Publishing in journals

A guide for early career academics or practitioners

I’m an editor at the Australian Law Journal and the Indian Law Review. I often get requests from junior academics or practitioners to explain how the submission process works. (One day, I’ll have to explain where my fascination about Indian law came from, but that’s for another day. One of my “Indian brothers” is a subscriber; he knows the story…)

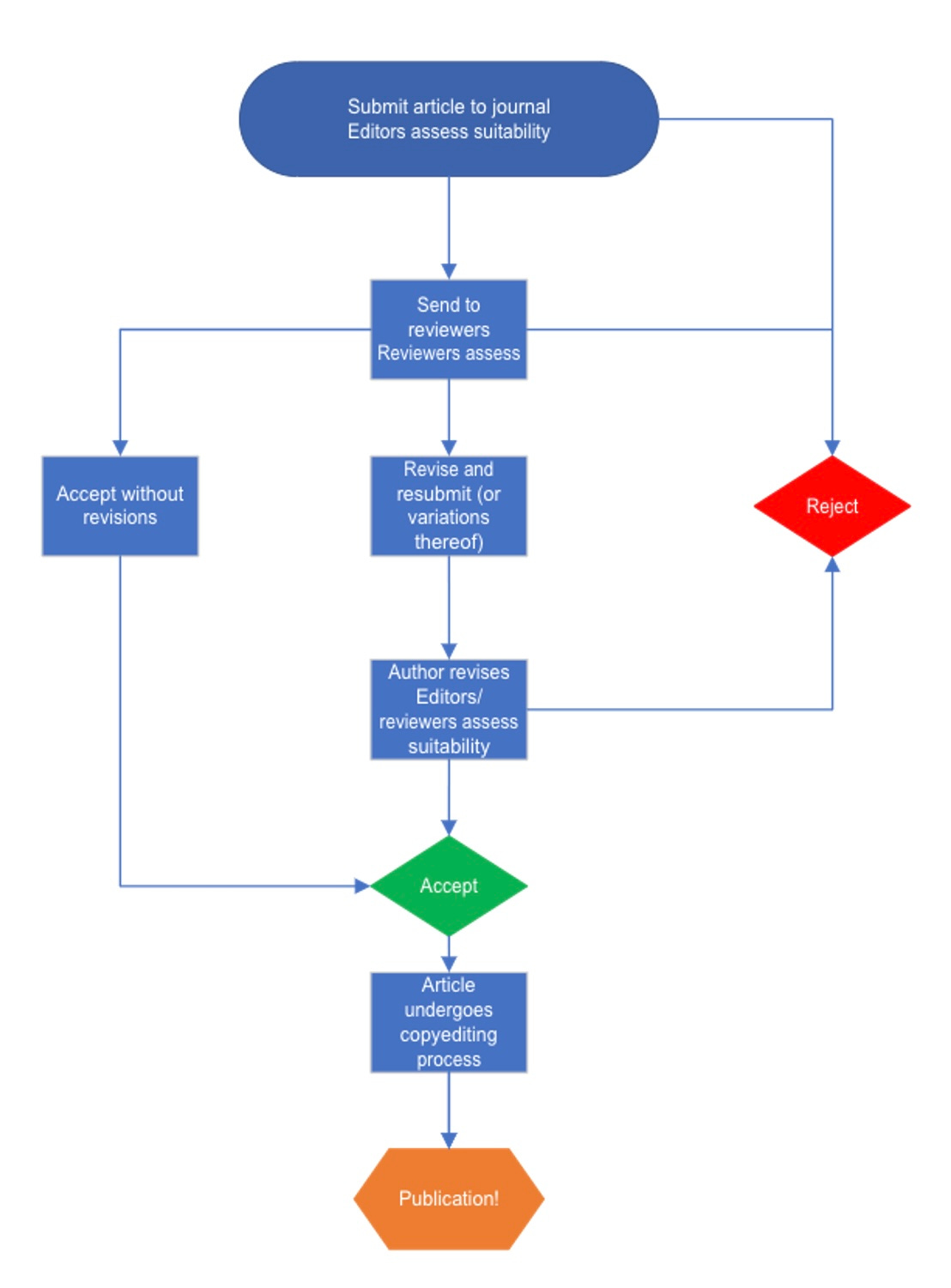

My students know well that I love a flowchart. So I created one, for the journal article submission process, for early career academics or practitioners who would like to publish:

Let’s go through each of these stages/possibilities in a little more detail:

1. Submission to the journal

Here, it’s really important that you ensure your article is the best it can be: well-referenced, comprehensive, and proof-read. (I often get other people to proof-read my work, because I’m hopeless at proof-reading my own writing).

The editors will then make a decision about whether to send your article out to reviewers. Sometimes, they will make a call and “desk reject” (immediately reject the article and not send it out to reviewers). Sometimes it’s because the article is not on the topic of the journal, or too narrow for a generalist journal. Sometimes the article is just not complete, or there is some other problem with it.

The other option is for the editors to send the article out to peer reviewers.

I note parenthetically that I have had huge trouble finding people to undertake peer review since the COVID years. I’m pretty sure, if other academics are anything like me, they were broken by that period, and are still catching up. Often I have to chase peer reviewers repeatedly for their reviews. I’m always understanding: ironically, at one point, I was both chasing someone and being chased myself. It can be particularly hard if a field is very narrow, and there aren’t many options for reviewers. I tend to ask authors or peers in those circumstances.

2. Peer review

Peer review, that fearful thing. Your article is sent out to two (sometimes three) peer reviewers, ideally other experts in your field. The peer reviewers then provide feedback on whether they think your article should be published or not.

We all love it when our article is accepted without revisions. I have 68 scholarly works, according to my University profile. I have had an article accepted without revision precisely four times in my entire academic life. Unfortunately or fortunately, this happened with my first two publications, so I had a warped view of the process at first. Usually this NEVER HAPPENS.

The more usual possibilities are that the reviewers suggest you revise your article, or they suggest it should be rejected. Reviewing is supposed to be blind. They don’t know who you are, you don’t know who they are.

Peer review is really tough. Because, as my students also know, I love Lord of the Rings even more than flowcharts, if that’s possible, I attach a LOTR meme:

If you are lucky, the reviewer will be really constructive, even if they are critical. However, I will be really frank. I have had reviewer reports which have driven me to tears before, luckily in private.1

Criticism is hard to take. I try my best to take it, and to be thankful that I’m not sending my ideas out into the world without realising someone is going to react like that to my ideas: at least I’m prepared. Often, if a reviewer is really critical, I print out the report and put it in a drawer for a week. Once it was six weeks, such was the sting.

I find that once the initial emotional assault on the brain has faded, I can usually find something useful in the feedback, even if I think some of it is unfair. The exception is that one I had to leave for six weeks. The feedback was, “I hate your article, your ideas are stupid, and by the way, I’m going to hint that I know who you are, even though this process is supposed to be anonymous.”

I’m sorry to say that most academics I know have received a review like this. I don’t know why people write reviews like this. It’s unprofessional. Yes, I have certainly rejected articles before, but I always try to be tactful and not totally destroy someone’s soul. As an editor I tend to redact anything personal.

A second annoying possibility is when the reviewer says, “The author takes x position, but really they should have taken y position, because y is better.” They want you to write the article they would have written. You can push back against these reviews, in my opinion, and say that you don’t want to take y position.

A third annoying possibility is that the reviewer totally misreads what you are doing and criticises the article they imagine you’ve written. I tend to think, when this happens, that I haven’t been clear enough about what I meant to do with the piece. It’s still useful. Again, you can push back against this, and say that you weren’t doing what they thought, but that you will be more clear about what you meant to do.

A fourth annoying possibility is that Reviewer 1 adores everything you wrote and thinks it is wonderful, Reviewer 2 hates everything you wrote and thinks it should be fired into the sun. The editors then go to Reviewer 3 for a tie-breaker. For some reason, on all three occasions this has happened to me, Reviewer 3 has been lukewarm, and the editors decide not to proceed, because those journals were so prestigious that they don’t have worry about accepting people where there’s any doubt.

Usually there is wheat among the chaff with peer review, even if there is a great deal of chaff. As I say, I have always been able to find something helpful, other than that one review.

3. Revise and resubmit

If you get a revise and resubmit, or another variation on that decision, the editors will ask you to revise your piece in light of the reviewers’ comments. With my editorial hat on, it’s really helpful if you go through your piece categorically and say where you have revised (or explained why you have not) and respond to each of the reviewer’s comments individually.

For my editorial role with the Indian Law Review, I created a table for my authors, so that they can easily show me what they have done or haven’t done.

[Please note the hopeful assumption that someone will be writing on Indian contract law. A girl can dream. And if you do want to write on subcontinental contract law, please get in touch.]

I should also say that this process can have variations and iterations. The manuscript may go back and forth, the reviewers may check whether they are happy with it, and it may have several rounds. Sometimes, at the end of all that, you might still not make the revisions to the satisfaction of the editors or the reviewers, and the piece will be rejected. (This has never happened to me, but I have heard of it happening to others.)

4. Rejection

As I said above, rejection is really tough. We’ve all had journal articles rejected, sometimes fairly, sometimes unfairly. My advice is to persist, if you can bear it, and learn what you can from each rejection. Take it as a polishing, learning exercise.

My worst experience was an article which went through five journals:

Reviewer 1 loved it, Reviewer 2 hated it, Reviewer 3 lukewarm > reject

Reviewer 1 thinks I am stupid and hates everything I do > reject

Journal said they didn’t want something on that topic and they don’t like private law any more > reject

Journal initially accepted without revision (yay!) but then reneged for reasons I’ve never understood > reject (I have to say that this one damn near broke my heart)

Journal accepted without revision.

That article has now been cited in judgments, and a judge wrote to me to say how helpful they found it, so I am really glad that I persisted. I’m glad that I didn’t listen to the person who thought I was stupid.

5. Acceptance

It isn’t all over just because your article has been accepted. It has to go through a copy editing process, and you will have to approve certain changes. The journal usually asks at this point that the changes are relatively minor.

6. Conclusion

Obviously, this is a very time-consuming process. One’s article or book chapter often comes out years after it was written and accepted, which is frustrating. Often journals have “pre-prints” to deal with this.

Sometimes it’s a little soul destroying too. Hang in there, though. Certainly, as an editor, I see my aim not to destroy people’s work or souls, but to improve people’s work, to help young scholars, and to encourage views on a diverse range of topics.

I hate crying in public; I’m an ugly crier. Not for me, the gentle, elegant tear rolling down my cheek. No, it’s the big square mouth and sobs.

Am I weird that I find it hilarious that I found an error in this as soon as I published it? OF COURSE I DID.

A fifth annoying possibility is when the reviewer thinks that they know more than you do about a point of fact that you researched exhaustively for your Doctoral thesis or other work demonstrating your expertise, requiring you to once again marshal a body of evidence to show that the reviewer is talking through their mortarboard and that your point should stand without correction.