On my own merits

Or, the cruelty of pity

I have been disabled since birth, as I have outlined elsewhere, as I was born very prematurely. Luckily, my cerebral palsy is mild: it is mostly from the waist down (apart from my left arm). It is somewhat worse on the left than the right side. When I was a child, I could not hide the fact I was disabled. I walked on tiptoes, with the distinctive scissor gait of someone with cerebral palsy.

When I was thirteen, everything changed—I had what was then an experimental operation, in which my Achilles’ tendons were lengthened—and I could walk in a way approximating normality. I still got teased by people at school: it wasn’t a perfect walk, but it was enough.

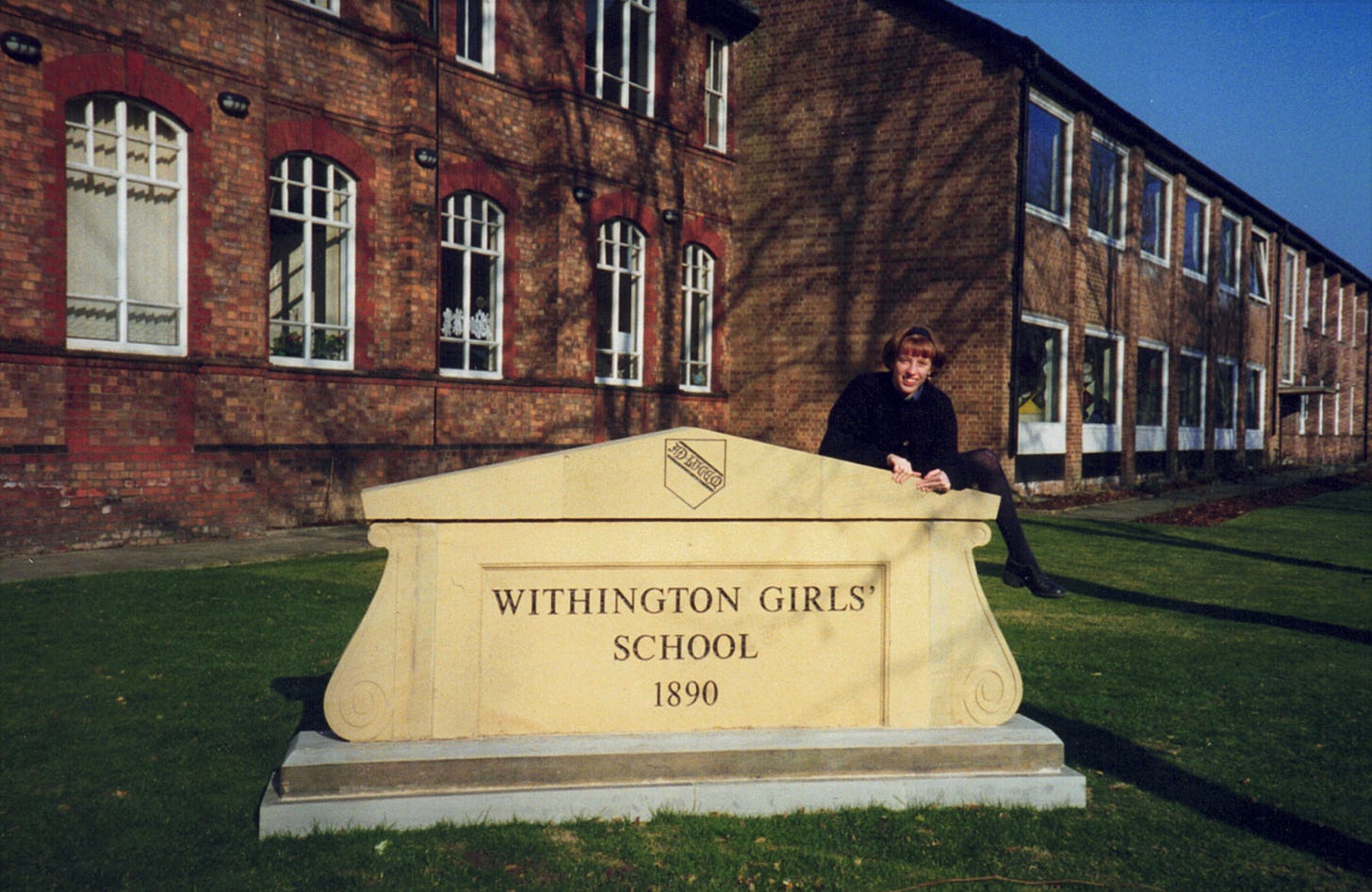

In my mid-teens my family moved to England, and I was sent to a selective private girls’ school in Manchester. I did not tell anyone about my disability. It was then that I discovered something amazing. I could hide my disability. And there were so many other things I could distract the English with—my terrible Australian sense of humour, my disrespect for authority, my difficulty settling into English culture, and my tendency to do very well in exams and assignments.

It was that latter part which convinced them to forgive me for all the rest. Mrs Kenyon, if you’re reading this, I’ll confess: it was I who posted Sarah’s shoes into your office window, simply because she said, “I bet you wouldn’t dare—!” But I think you knew that, and also that I was responsible for several other cheeky incidents.

When I went back to England in 2001, I rang up my headmistress. “Hey Mrs K!”

“Oh, Katy, hello,” said Mrs Kenyon.

“How did you know it was me?” I said. She politely didn’t answer, but I realised in a moment that only one person was going to call up and greet her thus, in a thick Australian accent.

At the end of the conversation she said, “You know, you were very naughty and very ill-disciplined … and we miss you very much. Things have been far less interesting since you left.”

Yep! She knew about the shoes, and likely, several other cheeky, naughty things I did. I almost burst into tears at the encomium! I couldn’t ask for a better one. The hilarious aspect was that by Australian standards, I was a goody two-shoes, and my Australian school reports described an entirely different person.

My English school was the making of me. Why? Simply because they respected my intelligence (even the cheeky parts). I did not have to hide it, and they encouraged it and honed it. I remain so grateful. I was valued for the skills I have.

When I was nineteen, we moved back to Australia, and I went to law school. I did not tell anyone about my disability then, either, other than close friends. It was simply not relevant, and because I could hide it, I did.

I did not mention my disability in job applications or scholarship applications, possibly to my detriment, because I was always judged harshly for my lack of sporting ability.

Once in an interview with an eminent person, I was asked, “What disadvantage have you suffered?” My disability did not occur to me as a possible answer, until years later. I said, entirely honestly, “I consider myself very lucky.” Instead, I discussed the complex difficulties suffered by the Indigenous students whom I had tutored.

I got jobs with the Supreme Court, with law firms, and with Melbourne Law School. I did not mention my disability or any other difficulties I had suffered in any of my applications, or most of my promotion applications. Why? you might ask.

I wanted to be hired and promoted, not for my disability, or for any other minority characteristic I might have, but for my competence and hard work. I wanted to be judged without reference to my individual characteristics. I was lucky that I could pass. I’m fully aware that other people with disabilities or minority statuses do not have this luxury. I could simply be judged as me.

However, in 2017, my walking deteriorated markedly, and by 2018, I could no longer hide my disability: I was using a walking stick, and in constant pain. I had extensive medical treatment and underwent rehabilitation to learn how to walk. It turned out that I had never learned to walk properly. Hence, in my final promotion application (for Professor, in 2018) I had to mention it: the first time in twenty years.

I can also “pass” in other ways. We discovered that Dad’s side of the family has some Indigenous ancestry—confirmed by genetic testing and a variety of other proofs—but this ancestry is not obvious in my looks. I have pale skin, reddish hair and blue eyes, courtesy of my Anglo-Celtic ancestors.

I don’t identify as Indigenous, although I am proud of my Indigenous ancestry, just as I am proud of all the other ancestors (including George Barnett the pickpocket, my first non-Indigenous ancestor to arrive here, transported for theft). They all survived the best they could in a harsh environment.

My ancestors, some of whom looked visibly Indigenous, including my grandfather, did not acknowledge their ancestry. I don’t even know if they knew they had Indigenous ancestry; my childhood recollection is that the Aunties speculated that we had Sephardic Jewish ancestry, explaining the tanned skin. If they did know, it was hidden: a disadvantage which led to discrimination.

The opposite is true now.

When I disclosed the discovery of my Indigenous ancestry to people, I was shocked by the great number of people who said I should now identify as Indigenous to obtain both benefits and grants.

I have never suffered any disadvantage as a result of my Indigenous ancestry. I have never been to Rockhampton, whence my ancestor came. I know nothing about that man, not even his name: simply that he existed, and he was the father of a child called Lucy Emma Brown, born in Rockhampton in 1876, my great-great grandmother. It’s unclear whether Emma’s father came from the local Dharumbal tribe or the Native Mounted Police (who were called in to wipe out the Dharumbal). Perhaps one day I will find out.

I came across this quote from G.K. Chesterton’s Orthodoxy the other day, and it resonated with me:

The modern world is not evil; in some ways the modern world is far too good. It is full of wild and wasted virtues. When a religious scheme is shattered (as Christianity was shattered at the Reformation), it is not merely the vices that are let loose. The vices are, indeed, let loose, and they wander and do damage. But the virtues are let loose also; and the virtues wander more wildly, and the virtues do more terrible damage. The modern world is full of the old Christian virtues gone mad. The virtues have gone mad because they have been isolated from each other and are wandering alone. Thus some scientists care for truth; and their truth is pitiless. Thus some humanitarians only care for pity; and their pity (I am sorry to say) is often untruthful.

Pity can be both cruel and untruthful, says the woman who was, at times, pitied during her childhood. Thank goodness my family never pitied me; they just accepted me for who I am and encouraged me to push myself as much as I could within the constraints I have. Thank you guys, I love you.

Pity is cruel because it makes the subject of pity less a person, and more a vehicle for someone else to prove their righteousness. “Look at me, here I am, being friendly to the spastic girl, am I not kind and good?”

It’s untruthful, because it is not so much about helping the person, but, so it has sometimes seemed to me, more about trumpeting one’s own tolerance and righteousness. I don’t want to get ahead on the basis of being someone else’s pity project.

However, I suspect others in my position might have taken benefits or used tales of disadvantage to get ahead. Sometimes, in bitter moments, I wonder if I was a stiff-necked proud fool not to do so. In other moments, I am relieved: my victories are wholly my own.

The story of my family and our Indigenous ancestry shows vividly that, “You get more of what you subsidise and less of what you tax.” People respond to incentives. When it was disadvantageous to be Indigenous, or descended from convicts, these things were hidden. When it became advantageous, more people started to be open about their minority heritage or identities. That’s not a bad thing, per se. My family shouldn’t have had to hide these things.

But when one’s suitability for a position is simply about signalling one’s minority status and not one’s competence, we have a problem.

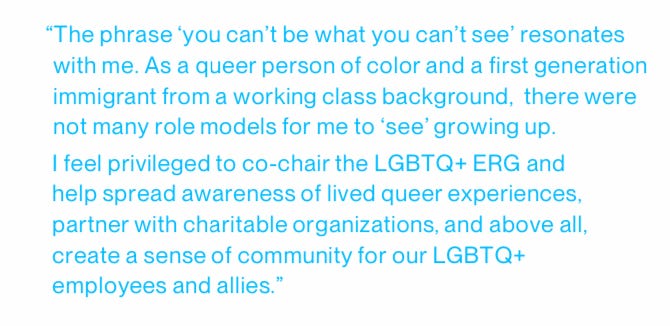

Silicon Valley Bank (‘SVB’) recently collapsed. The former banking and insolvency lawyer in me was fascinated, and so I began trawling through Twitter for commentary and information. It wasn’t long, however, before I came across a Tweet mocking the Head of Financial Risk Management & Model Risk in the UK branch of SVB as a “diversity hire”. SVB’s website includes a document detailing this person’s story in the following terms:

To be fair (and having had experience of this kind of thing) perhaps this person provided a complex story which was reduced to this simple excerpt by a marketing team. I do not wish to cast aspersions. Please note that I have not linked to the Tweet criticising them. I have no idea if they are good or not at their job, and it would be deeply unfair to judge them on an extract from a corporate brochure. I’m happy to see people from minority groups succeed. I don’t care about anyone’s identity, as long as they’re competent and pleasant.

It was, however, notable that this person’s competence and experience in managing risk was not woven into their story. At the very least, this seems to be an instance of the cruelty of pity on the part of SVB. By portraying this person thus, the organisation was trumpeting, “Look how accepting and open we are.” They were not emphasising the person’s competence and ability to do the job, which, it seems to me, is what really matters in any job. This left the person open to being accused of being a “diversity hire”.

I’m clearly not the only person disturbed by this emphasis on disadvantage and minority status, as a recent post by Tanvir Ahmed indicates.

Relatedly, a few years back, a friend rang me after several months in a new job. She was in tears, after it had been disclosed in a meeting that the company had been actively attempting to hire more “people of colour” and was pleased with its progress.

“I thought they hired me because I was good,” she said. “I don’t want to be hired just because I have brown skin!” She considered leaving the company.

Now, I happen to know that this woman is really good. Forget her skin colour, or anything else: she’s a really interesting, intelligent person who performs all aspects of her job well. And fundamentally, that is what matters, as I told her.

In response, she made the point that some might secretly wonder whether she was a “diversity hire”. I explained how I had hidden my disability for this very reason, but noted that she could not hide her skin colour.

In this way, a policy meant to help minorities may actually hinder them, and lead people to make unjustified assumptions about their competence.

In the end, she raised her concerns with the company. They assured her that they valued her. Perhaps they had a wake-up call too: after that meeting, she had applied elsewhere, and received offers from other companies. I told you she was good!

To return to my own tale, my identity must be taken into account in some ways, and it has shaped me. Among other things, I need time off for doctor’s appointments, and I can’t do things other people can do. But I’m glad I could pass for twenty years. It means that I was hired and promoted without regard to my identity, without the fear that beset my friend.

Do you understand now what I mean about the cruelty of pity?

Very well written. I totally agree about the cruelty of pity. It’s cousin might be the bigotry of low expectations (also based on judgements made due to appearance). It’s disgusting.

I have a black friend who was extremely upset when a large group of artists she had joined decided after the George Floyd incident that any BIPOC member of the group would be featured and put forward for special recognition of their art. Her opinion was that she wanted her art to garner attention based on its quality alone. She quit that group!

I've been told to my face, "oh, we know you're competent, you're too old to have been hired just because you're female or lesbian".

The problem of the diversity hire is much, much worse for younger women and ethnic minorities. So many of them are sub-par the rest of us don't know where we stand. It also leads to things like potential employers trawling social media in an attempt to find writing or drafting samples online to see if the woman or ethnic minority has ability (speaking from the point of view of hiring junior lawyers and political staffers, which I've done).