What is the purpose of academia?

A genuine question

Well, that was unexpected. I was actually meaning to start this Substack to share chapters of a fantasy novel I’ve written, which I may still do if I get up enough courage. *screws up face, bites lip, trembles a little*

Instead, quite without forethought, I vented about the lack of private law academics.

It seems that I struck a chord, and that the problem of finding people to teach bread-and-butter subjects extends beyond private law to other compulsory legal subjects, and into other fields of research (commerce, dentistry, etc). From the responses I got, it also seems to be a global problem. This convinces me that I should continue to explore and discuss the general state of academia, without fear or favour. After all, I’m a Professor now, so I may as well use my position to stir the pot a little. I’ve got my spoon ready…

At the end of 2020, I wrote a piece for the Australian Law Journal, in which I said:

When I think of the impact of COVID-19 generally, I imagine a tide going out, leaving exposed on the sand all the treacherous shoals and the rubbish which we have hitherto been able to ignore because these things have covered by water. Suddenly various flaws and weak points in society are exposed, including in health, in international supply chains, and in the tertiary sector, just to name a few.

Of course I had previously been aware of issues in academia, but I had been able to float over the shoals. The COVID years meant that the various perverse incentives in operation—in academic publishing, in teaching, in grants—were suddenly laid bare to my eyes in a way which they hadn’t been before.

After my previous post about the importance of doctrinal scholarship, a friend alerted me to this piece by Geoffrey Samuel, arguing that doctrinal scholarship was not worthwhile or defensible. Once I had gotten over my immediate bristle at the fact that Samuel had likened doctrinal scholarship to astrology (one must lower those bristles, I insist, and consider it rationally) I read his piece with great interest, and found it knowledgable and revealing. In his conclusion, Samuel says:

Can, then, traditional legal scholarship be defended? The first response is to say defended from what? If nothing much is expected from academic legal scholarship in terms either of new knowledge or of epistemological insights valuable to the social sciences in general, then such scholarship can be defended. All one needs to show is that such scholarship fulfils its purpose of assisting the courts and other parts of the professional legal community. If, however, more is expected; if doctrinal legal scholarship is expected to contribute to the academy in general in respect both of new knowledge and of epistemological insights useful for those outside law, then traditional doctrinal scholarship needs defending. [emphasis mine]

It seems to me that Samuel’s piece gets to the nub of the issue. For whom do we write and research? Do legal academics write for other academics, for students, for courts and lawyers, for the general public, or for the benefit of other disciplines outside law? And what do we think our role is?

For what it is worth, I have written theoretical works primarily aimed at other academics; textbooks, chapters, articles and treatises aimed at courts, lawyers and students; non-fiction books and blog posts aimed at non-lawyers and academics in other disciplines; and (as I confessed above) fiction for the general public. Therefore my answer would be, “Personally, I write for everyone, in different ways.” But then, I must admit that maybe others do not have quite my facility to do six impossible things before breakfast, nor quite my passion for writing (of which more anon).

It struck me that Samuel assumes that the principal role of academics is to write for other academics. I note with interest that, although he mentions judges and practitioners as potential audiences for one’s writing, revealingly, he doesn’t mention students at all. I don’t blame him for that. I suspect most other academics (other than outliers like me) think that their primary role is to produce research and engage with other academics. And this is a rational belief, given the incentives in operation, unless you happen to be wandering around in an oblivious fog like me, more concerned with a recent random foray into nineteenth-century depictions of bees in law than metrics.

To be promoted in academia, it is pivotal to show that you have published in top journals, been cited by other top scholars, produced many papers and scholarly books, and gone for many grants (hopefully successfully). This is where I confess that I suspect I climbed the greasy pole despite my general obliviousness because I am a publication machine. No, I do not write to hit publication metrics, and never have done so. I write so much because I am interested in many things, and writing is how I work out what I think. Of course, then someone will come along with a comment or a counterpoint and I will have to adjust what I think, or respond to their point, and so on it goes.

I have never been successful in a government grant application. Indeed, after putting an immense amount of work into a small grant application in 2013, and failing to get it, I decided I was never applying for one again. Many universities make it compulsory for academics to apply for grants on a regular basis. I would have left academia ten years ago, had my law school forced me to do this. It is well-known that black-letter private law grant applications are mostly unsuccessful, and I decided that my time could be more profitably used in doing the two things I know I can do well: teaching and writing. I regard my solo instance of writing a grant application as a sunk cost. The fact of the matter is, as I said in my previous post, black-letter private law is not regarded as sexy, unless one can tie it to a current issue.

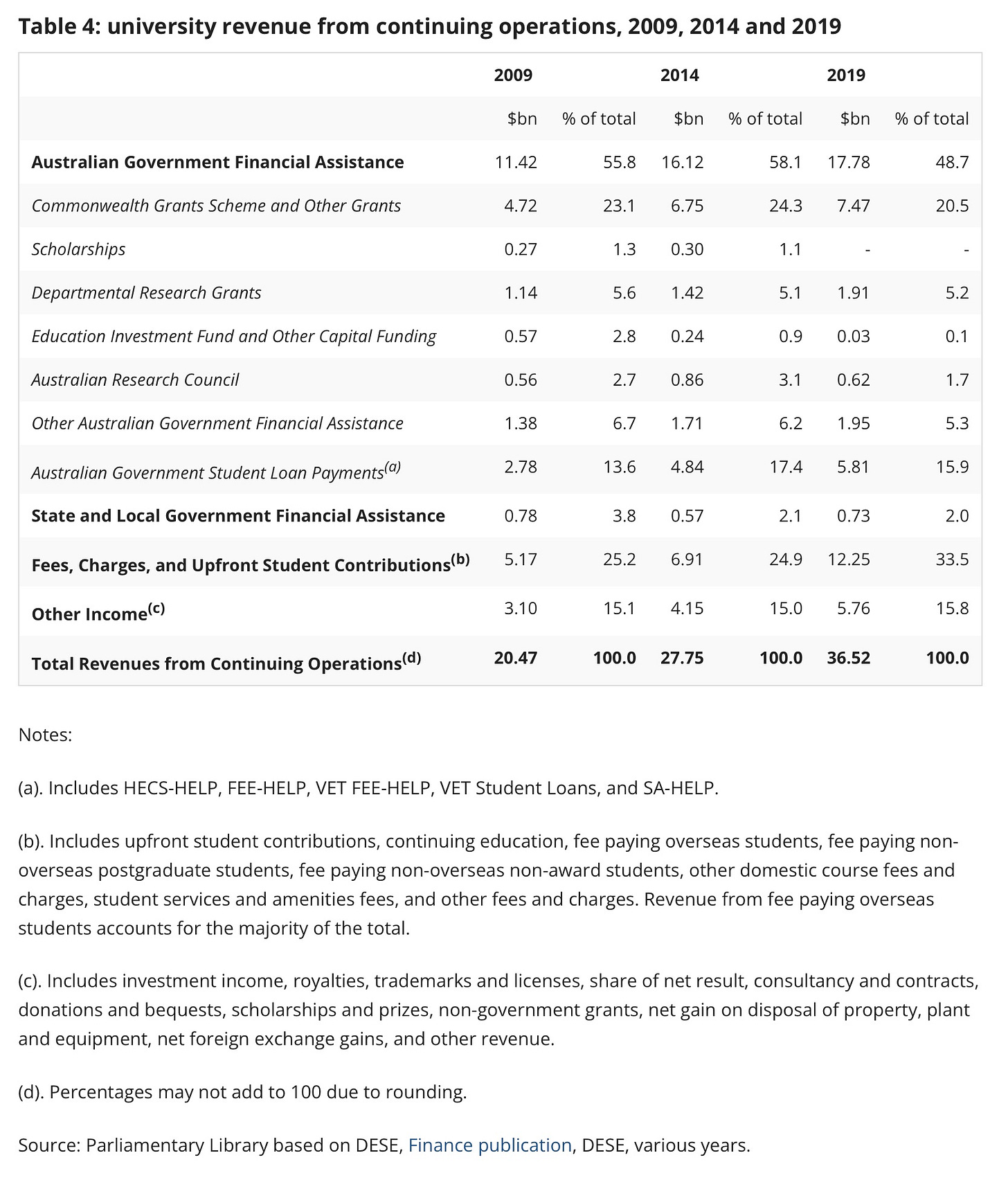

An immense amount of university time and resources go into applying for grants, and universities jealously count up who got more of the pie. According to the graph below (taken from this paper on government funding of higher education in 2021), in 2019, about 20 - 25% of university revenue came from government research grants, primarily administered through the Commonwealth Grants Scheme. A greater proportion of university revenue came from student fees (noting that the Federal government also offers financial assistance for students in paying fees).

Looking at it from the outside, I really can’t see why some projects get grants and others do not. The legal projects which get grants have all seemed worthy to me, but then so have the ones which were rejected. Sometimes I think a more fair result would be obtained by a lottery: and in fact, this is one of the solutions suggested by Stuart Ritchie in his excellent book Science Fictions, outlining the problems with fraud, negligence, bias and distortion in scientific academic publications. His book should be required reading for all academics.

Please note that, at the beginning of Samuel’s piece, and at intervals thereafter, he refers to the UK Research Excellence Framework (‘REF’). We have a similar body in Australia, the Australian Research Council (‘ARC’). These bodies assess and rank which research is worthwhile, and allocate grant funding thereby. In the ARC’s own words:

The ARC is responsible for administering the National Competitive Grants Program (NCGP), assessing the quality, engagement and impact of research, and providing advice and support on research matters.

The ARC’s purpose is to grow knowledge and innovation for the benefit of the Australian community by:

funding the highest quality research

assessing the quality, engagement, and impact of research

providing advice on research matters.

The aim of universities, concomitantly, is to rank highly in government research assessments such as those undertaken by the ARC and the REF, so that they get more grant money for research. Of course, there’s nothing an academic likes better than getting high rankings—it comes with the territory!

The government imposes these rankings because it wants to be sure (quite rightly) that it is not wasting its money, and hence it measures the quality of academic publications by using proxies such as assessments from other academics, frequency of citation by other academics, number of publications, and quality of journals. Incidentally, I recently learned that the tradition of double-blind peer review arose in the 1960s as a result of government grants - do read this excellent piece from Experimental History on the advantages and disadvantages of peer review.

Alas, I tend to think that government criteria for quality research have produced a fine instance of Goodhart’s law: “When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.” These means of measuring the quality of research produce a variety of perverse outcomes:

The ‘publish or perish’ mentality, and related problems about which I have written here, creates an environment where academics frantically publish as much as they can to meet department targets, producing so much work that, even if it is good quality, no one could possibly read (no, quantity does not necessarily mean quality).

The publish or perish mentality can also produce ‘salami slicing’: namely, cutting a piece which could be singular into several different ‘slices’ to boost your number of publications.

Citation metrics and reliance on peer review can risk the development of cliques and groupthink, rather than fresh thinking. In other words, academics within the clique cite each other to keep reinforcing the importance, impact and correctness of their views, and prevent views they regard as “wrong” from being published, even though there may be veracity to those views.

At worst, as Stuart Ritchie outlines in great detail in Science Fictions, academics are incentivised to engage in fraud and “p-hacking” to overestimate the results and impact of their research.

In Australia at least, our funding structure means lecturers must have PhDs. A lecturer can only supervise PhD students if they have a PhD, and government research funding depends in part upon how many PhD students a lecturer has, which means universities must incentivise students to do PhDs.

Academics focus on research as the main matter of importance, and teaching (despite protestations to the contrary) is not valued as highly because there are no unproblematic metrics according to which one can measure its quality. Student evaluations are notoriously unreliable. And sometimes, great researchers are not great teachers, or vice versa. (In my view, there should be a place for both pure researchers and pure teachers in tertiary education. Not everyone can do both.)

Relatedly, sometimes academics pay casual staff (sessional or adjunct lecturers or tutors) to do their teaching for them, while they complete grant research and comply with their government obligations. I was a sessional lecturer myself for four years. Casual staff have been underpaid, exploited and generally being placed in a precarious position which limits their academic freedom. Yet the grant system encourages us to perpetuate this mode of operation, because eventually the academic finishes the grant research, and there is no need for the casual staff member any more.

As academics, we have to decide what we are here for, and what our role is. Personally, I had always thought that my role was primarily to teach, and to provide a service to the public with my research (if I could afford to make all my articles open access I would, but that’s a different can of worms, don’t start me opening it … yet). In my view, universities don’t exist primarily for other academics. Universities exist for the education of students, and for the benefit of society more generally. Part of that benefit is the research we produce, which, it is hoped, is helpful for broader society, and this is why governments fund our research. But if the way in which we fund research and the emphasis on grants is distorting what we do, can we administer funding in a way which minimises perverse outcomes?

At the moment I feel a little like academics are the dog in the famous cartoon by KC Green, saying, “This is fine” while the house burns down around them.

The full version of the cartoon is here: of course it doesn’t end well for the dog.

If the incentives are perverse, how can we change them? I’ve felt strongly since 2020 that the tertiary system will founder in the shoals if we don’t change something. It’s time to think about what we can change, and what our role in society is: after all, it is society who ultimately funds us.

I hope that we can rescue some of academia. I’m aware it is at risk of being destroyed—in 2020 I was informed by people on the moderate right that they would destroy the universities in a heartbeat, other than STEM, as they think many disciplines in HASS have become utterly debased and corrupted. That’s when my bubble was popped, and I don’t think I’ve gotten over the shock yet.

I am reluctant to comment on other disciplines, it’s true, simply because the nature of academia is (unfortunately) a bubble. And until COVID hit, I lived in a very little private law bubble, where, in Australia, UK and other Commonwealth jurisdictions, at least, things mostly seem to work very much as they always have. We write treatises, we write textbooks, we don’t get grants, we teach, we engage in scholarly debate - the criticisms of friends on the right seemed overblown to me, and did not reflect my own experience of academia, where my colleagues were scholarly, rigorous and seeking truth, and (mostly) open to different views (okay, there are a few silly turf wars, but I think that comes with the territory, alas).

Moreover, I am allowed to dabble in all kinds of things, from offshore trusts in the South Pacific in one publication, to 19th century cases involving bees in another, to policy considerations for the calculation of contract damages in the next, to Indian colonial codification of law in the next. My decision not to go for grants has been a tremendous boon - it gives me more time for writing, less stress, and I don’t have to stick to one topic. I would get very bored if I had to stick to one topic for three years. There’s so much more to learn! Horses for courses, I suppose. We’re all different, and others like to mine a topic out.

I just love knowledge, and I read very widely (currently reading something on the Gunpowder Age in China, probably not relevant to my main work in contract damages, but WHO KNOWS? I read a book on the Institutional Revolution in 19th C England for fun, and discovered it was directly relevant to some of my work: watch this space, I do hope my jointly-written article on Roman and 19th C English history of currency and standardised measurement and its impact on contract law is accepted for publication (currently with referees). So I am very much into preserving knowledge for future generations, and linking things which might not have previously been linked.

But a friend in the public service (who had to deal with a bunch of academics lately) said to me glumly last year, “You know you’re a unicorn in academia? You write clearly, you have common sense, you’re practical.” I was shocked by this—the friend is generally “progressive”, and I had never expected her to be negative about academics—nor have I ever thought of myself or my colleagues as unusual. Then I began to think about her comments. I do think my field might beget clarity and common sense because it has constant “reality testing” (in the words of my friend Lorenzo). In other words, commercial law is constantly being formed and reformed on the anvil of the courts, legislature and case law, and the extent to which one can engage in fancy is therefore limited by what the courts and parliament say, and what occurs in practice in commerce. In areas which are more theoretical, where the only reality testing is by other academics, I can see how things might get out of control. I believe peer review has failed as a means of reality testing, and is mostly not useful. But THAT is a topic for another post.

Reading your first piece, it indeed occurred to me that I've seen a similar problem in my own field, and have had discussions about those issues, as well as the ones described here, with my colleagues. I noticed that they tended to think of it very narrowly through the lens of our specific field, which you initially did as well, and I think this may be related to the tendency for academia to canalize the attention of academics - most academics are very reluctant to talk about anything outside of their direct experience or area of expertise. This then has a deleterious effect on the ability of academics to take note of global problems in academia, and also I think has a negative impact on research since it incentivizes a hyper-specificity that tends to give an advantage to work of no interest beyond a very small group of scholars.

All of the problems you noted here are quite global and at the moment, rather dire. As you implicitly suggest, the way to resolve them may be found by taking a step back and asking - what are we really doing here? What's the actual point?

Because at the moment the point seems to be: climbing the greasy pole by publishing papers and winning grants.

Whereas the point should be: preserving, passing on, and extending the knowledge base of the human species. At least that's my feeling. No one ever founded a university or endowed a research chair because they thought "what the world really needs is a mountain of impenetrable garbage papers produced by hacks trying to maximize their publication metrics". Or, even worse "a jobs program for armies of useless midwit administrators", which really seems to be the main function of universities at the moment.

Sadly, after generations of the perverse incentives created by the grants system, the academy is now dominated by the sort of narrow-minded careerists whose strategies and personality profiles are optimized for winning the grants game. Genuine scholars motivated by raw curiosity and a love of knowledge are rare in the ivory tower. This is a massive obstacle for reform. It may well be that the formal academy must simply be abandoned, and reconstituted outside.