Suing inanimate objects

The ancient law of deodands

There was a time, in both English and Australian common law, when people injured by a thing could sue the thing itself for any injury the thing caused to them. This law was called the law of deodand (from the Latin deo dandum meaning “given to God”). This may seem ridiculous. How can things be sued? How can you blame a thing for injury? Well… think of the last time your printer malfunctioned and you swore at it, and maybe even gave it a smack. Humans have a psychological tendency to anthropomorphise things which either harm us or help us.

In most ancient European societies (Greek, Roman, Teutonic, Celtic and Scandinavian cultures, among others) a domestic animal or thing which caused someone’s death or injury had to be given to the victim or the victim’s family, to allow retribution to be exacted on the animal or thing, or to accord some kind of reparation. An item which caused someone’s death became tainted and became known as a ‘bane’.1 The giving up of a harmful item or animal was known as ‘noxal surrender’, from the Latin noxa, meaning ‘guilty body’. Please note the elision of animals and things in this rule. In Roman law, people, things and animals could all be categorised as ‘things’ for which another could be held responsible.

We have records of the Ancient Greeks punishing both animals and inanimate objects which caused injury or death (including spears and statues). Pausanias describes a case where a statue of a famous Olympian athlete, Theagenes of Thasos, killed a man.2 Theagenes’ rival had been in the habit of visiting the statue at night, and whipping it, but one night, the statue fell on the man and crushed him. The man’s sons then sued the statue, which was exiled by being tossed into the sea. However, the land then became barren, and the Oracle of Delphi advised that it had to be restored. Luckily some fishermen were able to recover the statue in their nets, and restore it.

Roman law made owners liable for the harm caused by animals and slaves, and even sometimes, the parents of children. In relation to slaves or sons-in-power, the owner or paterfamilias respectively had to pay compensation or surrender the wrongdoer into debt bondage.3 Debt bondage was abolished in the later Roman Republic.4 In relation to animals, the owner of a domestic animal who had injured a person was obliged to either surrender the animal (noxae dedere), or to pay compensation for the damage (pauperies). Initially, surrender of the animal was the usual remedy, but later, damages were regarded as a preferable remedy. When an animal caused harm, for the owner to be liable, the action of the animal must have been out of character, and not because it was in pain.5

The origin of the English law of deodand likely go back to Anglo Saxon times, perhaps with some Biblical influence as a result of the provisions in the Book of Exodus about ‘goring oxen’.6 In the Book of Alfred, there were provisions for the noxal surrender of trees: if a tree fell on a man and killed him while it was being felled, the wood was to be given to a victim’s family.7

Sutton argues, however, that there is little evidence of the uses to which the deodand was put before 1194.8 In any case, the law of deodand was taken up by the Norman conquerers of Britain and the monarchs thereafter. Typically, if a person died, the coroner would determine what thing or animal caused the death, and demand that it be forfeited, and also cause the owner to pay the value to the state, where it was to be applied for general charitable purposes,9 or sometimes for the benefit of relatives of the person killed or other poor people.10 A jury of twelve locals assessed the value of the thing which had caused the death. Of course, there was always an issue as to what precisely caused the death, and there was a suggestion in some commentaries that the cause must have been in motion in some way, which allowed juries some leeway in determining the cause.11

Things which were subject to deodand included not only animals, particularly horses and pigs, but also cauldrons, boats, ladders, bowls, carts, wheels and rope.12 I highly recommend this post on the medieval deodand on the Legal History Miscellany blog by Professor Sara M. Butler (whose work I have consulted on other matters of legal history):

Part of the problem, of course, is that there was no law of deodand clearly spelled out for medieval coroners and their juries to implement. The one stipulation that appears in both the legal treatises and the legal record is that movement matters: omnia quae movent ad mortem sunt Deo dandum (“all things, which while in motion cause death, are to be given to God”). While this may seem a minor stipulation, it made an enormous difference in terms of exactly what was eligible for forfeiture. To offer an example: an inquest, dated 3 Sept. 1377, into the death of William Wanter of Stoke Goldington (Bucks.), recounts how the deceased went to the fulling mill at Stoke Goldington on the River Ouse and was killed there by the mill, his body later found lying in the water by his wife. Rather than pronounce the entire mill deodand, the inquest jury instead narrowed their sights on the (unspecified) moving part, which they appraised at 3s. For the miller, this declaration meant the difference between an oppressive fine for unsafe conditions at his mill versus the loss of his livelihood altogether.

Compassion is apparent also in the jury’s verdict in an inquest dated to 28 Aug. 1386 over the body of Maynard Fanyeheline, a ten-year old German boy living in Boston. The boy was epileptic. While standing onboard a ship called the Mary Stantem at the port in Boston, he suffered a seizure, causing him to fall from the ship. The ship was lying between some rocks, such that when he fell, he hit the rocks and smashed his head. He did not die immediately – rather, he languished for two days before the injury finally took its toll. In this instance, the jurors could very well have declared the ship deodand and had it confiscated; instead, they placed the blame for Maynard’s death on the rocks, assessed at 4d.

The jurors’ determination in the death of Maynard Fanyeheline hints at their admirable creativity in implementing the law to prevent the deodand from impoverishing fellow Englishmen and women. Something similar is evident in the 1378 inquest into the death of Thomas Ballard of the parish of Clyve (Kent). The shipman was “carelessly standing upon a manure heap” on Billingsgate wharf, trying to unfasten an empty boat called “cokbot” moored there, when the heap collapsed inward. Thomas was thrown into the Thames and drowned. The jury declared that the boat did not move throughout the process; thus, it was the bottom of the manure pile that was really to blame, and it had no value worth confiscating.

Of course, people called for the deodand to be abolished—it was particularly deleterious to carriers, such as carters and ship owners, and incentivised people whose items had caused the harm to flee or try to hide the damage—but as Butler goes on to explain, it advantaged the monarch to keep the deodand:

Petitions presented in the House of Commons demonstrate that the seizure of goods as deodand was disastrous for trade relations. In November of 1381, a petition showcased concerns about foreign merchants and their willingness to come to England to trade. For them, the deodand was a bizarre custom – nothing like it existed anywhere else in Europe – and they were sometimes reluctant to take on the added risk that trade in England involved. As the petition explains, foreign merchants needed to be treated amicably – and the forfeiture of their ships through the deodand did not fall into that category. The plight of the Fredeland, a Hanseatic ship from Eastland, demonstrates just how risky trade in England might be. The Fredeland was anchored at the port of Great Yarmouth (Norfolk), when “certain men floating carelessly by night in a boat ran upon the cable thereof and were drowned.” As the complaint heard in Parliament recounts, the merchants aboard the ship knew nothing about what had happened. Nor was their behavior at all reckless or irresponsible: it was merely an accident. And yet, the ship and all its contents were seized as deodand. The appeal before Parliament held in favor of the Fredeland: they declared that the ship should not be held for deodand.

Parliament also expressed numerous concerns about the deodand and its impact on domestic shipping. In 1377, they reported that many English subjects have been “greatly injured, and many of them ruined, because their ships and boats have many times in the past been forfeited to the king and to other lords of franchises” through deaths by misadventure. And because of the forfeitures,

said lieges have no means to keep ships, or invest their money in the making or repair of the same, as they did in the past, to the great reduction of their fleet and harm to the land.

Thus, the House petitioned the king to abolish the custom, at least as it applies to ships. His answer: “The king will readily do that for all who wish to plead theron in particular, saving always his regality.” That is, he would not eliminate the custom, but he might consider waiving it, if a ship’s owner complains sufficiently.

In 1381, Commons again complained that if the king did not modify the forfeiture of ships and vessels on the sea and in fresh water by way of deodand, he will see the consequences of his actions. Deodand “contributes greatly to the reluctance of men to build new vessels, and if it endure it will destroy the fleet forever.”

Finally, in 1399, Commons adopted a new tack. Their complaint focused on flat-bottomed boats, used to ship wares up and down the river Thames. Noting the vast range of accidents involving these boats, “through the breaking of the cable, rope, sprit, or mast of a flat-bottomed boat,” resulting in forfeiture as deodand, the complaint explains that no one dares make flat-bottomed boats anymore,

to the great detriment of the lords and commons of the aforesaid realm, and this is a major reason why victuals and various other commodities are dearer, both in London and elsewhere in the country, because of the lack of flat-bottomed boats to transport them.

They respectfully requested that in the future, such ships not be subject to forfeiture.

The crown’s response was as one might suspect: silence. Why give up such a lucrative privilege? It made more sense to keep the privilege in place and simply waive it when seizure of a ship as deodand might damage international trading relations or enrage a loyal servant. Moreover, doing so only emphasized the king’s reputation for mercy, painting him the magnanimous lord who puts his subjects’ needs before his own.

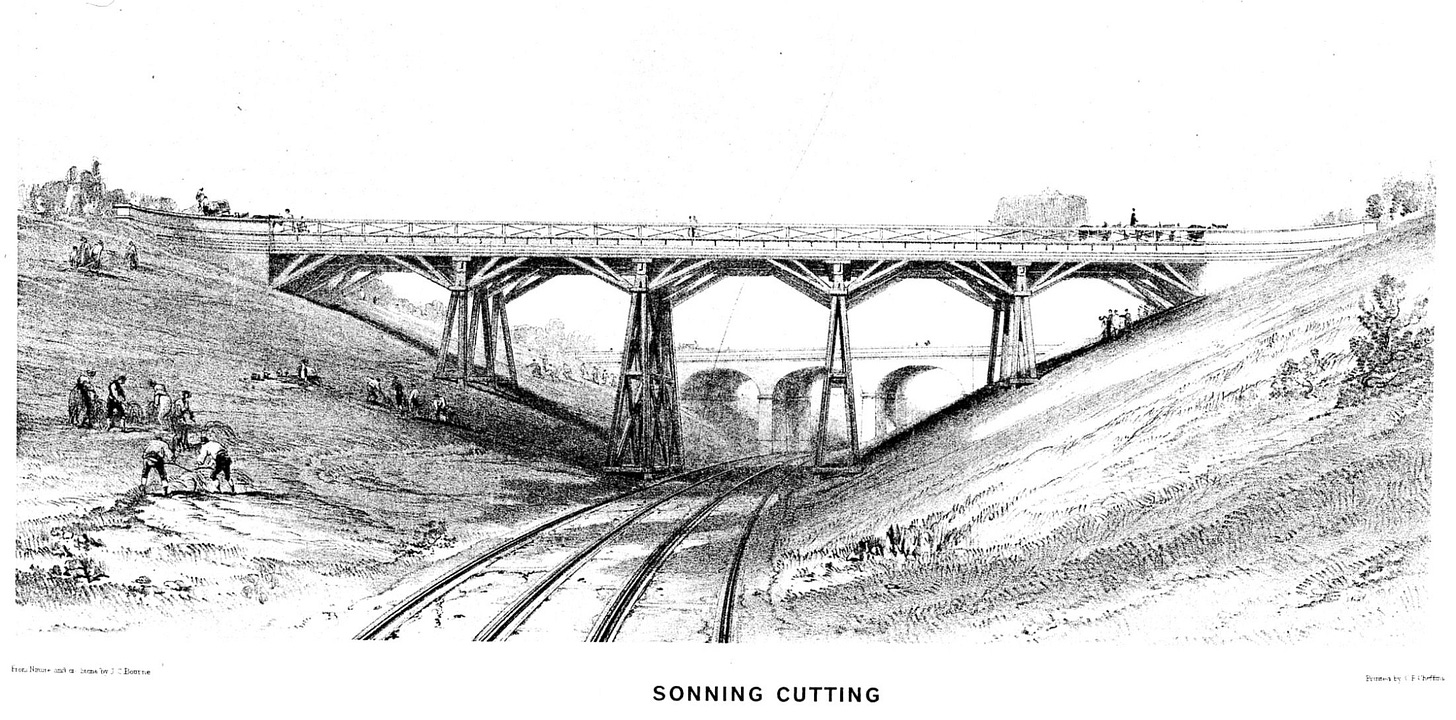

The deodand was only abolished in the nineteenth century, in both English and Australian law. Railway accidents were central to the abolition of the deodand, because nineteenth century coroners and juries tried to use the deodand to deal with the shortcomings of the common law inability to compensate for injury causing death. The final straw was the Sonning Cutting Railway accident in 1841, on the Great Western Railway.

On 24 December 1841, a train consisting of a locomotive, the Hecla; a tender (a carriage carrying fuel for the boiler); three third-class passenger carriages (carrying mainly working men returning from London to their homes for Christmas) and heavily laden goods waggons went through Sonning Cutting, near Reading in Berkshire. Unfortunately, in the early hours of morning before dawn, the train derailed, after it ran into soil which had slipped onto the track at some time in the night, after heavy rains. The passenger carriages were crushed between the tender and the goods waggons; one immediate recommendation was that passenger carriages and heavily laden goods waggons should no longer be coupled together. Eight passengers died at the scene and seventeen were seriously injured, one dying later in hospital, necessitating a second inquest.

At this time, the relatives of the deceased passengers could not sue at common law. A claim in tort died with the victim in whom it vested and did not survive for the benefit of the estate (actio personalis moritur cum persona), even if the tort caused the death. Moreover, the death of a victim was held to cause purely emotional and pure economic loss to their relatives, for which damages could not be recovered.13 This meant that relatives were in a worse position if a victim died immediately as a result of a tort, than if the victim survived but was badly injured. Obviously this situation was unjust.

The solution coroners and juries had developed to deal with these accidents was to deodand the trains which caused the injury and to try to petition the local lord to distribute the proceeds to the families of the deceased. At the two inquests, deodands of £1,100 (equivalent to £134,900 in 202414) in total were made on the train engine and the trucks, payable to the lord of the manor of Sonning. In 1846, the Parliament of England and Wales abolished the deodand and passed Lord Campbell’s Act, to allow relatives of those killed to sue for damages.15 The New South Wales parliament followed suit and abolished the deodand in 1849.16 And so, the legal oddity that was the deodand passed away into history.

Frederick Pollock and Frederic William Maitland, The History of English Law before the time of Edward I (CJ Clay & Sons, 2nd edn, 1898) pp. 473 - 74. The bane would go to the kinsmen of the slain, the owner having “purchased his peace by a surrender of the noxal thing.” Also - recall Isildur’s Bane and Durin’s Bane, from Lord of the Rings! JRR Tolkien, of course, knew his Anglo-Saxons.

Pausanias, Description of Greece, trans. WHS Jones, [6.11.6] - [6.11.9].

Paul J Du Plessis, Borkowski’s Textbook on Roman Law (Oxford University Press, 5th edn, 2020) p. 351. See Institutitones Gai IV 6.75–76; Digesta 9.4.2.1.

Nexum (contracts of debt bondage) were abolished in 326 BCE or 313 BCE.

Du Plessis, above n 3, 351 - 353. Actio de pauperie was described in Institutiones 4.9 and Digesta 9.1.

Stefan Jurasinski, ‘Noxal Surrender, the Deodand, and the Laws of King Alfred’ (2014) 111 Studies in Philology 195. See Exodus 21:29.

The Laws of Alfred, section 13, trans. Frederick Attenborough.

Teresa Sutton, ‘The Nature of the Early Law of Deodand’ (1999) 30 Cambrian Law Review 9, 10.

Anna Pervuhkin, ‘Deodands: A Study in the Creation of Common Law Rules’ (2005) 47 American Journal of Legal History 237.

Sutton, above n 8, 16.

Sutton, ibid, 12 - 13.

Pervuhkin, above n 9, 239, 241–248.

Baker v Bolton (1808) 1 Camp 493, 170 ER 1033.

Result obtained from measuringworth.com, which explains that relative value is difficult to measure. I have taken the “real value”.

Deodands Act 1846 (9 & 10 Vict. c. 62); Fatal Accidents Act 1846 (9 & 10 Vict. c. 93) (‘Lord Campbell’s Act’).

Deodands Abolition Act 1849 (NSW).

Flat bottom boats on the River Ouse and River Thames - which end to punt from :).

Would perhaps be more fun if forfeiture existed… every June there is an email to students along the lines of if you fall in the cam it will likely kill you… (or you should go to A&E).

It is hard to imagine a form of water propulsion than punting… or perhaps I’m just envious because I could never do it

Fabulous article btw!

I wonder of deodand inspired the (bad) American idea of Civil Asset Forfeiture?