Agreeing to disagree

Learning to disagree well is an art

It’s notorious that we live in polarised times, such that civil disagreement scarcely seems possible any more. Disagreement threatens our status in a profound way. In The Status Game: On Social Position and How Use It, Will Storr explains why this might be:

Our status games are embedded into our perception. We experience reality through them. So when we encounter someone playing a rival game, it can be disturbing. If they’re living by a conflicting set of rules and symbols, they’re implying our rules and symbols - our criteria for claiming status - are invalid, and our dream of reality is false. They’re a sentient repudiation of the value we’ve spent our lives earning. They insult us simply by being who they are. It should be no surprise, then, that encountering someone with conflicting beliefs can feel like an attack: status is a resource, and they’re taking it from us. When neuroscientist Professor Sarah Gimbel presented forty people with evidence their strongly held political beliefs were wrong, the response she observed in their brains was ‘very similar to what would happen if, say, you were walking though the forest and came across a bear’.

When this happens we’re often compelled to take comfort in the presence of our like-minded kin. …

But the dream is now becoming dangerous. It takes the differences between us and our rivals and weaves over them a moral story that says they’re not simply wrong, they’re evil. …1

I thoroughly recommend Storr’s book, to help make sense of the discombobulating times in which we live.

Teaching complex and sensitive topics requires us to confront disagreement, however. Indeed, in law, disagreement is the anvil upon which the common law is hammered into shape. The common law allows a judge to dissent from the majority. In other words, where there are multiple judges, the judges can, if they want, write separate reasons as to why they decided as they did, even if their judgment does not reflect that of the majority. (This is not the case in civil law countries2). Sometimes a case has eleven different views of what the correct decision was: that of the trial judge, the separate opinions of the three appeal judges, and then the separate opinions of a full High Court of Australia bench of seven. (The majority decision in the High Court trumps the decision of the lower court, but this can lead to problems when there are an even number of High Court judges.)

The observations regarding the necessity of questioning and criticism is true not just of legal scholarship, but of scholarship more generally. In commenting on the High Court of Australia’s decision in Ridd v James Cook University,3 Josh Forrest and Adrienne Stone have argued:

academic method recognises that all research is provisional, and properly subject to testing, criticism and elaboration. Academic freedom, by facilitating these processes, is a freedom which reinforces rather than displaces academic discipline.

As lawyers and academics, we have to be able to talk about why we disagree, in a civil manner. And as educators, it’s essential that we must be able to explore disagreement. This will require courage and careful management by lecturers. Cambridge philosopher Arif Ahmed has said about free speech in the academy:

The issue is realising that your job, especially in a leadership position, can involve doing things that some people find very upsetting, and not giving in to the people who shout the loudest. Teachers need a spine as well as a brain, in universities…

Once I taught a class which featured a case of assault, Zanker v Vartzokas.4 A young woman missed her bus home and got into a car with a man who offered her a lift. Once she was in the car, the man started to proposition her and ask her to provide him with sexual favours, and then, when she declined, said he would ensure his mate would “fix her up”. She jumped out of the moving car and was injured. The man was required to compensate her for the assault and the injuries she suffered.

One of the male students put up his hand and said, “Wasn’t she unwise for getting in the car with the man? Couldn’t he say that she was negligent?”

Immediately, students began to call out, “Sexist!” “Disgusting!” and to complain about the student’s question. I asked everyone to be quiet, then I asked the student a series of questions:

Me: “What if a child had gotten into the car with the man? Would his conduct have been acceptable then?” (Student: No!)

Me: “What if a young man had gotten into the car with the man? Would his conduct have been acceptable then?” (Student: No.)

Me: “What if the driver had been female and the victim had been male? Would her conduct have been acceptable then?” (Student: No.)

I asked the student why he thought it was unacceptable for the driver to proposition a person in those other situations. He said, “Because they didn’t agree to be treated like that, just by getting into the guy’s car.”

I was able to use this as a “teachable moment”. I could explain to him that between us, we had developed a general principle that you don’t agree to be propositioned and physically threatened, just by getting into a car, and that the rule of law requires us to apply it to everyone: man to woman, woman to man, man to man, man to child. We can’t treat a woman differently, just because she’s physically weaker and more vulnerable. The driver who propositioned the passenger has committed a wrong regardless of whether the victim is male or female, child or adult.

The student said, “Oh. I understand.” I could see that he did. However, if I’d simply sat by while the class attacked him, or attacked him myself, he may not have understood in the same way. He might have changed his publicly stated view, given the outcry and outrage he provoked, but he may have retained his private view without thinking through the deeper issues.

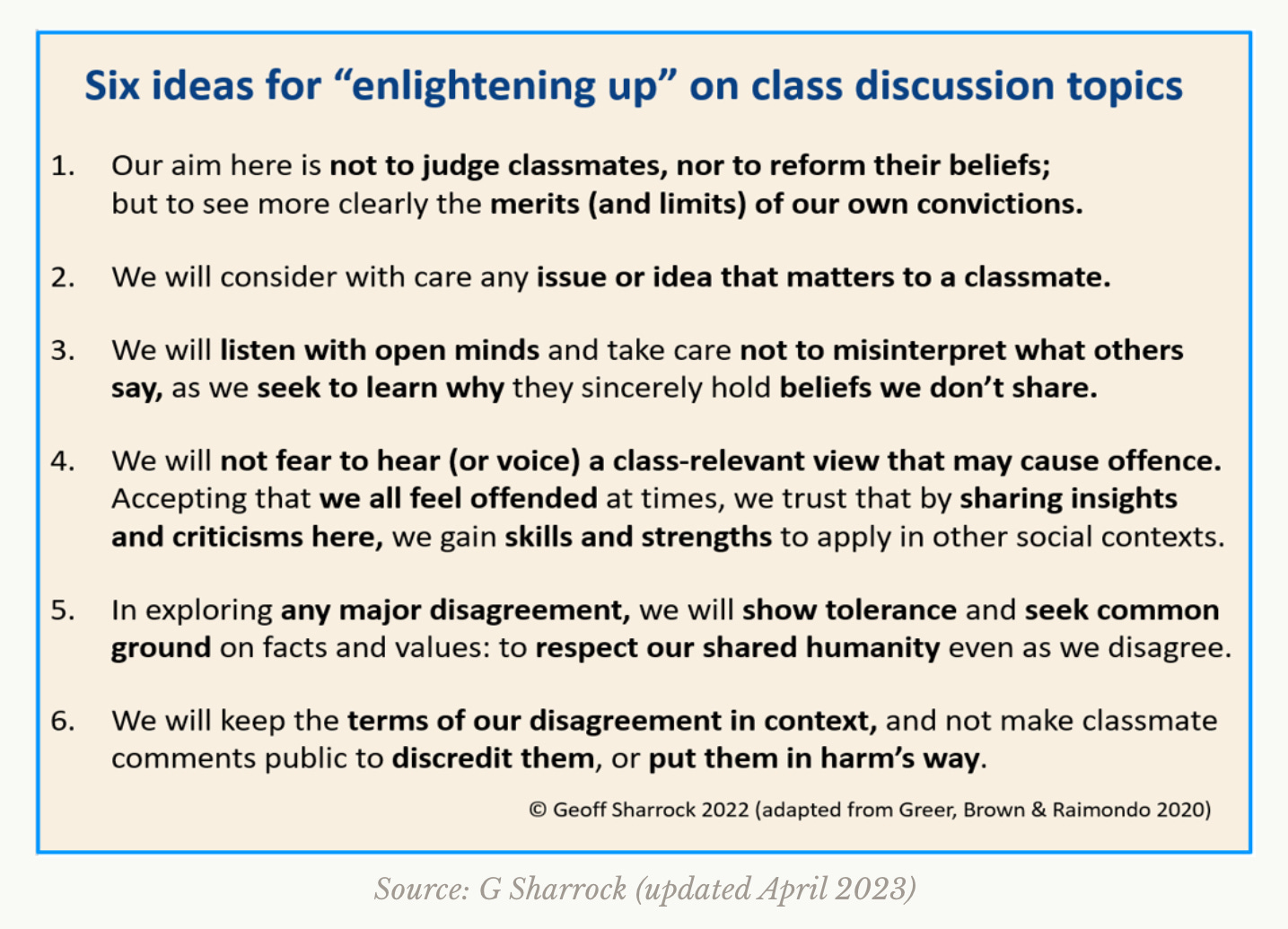

I raise this for a reason. My colleague Geoff Sharrock has been doing really useful work on how we might teach disagreement in the classroom. He suggests here that we should teach students how to disagree well.

The first step, of course, is to prepare students for the possibility that there will be disagreement. He proposes the following six ideas for students and lecturers to keep in mind when discussing contentious issues:

Sharrock also notes that there are ways to disagree well. I think this is my particular favourite of his diagrams:

All too often, the arguments we see on social media fall into categories 3 and 4. But this is not how academic argument should be conducted. This doesn’t mean that you can’t raise issues which another academic might find uncivil or challenging. Returning again to Forrest and Stone’s case note on Ridd, they say that it is encouraging that the High Court of Australia did not require respect and courtesy in disagreement, overturning the prior decision of the Full Federal Court,5 because:

…in universities such demands are inapt and dangerous, at least if applied to academic discourse. As mentioned, it is essential that researchers can freely and vigorously disagree, even in ways that would be disrespectful in other contexts. It may, for example, be necessary to point out that another academic’s research is fundamentally misconceived, sloppy, disingenuous or even fraudulent. A civility standard therefore poses a risk to the freedom necessary for academic work. As one of us has written elsewhere:

“Passionate advocacy and strong critique can all too easily be mistaken for incivility, perhaps especially when used to express ideas that are challenging and unorthodox. Evidence and reason giving are the touchstones of academic discourse not civility. “

In academia, we need to resist the temptation to call those who disagree with us ‘evil’. It is essential to use evidence and reason in criticising each other. If we say someone else is wrong, we have to explain why, using evidence and/or logical argument.

To return to the Storr quote above, it can be difficult to resist feeling like we are being attacked by a bear when we come across views very different to our own. When I get a very harsh peer review of an article I have submitted, I feel it viscerally, in my stomach, and my heart starts to pump like someone has attacked me. I tend to have to put aside the review for some time—sometimes days, sometimes weeks, and once a few months—until I can re-read it calmly, without that feeling like I’m being clawed. Often I find that there is some pertinent criticism upon a second read, although sometimes the essence of the disagreement is “this isn’t the article I would have written, and therefore it’s wrong.” That’s my least favourite kind of peer review: when the criticism isn’t even constructive.

We also need to teach students how to disagree, and to try to model effective disagreement among ourselves. It’s difficult. I haven’t always managed to disagree in a dignified way myself, although I hope that (on average) I do pretty well.

Nonetheless, in our current world, productive academic disagreement is an essential skill, and one which universities should encourage, not discourage.

[This Substack will remain free, but if you ever feel like giving a tip, here’s a link by which you can do so (but only if you want!)]

Will Storr, The Status Game: On Social Position and How We Use It (London: William Collins, 2021) 158 - 159.

i.e. countries which have a Civil Code, a trend originating in Europe, but also exported to other areas of the world such as Japan, South America etc.

[2021] HCA 32.

(1988) 34 A Crim R 11.

James Cook University v Ridd (2020) 278 FCR 566.

Good piece, and depressingly necessary.

I've saved Geoff Sharrock’s pyramid of effective disagreement and will almost certainly use it...

with a few minor tweaks (e.g. delete "campus", replace "scholarly" with "technical", add "politely" before "... explain its flaws") I will generalise it for my (engineeringy) purposes.