The noisy crickets

Social media, university protesters, and the amplification of shrill voices

Because half a dozen grasshoppers under a fern make the field ring with their importunate chink, whilst thousands of great cattle, reposed beneath the shadow of the British oak, chew the cud and are silent, pray do not imagine that those who make the noise are the only inhabitants of the field.

—Edmund Burke

At the moment, I feel like social media is a mistake. I have pulled back on my use of various sites, including Facebook and X-Twitter. More and more, the algorithms amplify the importunate trill of the grasshoppers, who have become so shrill as to drown out the great moderate majority, while many of us sit under the oak tree, watching, not sure how to stop society from going down increasingly polarised paths, following the noise of the most insistent. Sometimes it’s hard to hear anything else but the noise, and it feels like the world is going crazy. However, as Burke’s quote shows, maybe the world has always been like this.

I watch a lot, on social media. I don’t comment often on other people’s blog posts. If I see something I disagree with, I generally scroll on by. I didn’t used to think this way. I used to think that I could have a rational, sensible argument with people on my own blogs and my own social media profiles. Experience has taught me otherwise. There are some people you cannot have a rational, sensible argument with. Moreover, some topics are dynamite—it’s not possible to have a discussion online on these topics without it exploding into disaster—and I don’t even have the strength to go there.

There have been a couple of instances lately when I have been reminded that, although the grasshoppers on the extreme ends of opinion seem to be loudest, people are sitting and watching with horror, but unsure how to talk sensibly about an issue. A friend said to me, “Do [activists] know how they look to others?”

No, they don’t. They’re signalling to other grasshoppers, not to the cows. They want approval from their audience. Sometimes, on social media, people can even become “captured” by the thrill of having adoring fans who agree with everything they do or say, and egged into ever more extreme actions.1

The cows sit back. Maybe they don’t feel so strongly about the issue. Maybe they don’t know about a particular issue, or know anyone involved. Maybe they have other things on their minds. Maybe they are afraid of being attacked by the grasshoppers. Sometimes, however, the cows are silently judging; they don’t like the polarised, unpleasant behaviour they see, even though they don’t say anything out aloud.

Part of the problem is that the grasshoppers (whatever cause they support) tend to be obsessive and aggressive. Some years back, someone asked me, “Why aren’t you fighting back against extremists in academia?” My rather tart response was that I was too busy teaching compulsory classes, researching and writing books and articles, and actually concentrating on the core part of my job: teaching and research.

Grasshoppers devote all their energy to making noise about their chosen approach or topic. I don’t operate like that. If anything, I’m the opposite: I don’t have one topic or one view I push. I am interested in learning about a very wide range of things. I’m not generally dogmatic (although, like everyone, I have my moments). Also, I have a life: I’ve got kids, family, friends, job responsibilities, hobbies and other things to fill my time. I don’t want to spend all day telling other people how they’re wrong or evil.

As an academic, at least I have the benefit of academic freedom. At my university, the University of Melbourne, we have an Academic Freedom of Speech Policy. The principles expressed in it are creditable. Clause 4 provides:

Right to academic freedom of expression

4.1. A core value of the University of Melbourne is to preserve, defend and promote the traditional principles of academic freedom in the conduct of its affairs, so that all scholars at the University are free to engage in critical enquiry, scholarly endeavour and public discourse without fear or favour.

4.2. Accordingly, the University supports the right of all scholars at the University to search for truth, and to hold and express diverse opinions. It recognises that scholarly debate should be robust and uninhibited. It recognises also that scholars are entitled to express their ideas and opinions even when doing so may cause offence. These principles apply to all activities in which scholars express their views both inside and outside the University.

4.3. The liberty to speak freely extends to making statements on political matters, including policies affecting higher education, and to criticism of the University and its actions.2

4.4. Scholars at the University should expect to be able to exercise academic freedom of expression and not be disadvantaged or subjected to less favourable treatment by the University for doing so.

Responsibilities of scholars in exercising academic freedom of expression

4.5. Like all rights, the right to academic freedom of expression carries responsibilities. Scholars may hold their own views and speak freely on all topics, even outside their expertise, and even identifying themselves as members of the University. However, if they speak in public on topics outside their expertise, they should consider whether it is reasonable in the circumstances to link their comments to their association with the University.

4.6. Academic freedom of expression is subject to the following principles:

(a) all discourse must be undertaken reasonably and in good faith; and

(b) all discourse should accord with principles of academic and research ethics, where applicable. For example, reasons should be given for an argument so that those who wish to respond have a basis to do so and speakers may need to state affiliations (including speciality), sources, funding and potential conflicts of interest. The University recognises that these principles may vary according to the context in which the discourse occurs.

This inspired me to look into the legislative basis for our Academic Freedom of Speech Policy (as one does). Our university is legislatively required to have a policy which upholds freedom of speech and academic freedom by s 19-115 of the Higher Education Support Fund Act 2003 (Cth) (‘HESF Act’). More broadly, the fulfilment of these requirements are part of the reason for the Commonwealth funding high education institutions, and the policy forms part of the “quality and accountability requirements” outlined in s 19-1 of the HESF Act. Pursuant to s 19-75, a university is required to inform the relevant Minister of any events “that may significantly affect the provider’s capacity to meet … the quality and accountability requirements.” A failure to comply will lead to a fine of 60 penalty units.3

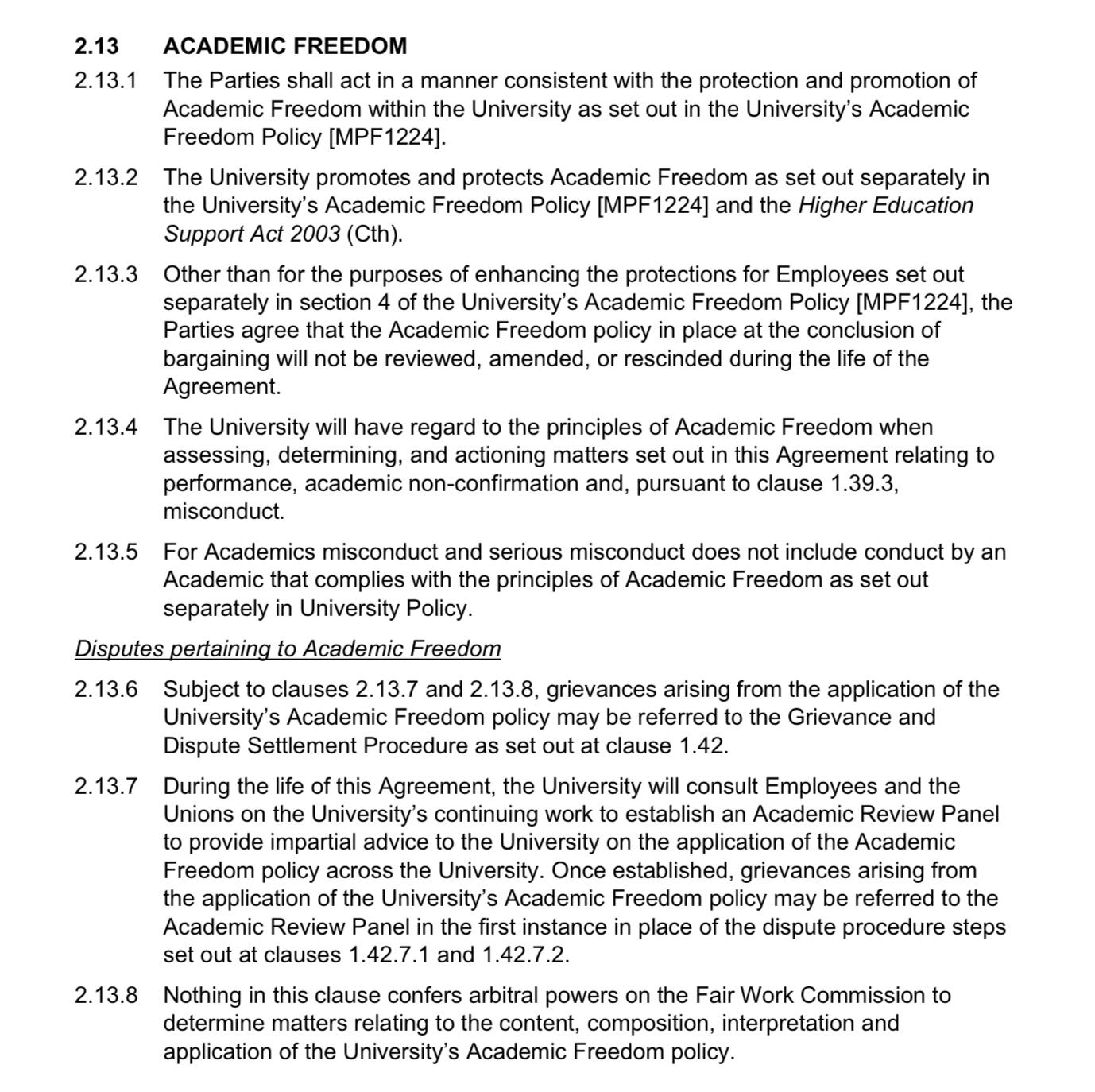

My university is also bound by our new Enterprise Bargain Agreement, which just came into force on 10 April 2024. Relevantly, clause 2.13 provides for a process to resolve disputes raising issues of academic freedom. As cl 2.13.7 notes, the university is to establish an Academic Review Panel, to assess grievances relating to the application of the Academic Freedom Policy.

I am glad this clause was included. It’s of absolutely no use to have a policy supporting academic freedom if, in practice, violent or aggressive protestors can stop academic discussion, because the individuals involved are too scared to speak, or too scared to host a particular speaker. We must have clear ways of dealing with this situation, and not just be reactive to particular incidents involving particular conflicts.

As I explain to my students when teaching Remedies law, to have teeth, laws must be backed up by consequences if they are not complied with. Grand statements are not always enough. Ibi jus, ubi remedium (“where there’s a right, there’s a remedy”). If there’s no consequence or remedy for contravention of a policy, and no way of ensuring people can safely exercise their right, then the “right” starts to look rather weak.

While I was involved in protests as a student, it was always in furtherance of some goal (a more nuanced understanding of native title law) or in protest against some policy measure I thought was bad (increased student debt). I do not recall ever protesting against an individual speaking, or trying to prevent anyone from speaking. On the contrary, I’m always curious about the arguments someone might make. I want to question them on why they believe that, and what basis they have for it, to understand what makes them tick.

If academics and students cannot speak because we are worried about uncivil protestors, it creates a very dangerous precedent. And I don’t care whether I agree with those who speak or not. A rule supporting academic freedom has to be evenly applied, regardless of individual prejudices.

Think of a topic that you’re very passionate about. Imagine that your favourite speaker on the topic comes to speak at your university. Imagine, however, that there are others who disagree with this speaker, and they prevent the person from speaking.

It’s really important not to think about this in terms of “I don’t like X—it’s dangerous and evil—therefore it’s right to ban discussion of X and chase anyone who talks about X away.” This seems to be the default for many people, particularly on social media. Instead, it’s really important to flip the situation around and think about this situation in terms of, “I am really passionate about Y. Some other people are not, and think Y is evil. Would I really want people to be banned from talking about Y?”

The probability is that you would not want people to be banned from talking about Y. You may say to me, “Oh, but I believe Y is not evil, whereas X is totally evil. I know it’s evil!” However, those who oppose Y also genuinely believe it is totally evil and harmful to certain people or to society. Should they be able to silence speakers on Y?

In part, my point is a pragmatic one: if you use a certain weapon on a group you dislike, the group will retaliate by using the weapon on you. Is this really the kind of tit-for-tat behaviour we want to encourage: a constant vendetta of cancellation and protest? It’s certainly not what I want to encourage. To allow the most violent and noisy to triumph undermines civil society.

Please note, I am using the lacklustre terms X and Y because to use any real world examples—even, I suspect, Australian Rules Football clubs (something I tried in an earlier draft of this post)—will push people’s buttons.

When faced with a “hot-button” topic, many people suffer an amygdala hijack: a strong and overwhelming emotional response to a particular topic or idea which may be disproportionate to the threat. Their bodies are flooded with adrenaline and cortisol, and the frontal lobes of the brain (the parts which control our rational thoughts and calm us down) are overridden.

I am as susceptible to this as anyone. Knowing this, I try to guard against it, and wait until I have calmed down, before I respond to things (always leave emails written in this state in the draft folder). I also try to avoid media which attempts to push my emotional buttons. I want to respond to something calmly. As I have noted in an earlier post, I do have a bad temper, and I have to keep a check on it.

We do not want protestors to dictate what we can and can’t say, and what we can and can’t listen to. In that way, we allow an amygdala hijack of civil society. As I said last year, on this same topic of violent protest:

Many of us, I think, hope that if we feed the beast of political extremism, and placate it and do what it says, maybe it will settle down and stop biting us. In fact, the opposite is true: the beast learns that its tactics are successful, and keeps demanding more. The extremist beast does eventually go away. This is in part because it eats itself, and in part because no society can sustain reigns of terror indefinitely. But the scars inflicted by the beast last.

I do not want us to go down a path where the shrill crickets destroy the academy and our ability to have a sensible discussion. At its extremes, this leads to very bad places indeed. An important function of the academy is to allow people to raise views we may find offensive, and to allow people with diverse points of view or backgrounds to speak, as the University of Melbourne’s policy recognises in a very clear manner.

I don’t know what I am precisely—neither cricket nor cow, perhaps a random stubborn goat who has wondered into the field? or given the name of this blog, maybe I’m a katydid?—but I do know that I want calm discussions of issue, and I want a clear process for dealing with any aggressive threats against academics who teach classes, give talks, or host speakers which draw the ire of protestors.

There is always the risk, too, of audience capture. Gurwinder has written of the most startling incident of audience capture I’ve ever heard of: vegan guy turns into extreme eating YouTuber and becomes morbidly obese.

Well, thank goodness for that, says this little black duck. 😁

Currently the penalty unit is indexed at $192.31 (1 July 2023 - 30 June 2024). 60 penalty units therefore means a fine of $11,538.60.

I think there's one other tactic the grasshoppers use against the cows - namely they wrap their side/issue in nice and try to make it so that the cows will feel that opposing this particular grasshopper means they are nasty people.

I think this is a tactic that is beginning to be seen through - at least in certain areas/issues

Very well put. Also, I think this is the only time I'd be happy to be called a cow.