Law French

“Qui ject un brickbat”

I started to write a post on contemporary issues, and then I stopped. Everything is too upsetting at the moment. It seems like division and polarisation between people is everywhere, sometimes in violent and horrendous ways. I can’t write about that right now. It’s too raw.

SO. Let’s talk about Law French instead. Many moons ago, my sister did a French exchange. When her exchange, Melanié, came to visit us, she had a request for me. “Katy, tell me the most complicated English words you can.”

I proceeded to do so. Melanié said, “This is disappointing. These words are very similar to French. I cannot impress people with these.”

I explained to Melanié that English is essentially a creole. At base, it is Germanic, deriving from Anglo-Saxon.1 Therefore a lot of our basic words are Germanic, but all the complex ones are Norman French or Latin (Romance language based).

English was influenced in a variety of ways. From the sixth century AD, missionaries were sent by St Augustine of Canterbury2 to convert the Anglo-Saxons, bringing with them Latin, and so we have Latin loan words. At first, these were mainly to do with the Church and ecclesiastical matters.3

But don’t forget that the Vikings also invaded Britain and Ireland in the eighth to tenth century.4 We have the Norse to thank for the fact that we don’t have those complex Germanic verb conjugations anymore. They couldn’t deal with them, and hence English gradually dropped them. The Norse are also responsible for the sound “sk”, and the sound “th”. “Th” was originally denoted by the letters “thorn” þ or “eth” ð. Both letters, which are still present in Icelandic, remained in English until medieval times. At times, I ðink it might be quite convenient and efficient to keep using ðem. One letter for ðe price of two.

Then—1066 and all that—the Normans invaded and took over England. They imposed their own administration and laws, but left the Anglo-Saxons in place. This meant that the language of court, and the administrative language, was Norman French.5 Meanwhile, the ecclesiastical language and the academic language was Latin.

This means that English is basically Germanic—with the complex declensions eroded by the Norse—with a Romance language overlay and liberal borrowings from almost every other language we come across.

Our complicated words—the legal and administrative words—tend to come from Latin or French. It’s a mashup of different language systems. And that’s why our grammar and spelling is so weird. I do feel sorry for foreigners who have to learn it.

Law has a reputation for being opaque. One reason for this is that the law is conservative: once something is embedded within it, it tended to stay there for quite a while. We have kept words from Norman French which fell out of use in ordinary conversation hundreds of years ago. Do you want to hear some?

Estoppel. Note that this retains the French tendency to start with an ‘e’ where English would start with an ‘s’ (compare école with school). If you take away the ‘e’ the meaning becomes more evident. It means that someone is stopped from asserting a position they had previously taken.

Chattel. I do love this one. It is another word for ‘good’ or movable property. It is related to the word cattle. As I note in Guilty Pigs, “The eighteenth-century judge and jurist Sir William Blackstone noted that both words are derived from catalla, a Latin word that was primarily applied to farm animals, but also to all movable property. In fact in some anxiety societies, and even some modern ones, productive beasts, such as cattle, functioned as currency and status markers.”6

Culprit. The meaning of this is well known—the guilty party—but the legal history behind it might not be. It comes from a scribal abbreviation of the Norman French words used by a prosecutor in opening a trial, namely “Culpable: prest (d'averrer nostre bille)” meaning “guilty, ready (to prove our case)”. The scribes abbreviated this as cul. prit. And hence the word was born!

Laches. In equity, this denotes the bar to relief involving delay with acquiescence or delay with prejudice. It is derived from the Old French word laschesse, meaning dilatoriness or slowness to act. Interestingly, in Modern French, the word lâches means “cowards”: you can see how this might have evolved.

Plaintiff. The fact that this sounds like the word “plaintive” is no coincidence. It means the person who seeks relief from the court, and is derived from the Old French word pleintif, which means complaining.

Replevin. Ooh, this one has a remedial aspect, as well as a restitutionary aspect, so of course I love it. It describes an ancient writ where you can take your personal property back from another, when the other person owes you money. The more general difficulty is that courts presumptively award damages (even to the current day) for torts involving goods and chattels, so if you want your property back, you have to go take it. Another such action is recaption. However, rights to recaption and replevin should be exercised with care.7 You do not want to commit a tort in turn when getting your property back!

Courts used what was called ‘Law French’ right up until the eighteenth century, until the Parliament passed the Proceedings in Courts of Justice Act 1730 (4 Geo. 2. c. 26) to require all court proceedings to be in English.

Law French is a bizarre pidgin: Norman French with English grammar and the occasional random English and Latin word thrown in. I doubt the French would recognise much in it. My favourite instance of Law French—a very famous one—is as follows:

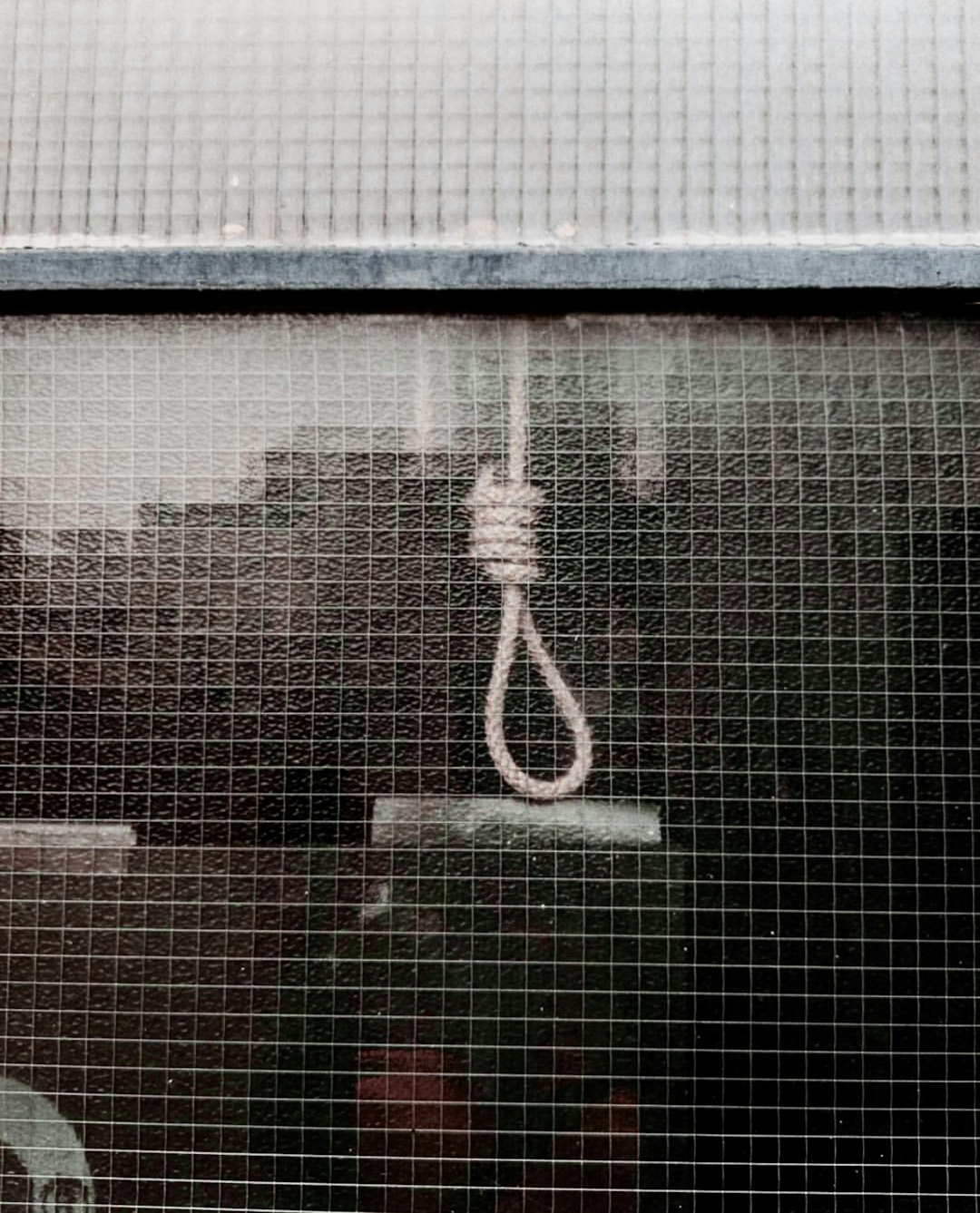

Richardson Chief Justice de Common Banc al assises de Salisbury in Summer 1631 fuit assault per prisoner la condemne pur felony, que puis son condemnation ject un brickbat a le dit justice, que narrowly mist, et pur ceo immediately fuit indictment drawn per Noy envers le prisoner et son dexter manus ampute et fix al gibbet, sur que luy mesme immediatement hange in presence de Court.8

This was a marginal annotation made by Chief Justice Sir George Treby in his copy of Dyer’s Reports, published 1688. Spoiler: it doesn’t end well for the condemned prisoner who threw the brickbat at Richardson CJ. A brickbat, in case you are wondering, is a brick or rock picked up and thrown at a person, but has also come to mean insulting comments hurled at another.

“Narrowly mist” is SO NOT FRENCH, and the spelling of “missed” tickles me particularly.

It didn’t end so well for the prisoner, alas… the moral of the story is to take care throwing your brickbats…

David Crystal, The Cambridge Encyclopaedia of the English Language (2nd edn, Cambridge University Press, 2003) pgs. 6 - 7, 27.

Above n 2, pg. 24.

Ibid, pg. 25. The Viking invasions are why I occasionally get mistaken for being Norse!!! No recent Norse ancestry, just those Vikings.

Ibid, pgs. 30 - 31.

Katy Barnett and Jeremy Gans, Guilty Pigs: the weird and wonderful history of animal law (Latrobe University Press, 2022) pg. 23.

See Katy Barnett and Sirko Harder, Remedies in Australian Private Law (2nd edn, Cambridge University Press, 2018) [13.21] - [13.25].

Translation: “Richardson, Chief Justice of the Common Bench at the Assizes at Salisbury in Summer 1631 was assaulted by a prisoner there condemned for felony, who, following his condemnation, threw a brickbat at the said justice that narrowly missed, and for this, an indictment was immediately drawn by Noy against the prisoner and his right hand was cut off and fastened to the gibbet, on which he himself was immediately hanged in the presence of the Court.”

I love this article. Absolutely fascinating. I had no idea of the history!