The history of engagement rings

Restitution, breach of promise and marriage law

Why do we have engagement rings in Western societies? And who owns the engagement ring, if a couple split up after engagement, but before the wedding takes place? The latter question was explored recently by the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts in Johnson v Settino, but before turning to that case, it’s necessary to look at the strange history behind engagement rings.

The ring as a symbol of a pledge to marry has a long history, dating back at least to Roman times. At different times, the popularity of such rings has waxed and waned, but rings have always had a special place as a gift indicating an intention to marry. The modern diamond engagement ring is inextricably linked to the rise and fall of the action for breach of promise to marry.

If a man breached a promise to marry, the woman could sue for damages (these awards were sometimes poetically called “heart’s balm”). The cases tended to operate only in one direction, because of the sexual double standard.

The action of breach of promise to marry became important from the eighteenth to the early twentieth century, as a result of a peculiar set of legal circumstances.1 Until the seventeenth century—notwithstanding the Reformation—English marriage was governed by canon law and the ecclesiastical courts, which recognised marriages contracted by consent, without any particular form or ceremony. Clandestine marriages were common and corrupt practices grew up among clergy to let these marriages pass. However, common law courts did not recognise these marriages as legal for the purposes of legitimacy, property transfer, and entitlement to a husband’s estate, without a subsequent church ceremony. Sometimes parties to a marriage were left in an invidious position, or, in the case of women, left holding the baby.

In response to these problems, the Clandestine Marriages Act 1753 (26 Geo. 2. c. 33) (also known as Lord Hardwicke’s Marriage Act) was enacted. It required a particular form of marriage ceremony conducted by an Anglican minister (with Jews and Quakers being exempted) and the consent of parents for parties under twenty one years of age. This created difficulties of its own (particularly for Catholic and non-conformist Christians and non-Christians) and later the Marriage Act 1836 (6 & 7 Will. 4. c. 85) allowed for any places of worship to be registered for entitlement to solemnise marriages.

At the time when the Clandestine Marriages Act was passed, both ecclesiastical courts and common law courts began to refuse to recognise contract marriage as valid. However, to get around circumstances where the parties had behaved as if it was valid, the courts allowed women to sue for breach of promise to marry. Lawrence Stone has observed:

By the mid-eighteenth century, therefore, the breach of promise action was firmly established in common law and was filling an urgent need. It also fitted the mood of the times. It was no accident that the growth of the action coincided not only with the abolition of contract marriage by the Marriage Act of 1753, but also with the extraordinary emphasis in novels and public discussion upon the plight of respectable virgins seduced under false pretences and left pregnant and unmarried.2

He identifies three broad classes of case where women tended to pursue actions for breach of promise:

Women who had fallen pregnant after exchanging promises of marriage which were repudiated.

Women who had agreed to a future marriage with man struggling to make his way in the world, and who remained faithful for years, and then learned that the man had married someone else. These woman had rejected other suitors and sought compensation for their entry onto the marriage market at a late age.

Women (often mature widows) who had agreed to marry after careful negotiations, set a day, bought clothing and wound up their business affairs, when the man called off the wedding. These women sued for compensation for hurt feelings and blighted hopes of a husband.3

From the mid-nineteenth century onwards, the action for breach of promise to marry came to be criticised, on the basis that it favoured gold-diggers and those with a mercenary concept of marriage, forced couples into loveless marriages, and was unduly biased in favour of women.4

In the wake of this criticism, many common law jurisdictions began to abolish the action.5 How, then, could a woman be assured that if a man promised to marry her, the promise to marry would be fulfilled? This was particularly an issue where the woman had slept with the man, in reliance on the promise to marry being fulfilled.

This is how diamond engagement rings became so popular. De Beers, the famous diamond retailer, suffered during the Great Depression and had to close down its diamond mines, but in 1939, a De Beers representative travelled to the United States to spruik the advantages of diamonds.

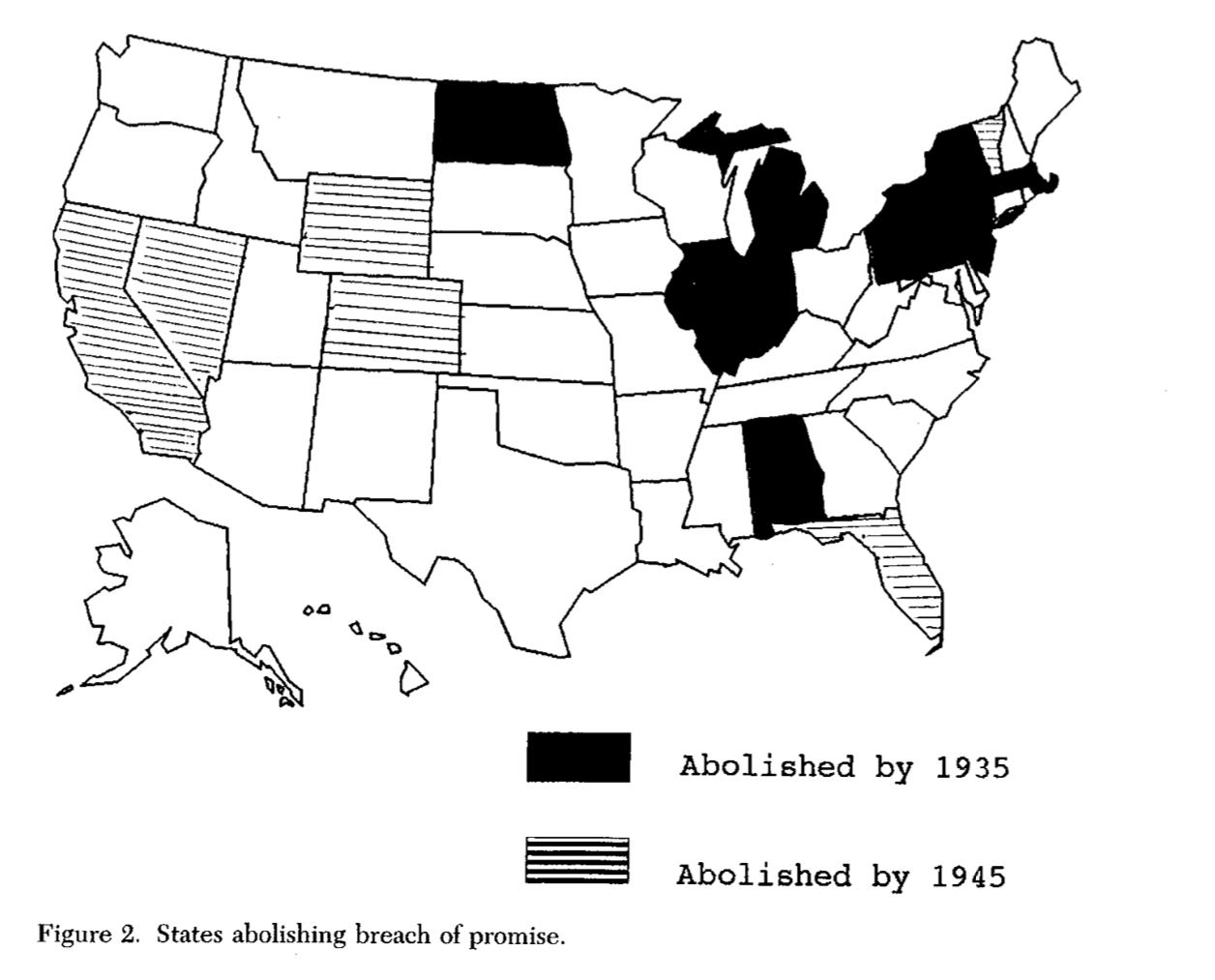

Margaret F. Brinig argues that this campaign was so successful because breach of promise was abolished in many States: a diamond engagement ring came to symbolise a form of security for the woman.6 In other words, if the man failed to go through with the marriage, the woman could keep the very valuable ring, now that damages for breach of promise to marry were no longer available.

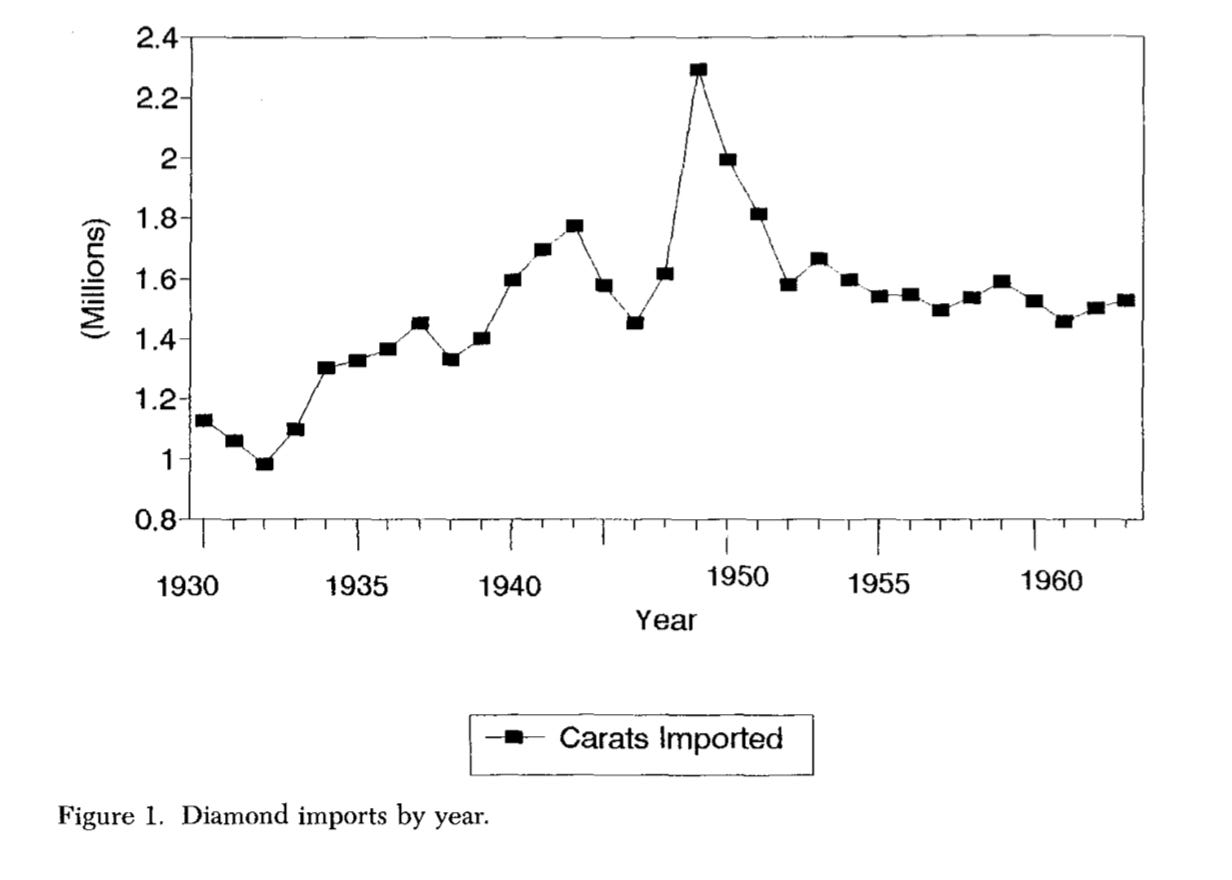

Please note the particular spike in 1949, shortly after the slogan “A Diamond is Forever” became part of De Beers’ marketing campaign. Brinig identified a correlation between popularity of diamond engagement rings and abolition of an action in breach of promise in particular US States.

Obviously the role of engagement rings has changed entirely since then, as the role of marriage in society and expectations about pre-marital behaviour have shifted vastly. Therefore, in the current day, a ring is seen not so much as security, but as a conditional gift.

A recent Massachusetts case, decided in 2024, reflects this shift in role beautifully. Massachusetts passed the “heart balm act” in 1938, which provided in § 47A:

Breach of contract to marry shall not constitute an injury or wrong recognized by law, and no action, suit or proceeding shall be maintained therefor.

There was a question, therefore, whether this provision precluded the donor of an engagement ring from suing for its return. In the 1959 case, De Cicco v. Barker,7 the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts decided that this provision did not preclude recovery of the ring, on the basis that it was a conditional gift, given on the basis that a certain event would take place (marriage) and equitable restitution was allowed. In Anglo-Australian parlance, we might look at this an instance of “failure of consideration”:8 a removal of the reason for the transaction giving rise to a right to rescind the gift or a restitutionary remedy. However, the court in De Cicco v. Barker held that the donor was only entitled to recovery of the ring if he or she was “without fault”.9

In the 2024 case, Johnson v Settino,10 the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts decided that Ms Settino had to return the $70,000 diamond engagement ring given to her by Mr Johnson, and the two wedding bands, after the marriage was called off. Ms Settino unsuccessfully argued that this should be treated as an unconditional gift. The court treated it as a conditional gift, predicated upon the occurrence of marriage, but set aside the “fault” requirement, identifying several reasons why it was inappropriate. First, it is inherently difficult to establish who was at “fault” for the breakup of an amorous relationship. Secondly, to ascribe “fault” in relation to the breakdown of an engagement is at odds with the purpose of an engagement (to allow a couple time to test whether they really do want to marry or not). Thirdly, the “heart balm act” removing the right to sue for breach of promise to marry was intended to prevent messy and acrimonious disputes about who was at fault. Fourthly, fault is largely irrelevant to modern divorce proceedings, and it follows that it should be irrelevant for such proceedings as these, too. Consequently, there was no need to look at whether Mr Johnson was at “fault” for the breakdown of the engagement.

Cases involving the ownership of engagement rings reflect deeper shifts in the legal, economic and social attitudes to marriage and pre-marital intimacy, in a fascinating way. They illustrate how societal mores governing marriage have changed hugely in Western societies, in a relatively short time.

See generally, for a history, Lawrence Stone, Road to Divorce England 1530 - 1987 (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1990).

Ibid, pgs 87 - 88.

Ibid, pg 88.

Ibid, pg 92; Rosemary J Coombe, ‘‘The Most Disgusting, Disgraceful and Inequitous Proceeding in Our Law’: The Action for Breach of Promise of Marriage in Nineteenth-Century Ontario’ (1988) 38(1) University of Toronto Law Journal 64.

It was also abolished in Australia (Marriage Act 1961 (Cth), s 111A) and England and Wales (Law Reform (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act, s 1).

Margaret F Brinig, ‘Rings and Promises’ (1990) 6 Journal of Law, Economics and Organization 203.

De Cicco v. Barker, 339 Mass. 457, 459 (1959).

Fibrosa Spolka Akcyjna v Fairbairn Lawson Combe Barbour Ltd [1943] AC 32.

De Cicco v. Barker, 339 Mass. 457, 458.

SJC-13555.

The sexual double standard: also known as attempting to deal with asymmetric risks. Those risks have, of course, also been changing rather quickly.

Beach of promise of marriage is the only tort to inspire a 19th century comic operetta: Gilbert and Sullivan’s Trial By Jury.