Unsafe spaces

Freedom of debate and universities

It’s been an interesting week to be an academic. The Presidents of Harvard, the University of Pennsylvania (Penn) and Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) have been grilled before a US Committee of the House of Representatives for their failure to prevent antisemitism on campus. None of the respective Presidents— Claudine Gay, Liz Magill and Sally Kornbluth—could give a straight answer on whether calling for “genocide of Jews” would violate their respective university codes of conduct on bullying or harassment.

Unsurprisingly, there were calls for all three Presidents to resign in the wake of their testimony, and Magill has since voluntarily resigned, as has the Chair of the Board of Trustees at Penn, Scott Bok. The Republican-led House Committee on Education and the Workforce has decided to investigate learning environments and disciplinary policies at these universities, and will possibly extend the investigation to other universities.

One may question how—in an age where being accused of being a Nazi is one of the worst slurs one could imagine—it became acceptable to openly call for the genocide of Jews on university campuses.

The answer lies in postcolonial theory, familiar from my undergraduate arts degree. To get a sense of this scholarship, let me quote Frantz Fanon, the original postcolonial scholar:

The naked truth of decolonization evokes for us the searing bullets and bloodstained knives which emanate from it. For if the last shall be first, this will only come to pass after a murderous and decisive struggle between the two protagonists. That affirmed intention to place the last at the head of things, and to make them climb at a pace (too quickly, some say) the well-known steps which characterize an organized society, can only triumph if we use all means to turn the scale, including, of course, that of violence.1

Fanon argues that it is acceptable to kill or use violence under an ethno-nationalist banner, but only as long as you’re oppressed by a capitalist Western coloniser. Indeed, although he was from Martinique originally, Fanon fought for the Algerian National Liberation Front during the Algerian War of Independence from France.

Of course, as Lorenzo Warby has pointed out, Fanon’s analysis overlooks the fact that the African slave trade was first established by Africans and Arab Muslims, not the West, and that the Arabic word for Sub-Saharan Africans was abd, meaning ‘slave’. Fanon himself was descended from Afro-Caribbean slaves. Both the Atlantic and Islamic slave trades were still operative at the time when the French conquered Algeria.

Moreover, the famous sociologist, historiographer and philosopher Ibn Khaldun used the rise and fall of successive conquering dynasties in the Maghreb to illustrate his theory of why empires rise and fall. The Muqqadimah is a work of great brilliance and remains cogent to the current day. As a medievalist, I’m always baffled by the proposition that only Western nations and empires engage in imperialism and colonialism. Isn’t it Eurocentric to ignore the annexation of lands by conquering dynasties of a non-Western origin? I suppose it doesn’t fit a simplistic rubric such as Fanon’s, where the only colonisers are Western oppressors.

It follows that, if one accepts Fanon’s rubric, calls for the extermination of Israelis are morally justifiable because they are citizens of a settler-colonial state, and as ‘Western’ ‘white’ oppressors, they—and any persons who support them—must be violently resisted.2 This petition condemning our Vice Chancellor’s statement on the Israel-Gaza conflict reflects the tenor of these arguments.

As an aside, the drafter of the 2017 Hamas Charter has evidently read postcolonial scholars, and utilised these works cleverly. The revised charter plugs directly into postcolonial narratives, in distinct contrast to the earlier 1988 Charter, which had a strong Islamist flavour. Hence in Art 14 of the 2017 Charter, it is stated:

“The Zionist project is a racist, aggressive, colonial and expansionist project based on seizing the properties of others; it is hostile to the Palestinian people and to their aspiration for freedom, liberation, return and self-determination.”

Similarly in Art 17, it is stated:

Hamas is of the view that the Jewish problem, anti-Semitism and the persecution of the Jews are phenomena fundamentally linked to European history and not to the history of the Arabs and the Muslims or to their heritage. The Zionist movement, which was able with the help of Western powers to occupy Palestine, is the most dangerous form of settlement occupation which has already disappeared from much of the world and must disappear from Palestine.

According to the 2017 Charter, all problems in the Middle East arose only as a result of Western antisemitism and colonialism.

Anyone with the slightest knowledge of the complexities of Middle Eastern history knows that such a proposition should be taken with a grain of salt. Certainly, colonial powers have contributed to the current conflict—British Mandate, anyone?—but the reality is far more complex, just as the history of how Fanon’s ancestors were enslaved was far more complex than he was prepared to acknowledge.

I believe that my Vice Chancellor’s statement on the Israel-Gaza conflict was principled, and I salute him for it. It is not for an educational institution to take sides in a war outside Australia.3 It is appropriate to express regret for all students and staff who’ve had family members or friends killed, maimed, or displaced as a result of this conflict. As a university, we represent a diverse body of students and staff, and owe a duty of care to them all.

The problem is broader than the Israel-Gaza dispute. There have been times, in the last year, when I have felt that it was dangerous to ask questions or express views. I have even felt a genuine fear for my safety. I never thought this would happen in Australia.

Recently, I’ve seen academics embroiled in controversy, sometimes wittingly, but more often unwittingly. In several instances, academics have been told that they should stay off campus, to avoid vocal or even violent protest, simply because they said (in good faith) that an issue was “complex” or that there might be another side to the story. Some felt compelled to teach online, or to consider whether it would be safer to teach online.

I was told that I should be wary of voicing “controversial” opinions in the current fervid climate because I might face protests, and my physical safety might be at risk. This is why I was so pleased when our Vice Chancellor stood up against violent protesters.

While the Ivy League Presidents’ answers to the Committee technically reflected US free speech jurisprudence, the responses came across as hypocritical because these universities have failed to apply the same standards across the board to all speech. I couldn’t help thinking of George Orwell’s Animal Farm: “All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others.”

Frankly, their testimony struck me as unprincipled. I hope that the ensuing backlash acts as a reality check on university administrators globally. Intimidation, incitement to violence, and actual violence are beyond the pale, as a matter of principle. You can’t pick and choose who to protect on the basis of whether you find them politically palatable.

A safe space at a university is a place where you can safely ask questions and express differing views, in good faith, without fear that your career will be destroyed, you will be punished, or physically attacked.

We cannot demand that people accept or affirm our views. We can only ask people to tolerate them.

Students and staff should be able to have civil disagreements without others demanding that everyone must accept all aspects of their point of view. There are times when, ultimately, all you can do is agree to disagree. C’est la vie.

As I tell my students, I ask questions. I don’t mean to offend—I try to ensure that my questions are in good faith—but I rub people up the wrong way sometimes. And, of course, sometimes people rub me up the wrong way. We are all but human. However, I have sometimes learned greatly from difficult and uncomfortable questions.

When a scholar completes a PhD, he or she is subjected to a viva, an oral defence of the work, where a panel of experienced scholars ask questions. I had always thought that the purpose of this was to ensure that the work is of sufficient quality. It struck me recently, however, that it may have another purpose. It may be designed to weed out those scholars who are unable to handle people questioning their work. Questioning is—or should be—intrinsic to the academic mission.

I believe that questioning aids learning and discovery, and that it is integral to the academic mission. I have learned so much from my students’ questions. I would hate it if my students felt unable to ask me questions because they were scared I’d judge them or discriminate against them.

I also believe in freedom of speech and academic freedom. As long as academics do not incite violence, intimidate and threaten those who disagree with them, or commit wrongs such as defamation, they are entitled to express views which I find offensive or believe are downright wrong.

The corollary, however, is that I must be able to disagree, and I must believe that both my employer and my union will back me. I left the NTEU because I no longer felt confident that I would be backed, given the highly partisan statements made by my local Union branch. Moreover, I’d heard that the local branch had refused to help at least one union member whom they regarded as ‘problematic’.

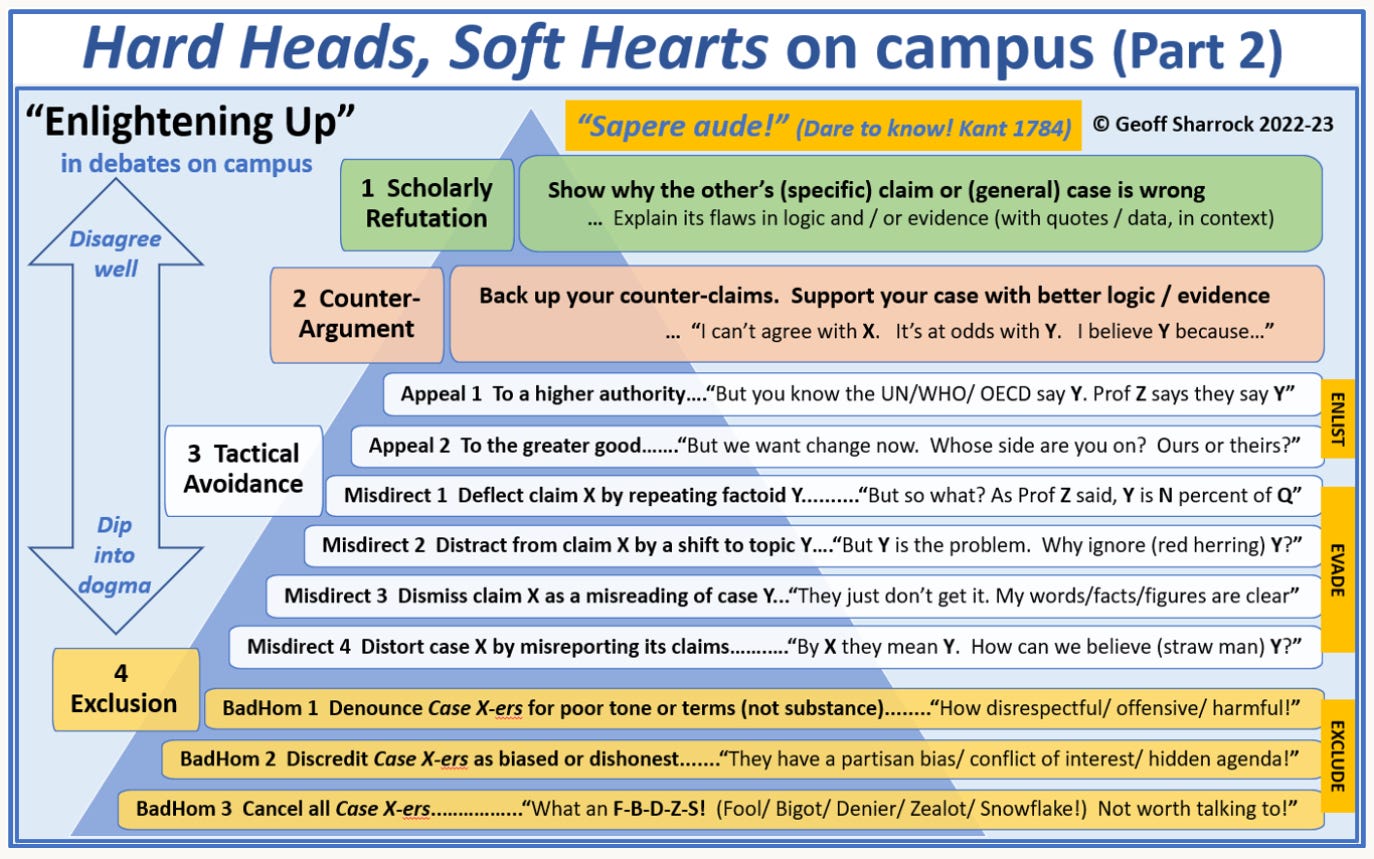

Many people across the political spectrum seem to have forgotten how to engage in reasoned argument, and not just in academia. They say on social media, “This is a bad take”, and accuse the person who expressed the view of being immoral and throw insults in their direction (Nazi, fascist, racist, libtard, woke, snowflake, idiotic, stupid, liar). Then they wait for their “tribe” to like their “argument” and pile on the objectionable person. This is not a good way in which to engage in reasoned scholarly argument, as Geoff Sharrock illustrates with this excellent table—I commend his work, yet again.

Some scholars agree entirely with the ad hominem attack, and feel a happy glow that they are on the side of righteousness. Others may publicly agree, or say nothing about their doubts, simply because they don’t want to be placed on the outer.

Please note, the latter reaction is quite rational. A recent study showed that 38% of participants in an experiment by Swiss scientists were likely to change their view and agree with a political proposition when others in a group said that the proposition was correct, in a variation upon Asch’s experiment.4 It reflects Damian Counsell’s Second Law:

The two most powerful forces known to contemporary humankind are peer pressure and the desire for a quiet life.

Again and again, I’ve caught myself saying, “I’ll just keep quiet. No one needs to know what I think. I’ll just talk to close friends, and not alienate people. I’ll stop asking questions.”

If I cannot ask questions, I cease to be myself.

It is fair to ask that, in argument, people do not incite violence, or threaten people, and to ensure that they do not commit legal wrongs. It is also fair to ask that people are tolerant, and ask them to recognise that there are diverse beliefs and backgrounds among university staff and students.

Questions in good faith are the core of learning and academic discourse.

It seems to me that some of this is about humility, specifically, the humility to be able to accept that, no matter how clever or correct we like to think we are, what we see as an incontrovertible truth may in fact be a contestable and contested proposition. The world isn’t as certain as we thought it was. That’s a humbling thought.

Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth, Constance Farrington (trans.) Grove Weidenfeld, pg 36.

Never mind that a substantial proportion of Israeli Jews are descended from refugees from Muslim countries.

For what it’s worth, I am on record as saying that I don’t think the University should have taken official positions on other political matters either. Individual staff can take a position, of course, but the institution should not.

Franzen A, Mader S (2023) The power of social influence: A replication and extension of the Asch experiment. PLoS ONE 18(11): e0294325. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0294325

Well said Katy! I watched at least part of the testimony of these three university presidents and found it cringeworthy. Yes, perhaps they were struggling under the stress, but isn’t it part of their job to speak on behalf of the university leadership, and to answer difficult questions? Yes, the questions from the Congress members were tough, and sometimes aggressive, but the presidents’ answers lacked moral clarity. For example, claiming that the acceptability of calls for the genocide of Jews depends on the context implies that there are contexts where such calls could be justified. Obviously, there are no such contexts. Also, claiming that such speech should not be disciplined unless it translates into conduct (meaning actually committing genocide?) is preposterous. I can see why the Congress members became angry.

I'm surprised by the (metaphoric) moral silence shown by well meaning friends working in international law when it comes to calls for Israel's destruction. It is this silence that scares me. This is not to justify Israel's response or exonerate Hamas for its crimes. However, it seems we are in hyper partisan times especially on morally evocative issues. https://www.justsecurity.org/90358/a-plea-to-the-international-law-community-on-de-humanizing-and-the-october-7th-atrocities/