I like, learning from them, and building my own path, gathering kindred spirits along the way.

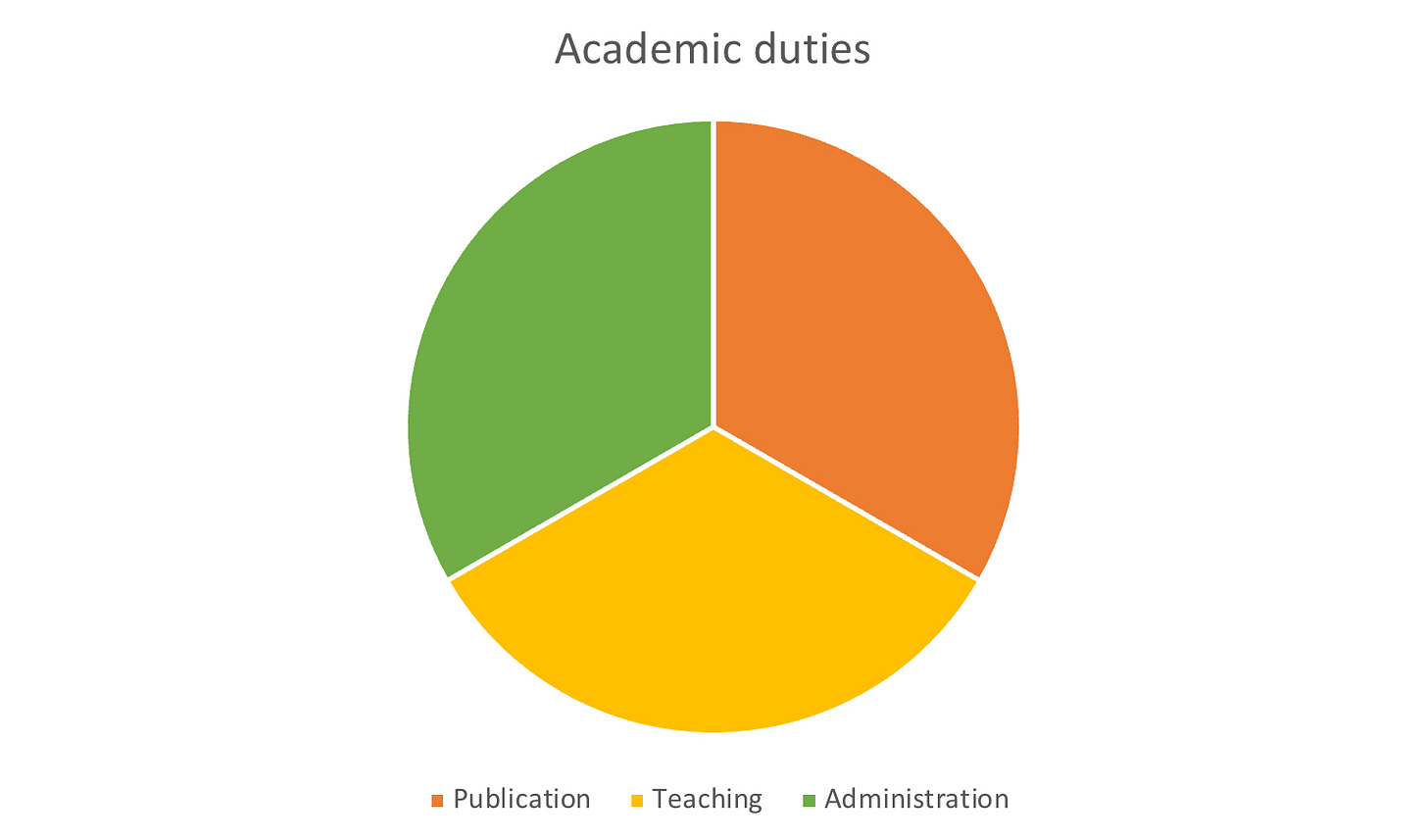

It’s taken me a while to process my thoughts on the broader allegations levelled at Gay. I came up with a pie chart of the skills an academic must have.

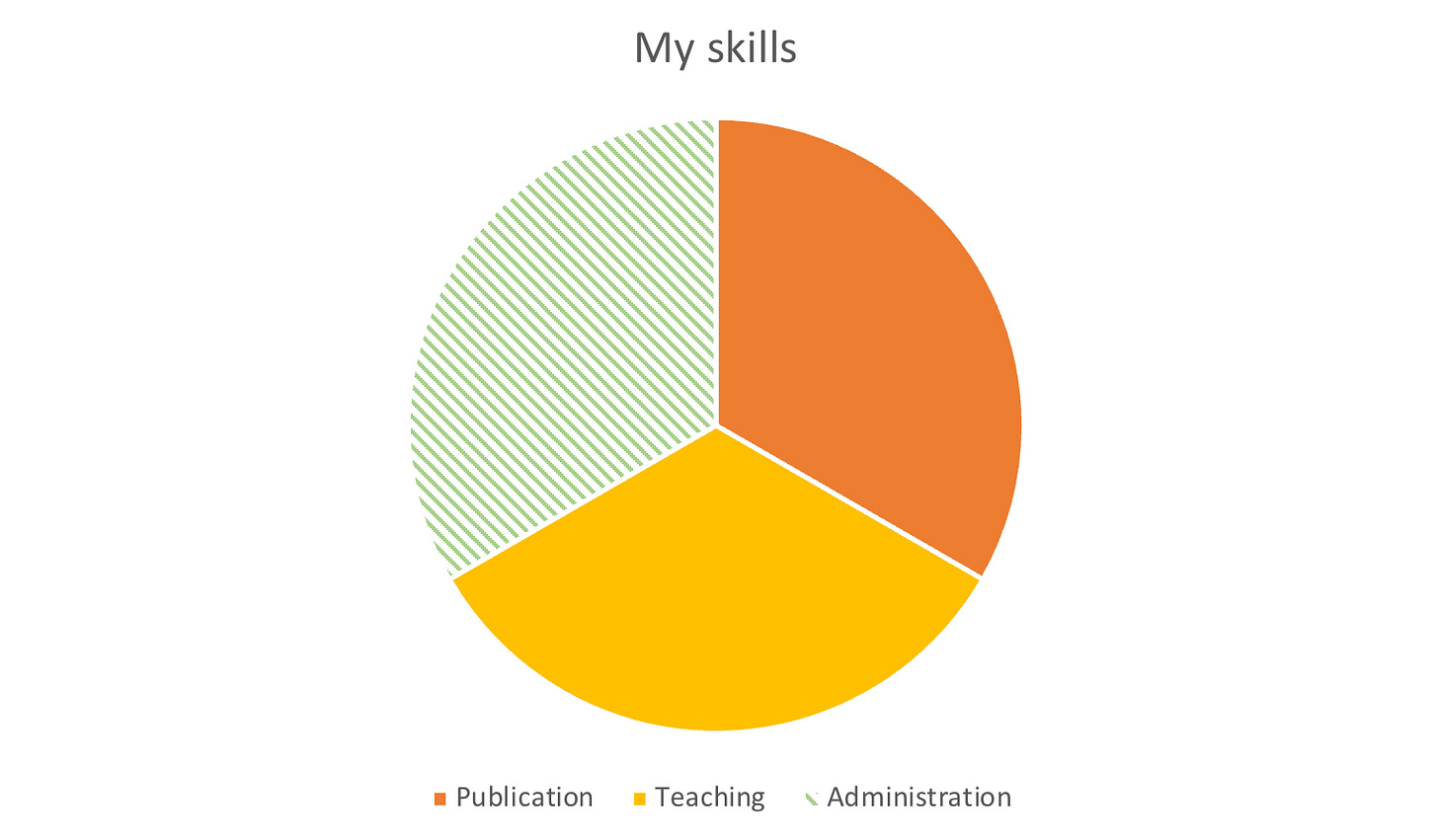

An honest pie chart of my own skills looks like this:

The hatching of the green section represents the reality that while I have leadership qualities—I will stand up for colleagues or students without fear or favour when necessary—I am not very good at administration, especially navigating meetings, forms, and bureaucracy. I do not like to admit this, because I like to be competent at all I do. However, I must face it. I have severe issues with dates, times and scheduling, which I find utterly humiliating. I have to put in an immense amount of effort to ensure I don’t stuff people around (including myself) but sometimes, it still happens.

I know of other academics whose pie charts might look like this:

The orange hatched section indicates that publication is not their strength. They do not publish much, and not necessarily in top journals, but they are excellent teachers and administrators. In fact, in my experience, such academics are the backbone of the university: the “glue people” who make everything work for both students and staff. The academy’s current emphasis on “publish or perish” as a measure of quality means that they may be overlooked, and the academy is therefore a poorer place. We really need these people.

I have noted elsewhere that I think “publish or perish” is a scourge. I publish so much simply because I think by writing, and I like to share my thoughts with students and colleagues. I am very reluctant to damn someone on the basis that they do not publish much. It does not necessarily mean that they lack value as a colleague; sometimes, quite the opposite.

There’s an important difference between the fictitious martial arts world and the academic world. The martial arts world is subject to constant reality tests. You can readily gauge skill, and any mistakes have immediate physical consequences, up to and including death. Conversely, generally, the ramifications of one’s choices in academia do not result in immediate physical injury. You don’t see your friend sprawled on the path, semi-conscious and bleeding.

When a skilled sword “deity” loses capacity and cultivation, it is immediately evident, and that person must withdraw from duels. Of course, there are cheats in Blood of Youth too: warriors who use trickery or poison or unfair ambush. There are always people who will cheat the system. But there’s no way someone can pretend to have a skill he or she does not possess. There’s also no doubt that the “deities” actually possess immense and unparalleled skill, even if they use it unwisely or act in stupid ways.

In academia, it’s more difficult. Our status as academics is often measured by how much we publish, and what other academics say about of our work, including peer reviewers, journal editors, academic colleagues, and academics and others who cite our work. These are the reality tests we put in place to ensure the quality of our work.

Sometimes, however, these tests fail: someone has rigged experiments; falsified data; plagiarised work; used junior students to do their work; used their position to exclude scholarship which is soundly based, because they disagree with it; or simply been negligent. The allegations levelled against Gay concern plagiarism.

Of course, all scholarship is derived from the work of others. My work is based on that of generations of lawyers, judges and academics before me. In European medieval scholarship, as I noted in my piece on Tolkien and King Arthur last week, it was fine to shoehorn chunks of other people’s writing into your own work without attribution. That’s not acceptable by today’s rules.

Conservative investigative journalistChristopher Brunet quit his day job last year to continue reporting on Gay, after receiving anonymous tips regarding plagiarism in her work. Recently, in collaboration with Christopher F. Rufo, he analysed Gay’s PhD—for which she was awarded Harvard’s 1998 Toppan Prize for the best dissertation in political science—and noted that it closely paraphrased the work of others. References had been given for most (but not all) of the relevant pieces which had been paraphrased. I hadn’t heard of Rufo before; he is apparently a prominent US anti-woke activist. Interestingly, as the WSJ relates, the New York Post had wanted to run a story on Gay and plagiarism too, but had desisted after Harvard threatened it with a defamation suit.

If I discovered that a student had done something similar to the allegations regarding Gay’s PhD citation practices, she would likely get an “educative response” at first, namely, an informal but serious warning. The student would be advised that it is better to rewrite paragraphs in your own words, and warned that it would be unwise to do it again, and that more serious ramifications might occur next time.

Given the way in which I’d treat a student, I was not so surprised to hear that after an internal review, Harvard decided that Gay’s PhD citation practices were inadequate, but “while regrettable, did not constitute research misconduct.” She amended her PhD. The controversy did not end there, however. Further allegations of plagiarism have now arisen in relation to some of Gay’s other publications, including more uncredited paraphrasing. Moreover, Brunet has also alleged that Gay has refused to share the datasets for some of her statistical work.

I can’t speak for others, but when I produced my sole statistical article, I offered to provide my full data set, and the method I used, to anyone who wanted it. I personally believe transparency demands it. And I want people to find any mistakes in my analysis, if there are any.

Some argue that problems with Gay’s work were overlooked or brushed under the carpet because Harvard thought it was more important to signal that it was an organisation which promoted diversity, equity and inclusion. Others such as Arnold Kling see her appointment as a symptom of a deeper systemic problem, and argue that even when she goes, the problem subsists. The irony is, of course, that the “brand” of the Ivy Leagues subsists on exclusivity, not inclusivity.

After questions were raised about Gay’s research, I wondered whether she was perhaps an academic whose strengths lay in teaching and administration. We all have different skill sets.

I assume Gay has not done much (or any) teaching since 2015, when she was appointed as the Dean of Social Studies at the Harvard Faculty of Arts and Sciences (FAS), and absolutely none since she was appointed President of Harvard University in July 2023.

Interestingly, her CV (not updated since 2012) mentions her publications but does not mention her teaching. She may be an excellent teacher. I can’t judge from what she says about herself. Conversely, Kornbluth has won a research mentoring award, so this prima facie indicates that she is good at training early career researchers.

I compared my own CV with Gay’s. My prize for teaching, a list of the numerous subjects I have taught, and the teaching seminars I’ve given to the university take up over a half a page. I have placed teaching above my academic publications, something I only realised when undertaking this exercise. This indicates the importance I place upon it.

Gay’s 2012 CV discloses that she has undertaken extensive leadership and administrative service at the universities at which she has worked, far greater than mine (as per my earlier confession). Kornbluth has a similar trajectory, after she moved out of research and into administration in 2014.

If we went solely off Gay’s and Kornbluth’s CVs, their pie charts would have a solid green slice. It’s surprising, therefore, that neither did a better job of defending her university.

I wonder whether Kornbluth in particular, as a Jewish academic, was hamstrung by her office, and felt compelled to express the “institutional position”. This is another reason why I am not an administrator. If the institutional position conflicted fundamentally with my principles, I could not readily espouse it.

I read a translation of the Analects of Confucius to write this post (as one does… well I do). I was struck by this passage in Ch 13:

The Master said, “Though a man may be able to recite the three hundred odes, yet if, when intrusted [sic] with a governmental charge, he knows not how to act, or if, when sent to any quarter on a mission, he cannot give his replies unassisted, notwithstanding the extent of his learning, of what practical use is it?”

All three Ivy League Presidents—Magill, Kornbluth, and Gay—faced a reality test of their administrative and leadership skills when they gave their testimony before Congress. All were resoundingly drubbed, in front of millions, when it became evident that some students are protected from harassment; others are not, and free speech will be trotted out to excuse the latter behaviour. The use of free speech was cynical and hypocritical, given the Ivy League universities’ signal failures to uphold free speech in many other respects.

They knew not how to act, and could not give their replies unassisted. It was clear that the Presidents had been cribbed by university legal advisors and others in their responses. Therefore, regardless of the quality of their scholarship, or their teaching, we might be tempted to conclude that their learning was not of practical use here.

What are we to make of all this? I’m not sure yet, but I am thinking of a scene from Blood of Youth (crossing over Episodes 16 and 17) where Lei Wujie is upset by bad behaviour in the martial arts world.2

Lei Wujie (LW): “But this is wrong! This fighting will create hatred among people and it will never end! This is not the martial arts world I want!”

Xiao Se (XS): “I know. You want a peaceful world where you can enjoy life.”

LW: “Am I being simple-minded?”

XS: “Do you know what kind of martial arts world lies within my heart? [pause] I once thought the martial arts world was like the imperial court. There was only unlimited ambition. That was, until I met you [and other characters and clans]. Now I think the martial arts world is like a mirror.”

LW: “A mirror?”

XS: “When we stand before a mirror we can see ourselves. When we face the martial arts world, what we see is our hearts.”

LW: “You mean… we see what we want to see?”

XS: “Yes. Your heart wants to be in the martial arts world. If your heart is full of resentment and darkness, then you’ll think the martial arts world is ruthless. But if your heart sees hope and brightness, then you’ll become more enlightened. So remember, no matter what happens, don’t forget what you were like when you first entered the martial arts world. That is your true self. Your [relative] says that you lack a killer’s heart, but that’s exactly your most invaluable trait. …

LW: “I understand.”

Perhaps academia is a mirror too.

I could have continued in commercial practice. Instead, I went into academia. I had a desire to teach, to make complex issues clear, to have conversations and debates, to learn and seek the truth, to exercise my extensive intellectual curiosity, and to tell people interesting things. Like Lei Wujie, I also want a peaceful world where I can enjoy life. At first, I thought everyone had similar priorities to me. Then, I realised that some people were motivated by other aims.

The current world of academia is not the world I want.

I have to remember why I joined the world of academia. I do wonder what Magill, Kornbluth and Gay would see, if they looked in the mirror?

I now think that I might have heard Gay’s name in connection with Harvard’s decision to make Ronald S. Sullivan, an African American law professor, stand down from his position after he agreed to defend Hervey Weinstein. As I said at the time, as a lawyer, I think the decision to stand Sullivan down was deeply wrong according to the rule of law.

Translation from Viki version of the show, with a couple of edits to make the English more idiomatic.

I know of someone who publishes several articles per year in law. This person is currently a PhD student and continues to publish quite incessantly. I noticed that they always co author. I have suspicions that undergrad level student work is being converted to journal articles in exchange of coauthorship. It made me wonder to what extent have we gone that ECRs are also trying to shore up their numbers by possibly exploiting someone below the chain. To people who produce several articles per year - how is your innovative ? One cannot just keep producing ideas out of thin air especially in Law where everything moves slowly.

Maybe I missed it, but yours seems like a level head, so maybe you can point me in the right direction. What exactly was so abhorrent about their responses that it would merit irreconcilable shame? The questions themselves were incendiary and their parameters were absurd. Free speech is a tricky topic and boundary between freedom of speech and harassment is indeed context dependent. They repeatedly said this, and when pressed for the "right" answer they gave variations of this. For some "From the river to sea" is a call for genocide, is this speech prohibited? The entire inquisition-sorry, hearing- was done in terrible faith and its hard to take any of it seriously. Sure, one may fault the presidents for not handling the absurd questions more expertly. How did this inform better freedom of speech policies? What did we learn, except that circuses are a favorite and effective tool of the political arm?