Peer review

Reviewer 1 says peer review is “problematic and needs changing”

If you’re not an academic, you may not be familiar with the pain involved with peer review of journal articles. It goes like this. You submit your article to an academic journal. Weeks or months later, you will be given (at least) two reports by other academics, generally anonymised. The referees will advise whether your publication should be:

accepted without revision;

accepted with minor revisions;

accepted with major revisions; or

rejected.

The quality of peer review varies. In some instances, I’ve had really constructive comments, and I have genuinely valued the feedback: reviewers have pointed me to sources I missed or pointed out an error. In those circumstances, peer review is doing what it says on the box.

More often, however, the feedback you receive does not make your work better. Sometimes, it demands you totally change the focus of your work, or that you add in qualifications which distract from your main point. In the worst instances, peer review is rudely expressed, the reviewer wants you to write the paper they would have written, or the reviewer is closed-minded.

Why do journal editors ask such unhelpful reviewers to provide feedback? The truth is, it can be hard to find reviewers, particularly in highly specialised areas where most academics know one another. And if the article is outside your subject matter expertise, as a journal editor, you simply look for someone who also researches in that area and is willing to give an opinion. You don’t know whether they’re likely to be a fair reviewer.

All of this work is unpaid. One of my friends said, “How much do you get paid per journal article?” Once I’d finished choking with laughter, I managed to tell her that academics do not get paid for journal articles directly, although we will get copyright royalties. Why do we do it then? We effectively get paid for publications as part of our salary—a certain level of publication is part of our job description—and we get benefits such as career advancement and a greater chance of getting a government grant.

Peer review is also voluntary, and particularly since the COVID-19 years, people have been so busy that they found it hard to fit it in. I know that I had to turn down three or four peer review requests in the second half of 2022, when I was recovering from pneumonia. It may be that some reviewers do a cursory job, or, more often, I suspect they have very strong opinions that make it easy for them to give a swift judgement on an article. I have to think about articles for some time. I try to give constructive feedback which doesn’t impede the author’s argument too much. I hope I succeed.

As I’m a journal editor as well as an author of articles, I try to ensure that any rude comments are edited out before a review is returned to an author, and ensure that the author knows they can explain to me why certain feedback from a reviewer might be unmerited, and why they shouldn’t have to take it into account.

I can’t help worrying that peer review can produce a certain ideological conformity. Recently, I got one of those reports where the reviewer chided me for not taking the view that he or she would have liked. This is very frustrating. I don’t want to take the view this person would have liked me to take. I’m senior enough now that I can either refuse to take that view, or put in a nod to the alternative view in footnotes. For a sanity check, I showed the article and the peer review to another senior colleague and his verdict was, “This reviewer totally misunderstood the nature and the point of your article.” This was a relief, because that was my impression as well. But if I was a more junior academic, I might have felt the need to be more accommodating.

Or I might give up altogether. A friend was surprised that someone hadn’t done an economic analysis of a certain area of equity. It was then that I realised I wrote such a paper back in around 2008, but it was rejected categorically by peer reviewers on the first attempt. In the meantime, I had my second child, and I had other priorities, so I gave up on the paper altogether. An idea which might have had value was crushed, rather than nurtured. Alas, I can’t even remember now precisely what my idea was—despite my generally capacious memory for legal information—which I can only assume is related to sleep-deprivation and hormones.

Younger academics should be warned that the review process can be really tough, but it’s possible to persevere. One of my papers was rejected no fewer than four times before it got accepted. The first time, it was rejected out of hand, rudely, by a single reviewer. The second time, Reviewer 1 really loved it, Reviewer 2 hated it, and the line-ball referee they brought in was indifferent, so they decided not to publish. The third time, it got accepted for publication, and then the journal didn’t have room for it. The fourth time, again, Reviewer 1 loved it, Reviewer 2 hated it, and they didn’t bother going for a third. FIFTH TIME LUCKY! It found a home, and has now been cited in a judicial decision as “useful,” so there you go.

How did I persevere? I had a strong sense that my idea was unorthodox, but still worth mooting as a possible different way of looking at a problem, even if some people found that challenging. That being said, I had to leave the paper in a drawer for a month each time before I could bring myself to revise it and try again. Sometimes I had to leave the peer review in a drawer for a week or more, too, before I could read it again. The process I described above spanned well over two years.

As I’ve noted in a previous post, I’ve discovered that the tradition of double-blind peer review arose in the 1960s as a result of government grants, as this piece details. It was instituted as a result of the (understandable) need of governments to ensure that they were giving grant money to reputable sources trusted by other academics.

I keep wondering if there’s a better way to ensure our work is of good quality.

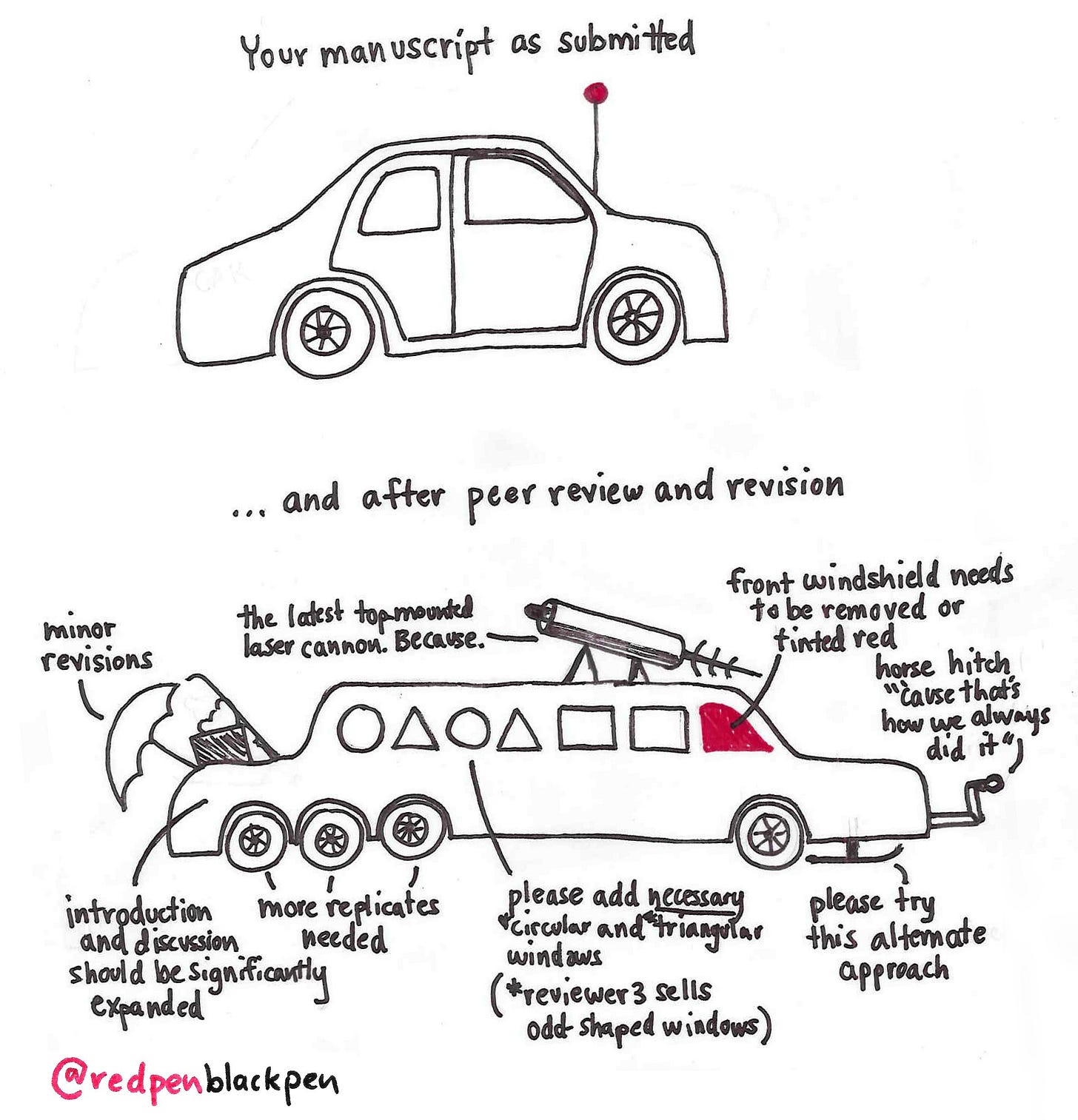

Generally, I’ve received vastly more useful feedback from colleagues and friends when I’ve shown draft pieces to them, or when I’ve presented papers at workshops. If I get negative peer review which requires me to revise my article, I try to have the strength to resist comments that will make my article look like the bottom car in the cartoon at the top of the post: random bells and whistles sticking out all over it, and irritating qualifications which don’t fit with the whole.

More broadly, I feel the academic publishing market is broken. I couldn’t afford to access my own articles or chapters, if I didn’t have institutional access. I don’t know exactly what to do about it, except to try to break the stranglehold of the ‘publish or perish’ mentality and the idea that more is necessarily better. As Stuart Ritchie has suggested in Science Fictions, when grants or promotion are given to those who publish as much research as possible, an unintended consequence is that this can incentivise fraud, negligence, bias and distortion in academic publications.1 And peer review hasn’t worked to prevent that from occurring. Nor has it worked to prevent the ‘replication crisis’ plaguing some scientific disciplines: namely that results are not reproducible when others try to undertake the experiment on subsequent occasions.

After I kvetched about my recent peer review experience, some kind person on Twitter provided me with this most excellent chart: peer reviewers according to a Dungeons and Dragons-style alignment.

Which one are you? While in everyday life, I think I’m chaotic good or chaotic neutral, and possibly even sometimes chaotic evil—note the general chaos—as a reviewer, I try to be lawful good.

While Ritchie’s book concentrates on scientific academic publications, I think many of the problems are endemic to academic publication.

Looks to be some serious "systemic" problems in virtually all of Academia.

But not sure if you're on (X)Twitter or not, but, ICYMI, here's one Twitterer who takes frequent shots at the peer-review part of that problem:

https://twitter.com/RealPeerReview/status/779780977698574336

Another fab read! As an "early career researcher" (I know people in 40s being labelled as ECRs lol- only in academia), the pressure to publish is so pervasive that you feel the need to publish whatever random brainfart comes to you on a given day and then you make it palatable to the peer reviewers as they may have a different idea of your brainfart. How they choose to convey their conception of brainfart is essentially moot. Rarely do you have the time to think critically of our own ideas and therefore sometimes peer reviews seem harsh. I feel academic world resembles corporate hierarchies where publications are your KPIs and peer reviewing is a form of power play. In a perfect world, where all academics are rational people operating under rational choice theory, they would upload papers on their own websites/substacks after they get comments from their colleagues and let people read for free and comment on it below. But nah, that won't happen would it?