The scourge of spin

And how it plays into risk aversion

In 2019, I accidentally became involved in a public controversy involving my university. In typical Katy-style, I decided to post a thread of five tweets about why the former politicians and journalists attacking our university were wrong, and then I put my phone back in my bag. I had classes to teach. I didn’t give the matter much more thought, and at that point, I only had several hundred followers anyway. It turned out that no one else had dared say much publicly, and I had inadvertently put my foot in the middle of a furore. That afternoon I was contacted by the media, and in the coming days, several people had a go at me on social media, with one person implying in the press that my account was wrong.

I decided to write an explanation of why I had argued the university’s position was correct, for a national newspaper. I warned my then-Dean. She was fine with it, but said I should call central university first and warn them too. It was then that I first came across the university’s central media office. And yes, I ended up publishing a newspaper piece on academic publishing, despite the qualms of the media department.

The impression which has remained with me since that interaction, and after several others, is that marketing, PR and media-relations professionals tend to be risk-averse. This is an entirely rational approach on their part, because their role is to quell controversy, and to present a positive view of the university and its research and teaching.

In the introduction to Garrison Keillor’s radio show about the fictional town of Lake Wobegon, it is billed as the town where “all the women are strong, all the men are good-looking, and all the children are above average.” The aspiration for media-professionals is that we should be the University of Lake Wobegon. Everything must be nice: positive stories of interesting research featuring good-looking or otherwise engaging researchers; technicolor photos of diverse and smiling students holding books or looking at screens; and inspiring quotes… even if the quotes don’t make much sense.

If not done carefully, spin-doctoring, PR and marketing can involve removing honesty, nuance, and passion. Intelligent people can spot a spin-doctored media statement from miles off; those statements which sound nice, but don’t really say anything when you listen more closely. Indeed, contract lawyers have a term for exaggerated or false praise: “mere puffery.”

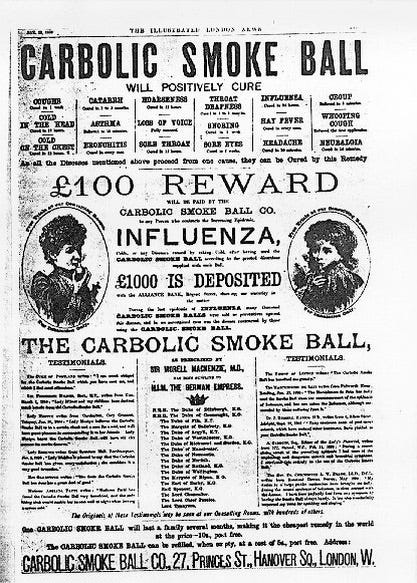

I do wonder if a long familiarity with “mere puffery” has contributed to my general cynicism about these things. Many common lawyers learn about the case of Carlill v Carbolic Smoke Ball Co1 at an early stage in their law degree.

For those not familiar with the case, Mrs Louisa Carlill purchased the Carbolic Smoke Ball after reading the advertisement above, hoping to avoid influenza during a pandemic which killed 1 million people worldwide. She contracted influenza in 1892, despite using the product as advertised. Afterwards her husband (a solicitor) wrote to the company and sought the £100 promised by the advertisement because the product had not worked. When the company did not pay, Mrs Carlill sued them. The company then attempted to argue that the advertisement was a “mere puff” (an exaggerated positive statement that anyone would know was not binding) and that the company had not intended to promise to pay. The Court of Appeal disagreed, and, among other things, said that the advertisement constituted a promise to pay if the customer used the product as directed, and that the company was bound by that promise. The mention of the deposit of £1000 at the bank was taken to show that it was not “mere puffery”.

So perhaps it is thanks to Carlill that I have a deep suspicion of overly positive statements, or perhaps (more likely) I am just a curmudgeon. However, there is a risk that emphasising a positive image could have a deleterious effect on universities in several ways, and we must be careful not to let it affect our mission.

First, research will not always garner positive results. It is imperative that we take risks in research. Sometimes you look into something, and it’s a dead end, or you don’t get the result you were expecting, or you don’t find something new, or the results are not easily summarised in a press-release. This is entirely as it should be.

There seems to be an expectation that one must be Albert Einstein, making life-changing breakthroughs. This kind of breakthrough is rare (and I note Einstein was a patent clerk when he made his first breakthrough, not an academic). We need to move away from the idea that everything (teaching, research, etc) needs to be invariably groundbreaking and innovative.

Indeed, a demand for positive publicity can conflict with the aim of scholarship itself. At its worst, as Stuart Ritchie has persuasively argued in Science Fictions, the desire to hype research by showing it is ‘impactful’ can garner fraud, negligence and “p-hacking” (torturing the data until it shows something positive).

It’s important in academia to acknowledge that research is not always successful. I am open about times when I don’t succeed for precisely this reason. Moreover, it’s important to be open about the times when one doesn’t succeed for those who follow in your footsteps.

The second risk is that if we think all the time about what our image is and whether people see us positively, it means as an institution that we become averse to risk. The only way to go through life without controversy is to never to say anything of substance. That’s just not possible if you’re a tertiary institution. There’s always going to be someone who perceives an institution in a negative light, or at least, disagrees with one of its staff members. That risk can’t be removed entirely, nor should it be.

You can’t please everyone all of the time, particularly in this age of social media. I don’t even try any more, if I ever did. I have a small but diverse group of people whose opinions I take very seriously. However, if @dongfart69 on Twitter says I’m a terrible person, or that my argument is a “bad take”, I honestly don’t care.

In a university, it is inevitable that controversies arise, and that there will sometimes be conflicts, because proper scholarship, and teaching, involves disagreement, debate, and dissent. Indeed, I believe strongly, as I have outlined in this post, that we must teach people to disagree. A university’s reputation is strengthened, not weakened, if it allows for robust and intelligent discussion, and different points of view.

I have come to the conclusion that, rather than make a life-changing breakthrough, the area in which I can make the most difference as a scholar is in teaching. If I can instil in my students a love of the law, and an understanding of its contradictions and nature, that is enough. Forget the grand goals. I can enjoy teaching my classes, inform people, be consistently curious, and go where my research takes me.

I recently hosted a visiting scholar from a prestigious overseas university. When I asked him why he had chosen me as a host, without having met me, he said, “I came here because I read a chapter in a certain academic collection by you. It was very clear. I decided that I wanted to meet the person who wrote this, and talk about my work with her.”

The best way in which we can market ourselves as tertiary institutions is not by superficial images: billboards with strange messages, or big posters of smiling students, or spin-doctored neutral statements. The best way we can advertise the quality of our institution is by investing in our teaching, and our scholarship. If our students are positive about the education they had at our institution, and if people in the scholarly community and beyond find our research useful, then that is what matters.

[1892] EWCA Civ 1, [1893] 1 QB 256 (CA).

The "@Dongfart69" cartoon absolutely rules. Chuckling away here.

And you really should read Dongfart69's book "Tantrums, Tetris And KFC: An Autobiography" it's unintentionally hilarious.