Stricken University Staff

On strike again

Next week, Melbourne Law School union branch has voted to strike for four and a half days. I will confess right now that I’m not a fan of lecturers striking for extended periods of time, because I worry about the impact on students, and upon lecturers and tutors who are in difficult financial straits. My decision to participate is reluctant.

Why am I striking, then?

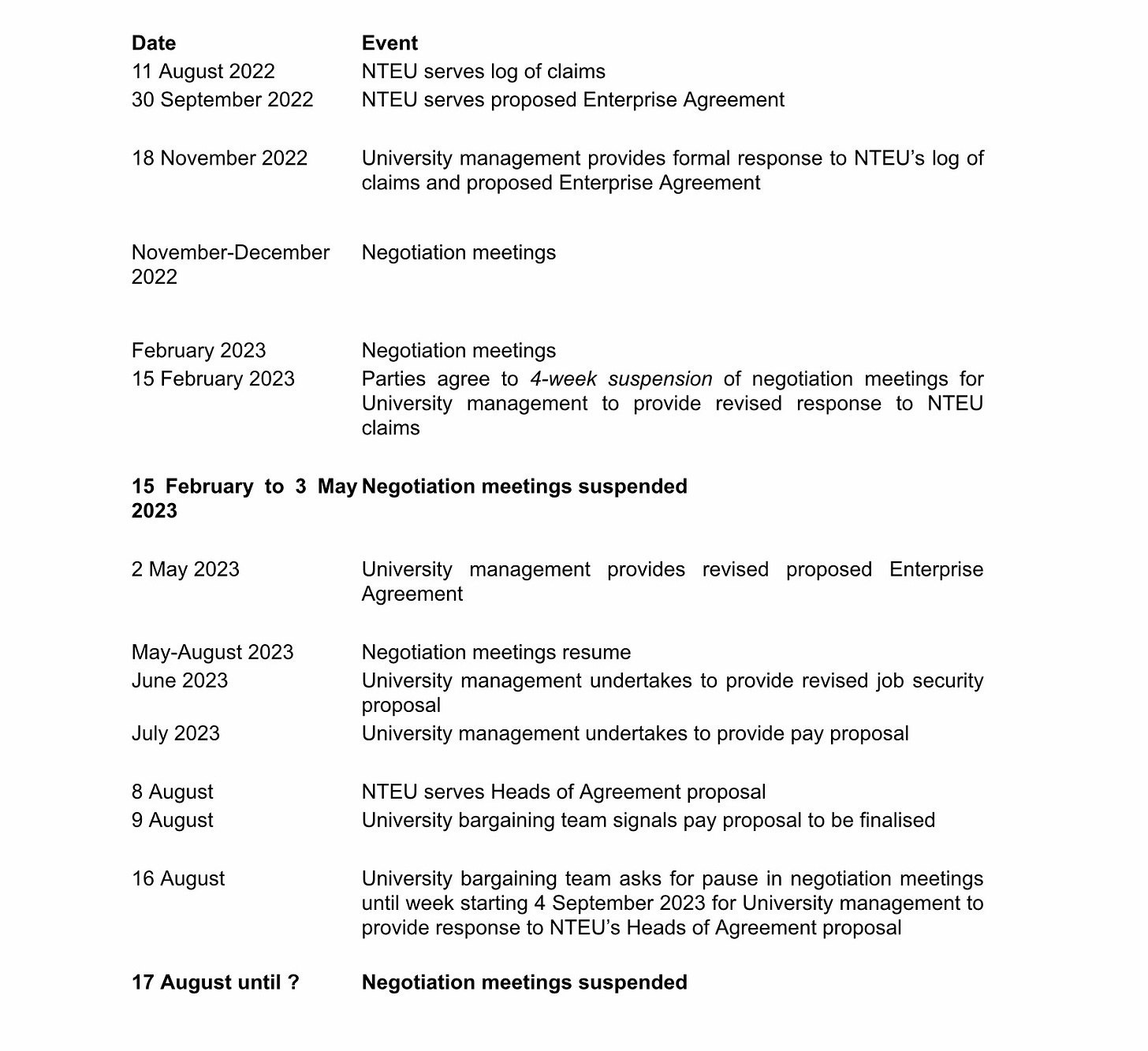

I used the word ‘stricken’ in the title to this post advisedly. That’s how staff feel: stricken. The bargaining process for our University of Melbourne Enterprise Bargaining Agreement (EBA) has been going on for over a year, and the university keeps delaying negotiations. We’re very dispirited by the delays.

I honestly don’t know what else to do, to get the message across that our system is broken. I want university management, my students, the government, and the general public to understand this.

The way in which universities are currently run, in both Australia and other countries, is intrinsically flawed. There are serious systemic issues, in part created by the perverse incentives produced by the current model of university funding by government grants. We pump out research, as evidence of our productivity; but is this really a measure of what’s important? Meanwhile, increasing numbers of students enrol in our courses, with fewer permanent staff to teach them.

I am halfway through Mary Synge’s ‘The University-Charity’ which suggests a new way of thinking about universities—one which is less managerial and which focuses on our core mission—the advancement of education for the benefit of society.1 I haven’t finished it yet, but I love what I’ve read so far. It vibes with my own view of being of service to the community, students and my colleagues. Synge focuses on English universities but says, in describing the literature about the problems of universities:

There are striking similarities in university-based literature in Australia, where casualisation of the workforce and increased class sizes are manifest, where control seem to have been placed in the hands of a ‘detached’ executive, and where universities have become ‘less sure of themselves.’ In the United States too, a similar picture of decline emerges, alongside changes in university governance which, in one writer’s words, have changed faculty-driven, autonomous institutions into organisations controlled by an administrative superstructure made up of abundantly staffed and remunerated ‘manages’, ‘deanlings’ and ‘deanlets’.2

I also just finished Christopher Beckwith’s Warriors of the Cloisters: The Central Asian Origins of Science in the Medieval World (2012, Princeton University Press). While his focus is on the origins of recursive logical argument,3 he presents an intriguing hypothesis about the origins of the modern European university. During the Crusades, Europeans were exposed to the madrasa (the Islamic colleges) and borrowed the idea for their colleges (complete with cloisters). In turn, he argues that the madrasa was based on the earlier Central Asian Buddhist college, the vihãra. There’s an ancient and rich culture of knowledge transfer and questioning across different cultures, religions and times, and we’re all part of that.

Beckwith argues that universities developed as collegial institutions, to pass knowledge on to the next generation, and to teach people how to reason, and how to question. Reflecting their origins, universities should be fundamentally collegial, with a shared responsibility for learning and advancing thought, operating for the benefit of both scholars and students.

I think we need to remind ourselves of what universities are for, and move away from the managerialism which has consumed us. It’s consumed us because of the way in which government intervention and funding of research has warped our priorities. We are a collegiate institution.

My central concern in the bargaining process is that we at least agree to reduce the level of non-permanent employment at the University of Melbourne.

All Australian universities, including my own, rely very heavily on non-permanent staff. At the University of Melbourne, a majority of staff are hired on contract. I know this well; I was on contract for four years (2006 - 2010). I was lucky to only spend four years in this position—other colleagues have been (and are still in) a much worse position. One colleague spoke of being on her thirty-seventh casual contract.

When I told my students last semester about the prevalence of casual employment at universities, they were shocked. “Surely after a period of time, if you’ve proven your work is essential, the university has to give you permanent work?” No. They don’t.

I really want this model to change, so that universities’ reliance on casual academics is the exception, rather than the rule. Academic staff shouldn’t be on casual contracts for extended periods. We need to build a path to a different employment model, one where colleagues are given more security. A lack of job security gives rise to so many problems: stress, vulnerability to sudden changes in staffing policies, lower pay and fewer entitlements, lack of staff continuity, risk of underpayment, and lack of academic freedom.

Why do universities rely on a casual employment model so heavily? I can’t speak for administrative staff, but for academic staff, I suspect there are many reasons.

Many academics shift in and out of teaching. Perhaps a lecturer goes on sabbatical, or takes long service leave, gets sick, or moves away from teaching while they are on a research grant for a few years. It’s possible to “buy out” teaching using grant money, and hire casual staff to undertake teaching roles for that time, so that an academic can concentrate on research. And frankly, given the way in which our other duties consume us when we’re teaching, I understand. Often I only get time to research in my “free time”: while the kids and my husband are watching TV, I am writing and researching.4

Sometimes, it’s related to fluctuating student numbers: if there’s a high demand for a particular subject one year, you might need more lecturers or tutors. Sometimes, a staff member might get sick: the university was forced to hire a retired staff member to teach one of my subjects last year, when I was severely ill.

In my own faculty, Law, much of the need for sessional lecturers arises from the difficulty in finding staff who want to teach compulsory black-letter law subjects, something of which I’ve written about before. It’s necessary to have a PhD to be employed as an ongoing academic these days, something that seems to have become the norm for law in the early to mid-2000s. Often, we hire PhD students, barristers or solicitors on a casual basis to teach compulsory subjects instead, but just for the time that we need them to fill the gaps.

There’s an incentive for universities to maximise the number of PhD students (again for government funding reasons). A lack of a PhD has become a barrier to ongoing employment, and the reason why some people are employed on a casual basis. This needs to be rethought. Some of the best private law academics I know don’t have PhDs. It’s more important to be a competent teacher and researcher than to have a PhD.

If someone’s main job is as an academic, lecturer or tutor, or if an employee is a PhD student or a sessional lecturer trying to obtain ongoing employment, we need to have a clear pathway towards permanency, and some certainty around that pathway. At my husband’s work, the EBA provides that his employer must offer a casual employee permanent work after a certain number of years. Why don’t we have something like that at the University of Melbourne?

It appals me that a colleague and friend in Arts has been a casual tutor for ten years or more, and is still not hired on an ongoing basis. Clearly my colleague is necessary to the ongoing success of a particular subject or subjects, or a particular research projects, but the failure to hire them in an ongoing role gives them a message that they are not valued.

Casual staff are cheaper—they don’t have the same leave entitlements and superannuation entitlements as permanent staff—and a casual staff member is easier to jettison the staff member if things change.

However, having a workforce largely made up of people in precarious employment is a recipe for resentment and unhappiness. Employees are treated as dispensable widgets or commodities, not people whose loyalty and service is valued.

My colleagues and I are also exhausted. To be honest, I think this is the case any industry which had to keep operating in COVID-19 lockdowns (at least from my conversations with my neurophysiotherapist and medical specialists about the morale in hospitals).

There are serious ramifications to this exhaustion. I had pneumonia and a serious asthma attack last year, and had to take six months off. I had a serious fall this semester, when running for a meeting. There are not enough people to teach compulsory subjects in law; the reports I’ve had from colleagues from places all over the globe is that this is a constant issue for all law schools.

As the quote from Synge above illustrates, it seems that the number of permanent people who are able to teach and undertake vital student-facing administration keeps falling, and while bureaucracy and layers of management balloon. I’m not imagining the fall in teaching resources. While the University of Melbourne placed 14th on the QS World University ranking, as this Guardian article pointed out, the rise and rise of Australian universities in the rankings comes at a cost:

Of the “big four” study destinations – Australia, the United States, Canada and the United Kingdom – which house the majority of QS top 300 universities, Australia received the highest overall score of 40.7 out of 100.

It scored top on academic reputation, citations, international faculty ratio and international research, while coming out last on its faculty student ratio which assesses teaching resources. [emphasis added]

Many processes for which one would have had help from staff members or other people in the past are now online. I cannot estimate the amount of time I waste with online “self-service”. Some platforms have driven me to tears, and I had to resign from a university role in 2021, because I simply could not work one university “self-service” online platform. It’s a false economy.

My friend and colleague Joo-Cheong Tham, one of the members of NTEU’s core bargaining team, introduced me to the concept of ‘workload creep’: that is the addition of new obligations and responsibilities without the removal of previous obligations and responsibility. It’s endemic in the academic sector. You can read the bargaining team’s excellent memo about the impact of workload increases here.

Meanwhile, as reported in the media recently, consultants are paid an exorbitant amount to make reforms. In my experience over the past ten years, as someone at the coalface, the suggested reforms have gutted the university of useful and valued employees, and left academic systems understaffed and unworkable. There’s also been a tremendous loss of institutional knowledge as many competent and experienced people leave. More consultants are hired to “fix” the problems created by the previous lot, and so on it goes.

It’s very hard for me to say this publicly, but I’ve had several moments over the past two or three months when I’ve been in utter despair, and I’ve even considered resigning. As anyone who knows me realises, this is drastic.

I have to keep reminding myself: I love teaching, I love private law,5 I love my colleagues and my students, I love my research.

I don’t think anything has been helped by the crazy state of the world at the moment. Everything is divided and fractious. Without the support of my family, friends, colleagues and students, I would have been in dire straits. I’m lucky to have you.

I’ve talked to people in management in the University. They were extremely generous with their time and listened to my concerns. I felt that they were good people, who care about the same things as I do, and who want our university to work just as much as I do.

I don’t want to have to strike to demonstrate how very upset and dispirited my colleagues and I are. It’s the last thing I want. I want us to be able to come to an agreement, and to move forward.

I plead with those who are responsible for University negotiations to resume the bargaining process—staff members are very distressed by the delays—and to please help us move forward.

We all want the same thing: a functional university, satisfied, secure staff, and students who learn and thrive. I don’t want more division and dispute. Let’s remember what unites us at university: a collegial love of knowledge, teaching and research. Let’s come together to sort this out.

I’ll review it when I finish it.

M Synge, The University-Charity: Challenging Perceptions in Higher Education (Mary Synge, 2023) 8.

I have a fascination with methods of argument in medieval times. Strangely, this has come in useful, because I had to consult St Thomas Aquinas in something I wrote this year on contract damages. SERIOUSLY.

Okay, I’m also writing fan-fiction, when I am stuck for inspiration with my academic work. It’s not all doom and gloom.

Really, I do. My students can tell you exactly how much I do.

I have been teaching at the Suburban University of South-East Queensland since 1996, and in 26 out of those 28 years have done so on sessional/casual contracts - despite having had a PhD since 2004.

Thank you, Katy, for another hard-hitting piece. Some reflection from the admin side of things: I am currently in an admin role at my university where I am one of those "self-service" support person. The job is pretty good in itself - contract based, leave entitlements, decent money, 5PM switch off (much better work conditions than casual lecturing) but these roles are generated through university projects. For some odd reason, top university management keeps taking on random projects (such as students should do exams on a laptop) then they hire admin staff to address project needs. Rinse and repeat with a new project. I realized that the people in the top love taking on new projects which keeps inflating university bureaucracy. Academics are involuntarily jettisoned into these random projects, and they grow resentful of admin staff who chase them to meet project targets. People with titles like change analysts are roped in uni staff, setting KPIs and corporatizing the long forgotten idea of university as a public good. Australian universities need a structural overhaul through improving existing processes rather than aiming to get on Top 100 uni list.