Jumping off the judicial ship

Two overseas judges on the Hong Kong Court of Final Appeal quit

It is difficult to know when to jump from a sinking ship. Usually there are still many good people on the ship, people who are deserving of support, and if you jump, you feel like you are abandoning them. Can the ship still be righted? Can you make a difference? This past fortnight, I have been thinking a lot about Hong Kong, now a Special Administrative Region of the People’s Republic of China, particularly after I saw that two retired English judges, Lord Collins and Lord Sumption, had resigned from the Hong Kong Court of Final Appeal, where they had been sitting as non-permanent judges.

This leaves eight overseas non-permanent judges (three English, one Canadian, and four Australians). Justice McLachlin, the esteemed Canadian judge, said in May 2024 that she will not renew her term once it comes to an end in July 2024: then there were seven.

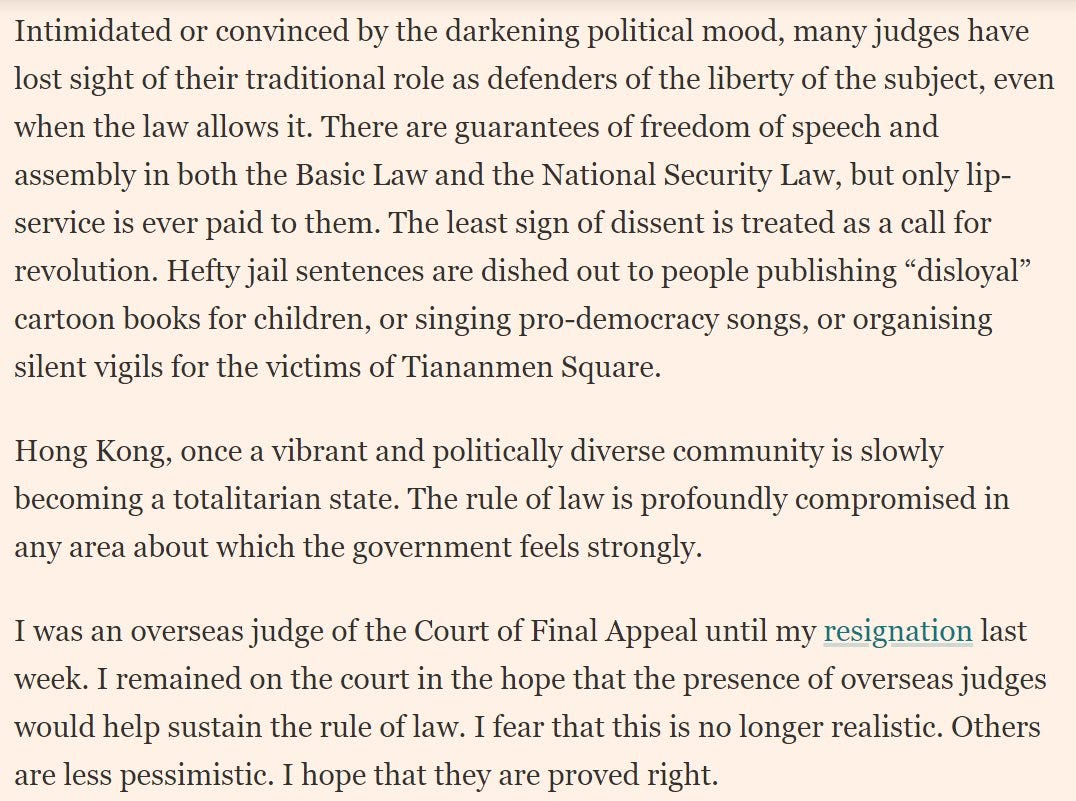

Lord Sumption’s statement about why he stepped down was published in the Financial Times. He doesn’t pull any punches. The conclusion to his statement is below:

Unsurprisingly, the Hong Kong SAR government issued a rebuttal of Lord Sumption’s assertions.

I became aware, upon discussing the issue with friends, that people were not necessarily aware of the recent legal changes in Hong Kong. My intention with this post is simply to explain why Lord Sumption may have come to the view that he did.

I start with the observation that things changed drastically in 2019, when the Hong Kong SAR government proposed amendments to extradition laws with the Fugitive Offenders and Mutual Legal Assistance in Criminal Matters Legislation (Amendment) Bill 2019, allowing for extradition of criminals to China, Taiwan and Macau. This sparked massive protests. The bill was withdrawn in October 2019.

In response to the protests, the National People’s Congress Standing Committee of the People’s Republic of China passed the Law of the People’s Republic of China on Safeguarding National Security in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (colloquially known as the ‘National Security Law’). The National Security Law established four crimes: secession, subversion, terrorism, and collusion with foreign organisations. It is noteworthy that this took place during the global COVID epidemic.

The 2020 legal changes were not the first time national security legislation had been mooted: a previous attempt to pass such legislation had been made in 2003 by the Hong Kong SAR government, pursuant to Art 23 of the Basic Law, during the SARS epidemic, but half a million people marched through downtown Hong Kong in protest, and the legislation did not pass.

The 2020 legislation differed from the 2003 legislation in several regards, and not only because it was passed by the National People’s Congress, rather than the Hong Kong SAR legislature. First, police are authorised to search without a warrant (a power that had been removed in the 2003 bill after pressure). Secondly, the crime of secession is defined more broadly as including acts which undermine national unification “whether or not by force or threat of force”. Thirdly, the 2020 law covers anyone in Hong Kong, regardless of nationality or residency status, but also applies to offences committed outside Hong Kong by a person who is not a permanent resident (keep that in mind). In the 2003 legislation, subversion and secession were limited to Hong Kong permanent residents, and treason was limited to Chinese nationals, regardless of where the crime was committed. Fourthly, the penalties include life imprisonment, and trial is by judge, not by jury, despite Hong Kong’s long common law history. Only “designated judges” may hear National Security Law cases, according to Art 44(3) of the National Security Law.

Subsequently, the Safeguarding National Security Ordinance 2024 has been passed by the Hong Kong SAR and took effect on 23 March 2024. This was made by the Hong Kong SAR legislature, pursuant to Art 23 of the Basic Law. This has strengthened surveillance powers and penalties for offences such as treason and insurrection.

Numerous arrests and convictions of pro-democracy advocates have taken place since the National Security Law came into force in 2020, and bounties have been placed on the heads of others who are overseas, including two Australian citizens, Ted Hui and Kevin Yam. Seemingly, from the timing of it, the straw which broke the camel’s back and prompted the resignation of Lord Collins and Lord Sumption from the Hong Kong Court of Final Appeal was the prosecution of “the Hong Kong 47”, a group of pro-democracy activists, including politicians, journalists, a former law academic and others under the National Security Law.

HKSAR v Ng & Ors was handed down on 30 May 2024.1 Forty-five of the forty-seven defendants were found guilty of National Security Law offences, for conspiring to block government budgetary supply; the government is appealing the finding of not guilty for the two district councillors who were acquitted. The first defendant, Mr Gordon Ng, is a dual citizen of Hong Kong and Australia, prompting the Australian government to raise concerns about the case. The People’s Republic of China responded that it did not recognise dual nationality, and as far as it was concerned, Mr Ng is a citizen of China only.

What then of the Australian judges? The list of overseas non-permanent judges is starting to look rather lean, particularly given McLachlin J’s imminent departure.

For now, Australian judges are staying put, with at least one Australian judge, Justice Keane, defending the Hong Kong judiciary, notwithstanding the concerns raised by Lord Sumption.

The case of HKSAR v Chow Hang Tung shows that perhaps, non-permanent judges can have some alleviating effect, although it also underlines the limits of what judges can do more generally.2 Ms Chow is a former barrister, human rights lawyer, and an advocate for democracy in both Hong Kong SAR and Mainland China. She is currently imprisoned in Hong Kong for “incitement to subversion” under the National Security Law.

The events which led to Ms Chow’s imprisonment arose from her position as the Vice Chairman of the Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements of China. In May 2021, as required by ss 7(1)(a) and 8 of the Public Order Ordinance, she notified the Commissioner of Police of the Alliance’s intention to hold a meeting at Victoria Park between 8 pm and midnight on 4 June 2021 to commemorate the 32nd anniversary of what Cheung CJ calls the “4 June incident”.3 In response to police concerns, the Alliance undertook to revise the number of protesters down, and to shorten the protest to two hours. However, it was to no avail. As Cheung CJ explains at [4]:

On 27 May 2021, the Commissioner of Police issued a notice of prohibition to the Alliance pursuant to section 9 of the Ordinance, prohibiting the holding of the meeting on 4 June 2021. The notice stated that in view of the need of maintaining public safety, public order and protecting the rights and freedoms of others, and after taking into account local and global Covid pandemic situations at the time, the Commissioner had decided to prohibit the intended meeting.

Ms Chow has been in a maximum security prison since September 2021. On 13 December 2021, Ms Chow was sentenced to 12 months in prison because she took part in a 4 June vigil in 2020. On 4 January 2022, Ms Chow was sentenced to prison for further 15 months over the 2021 vigil discussed in this case, with 10 months of the sentence to be served consecutively with the December sentence (a total of 22 months). She appealed against that decision successfully, on the basis that the Prohibition Order issued on 27 May 2021 had not been lawfully issued. Specifically, s 9(4) of the Ordinance required the police to undertake an exercise in “operational proportionality” and Ms Chow argued that the police had not seriously undertaken such a consideration. Barnes J of the High Court of Hong Kong quashed her conviction,4 saying at [64]:

Taking all the above into consideration, it is my view that the evidence did not show that the police had discharged their positive duty under section 9(4) of the Public Order Ordinance by considering that apart from the ban, whether there were other feasible measures which would permit and facilitate the holding of the meeting. Both the Appeal Board and the trial magistrate accepted the pandemic consideration to be the reason for issuing the Prohibition Order, but they also did not take into account the feasibility of other measures or conditions. Therefore, the respondent has failed to establish the legality of the Prohibition Order, and I find that the challenge by the appellant succeeds.

The Hong Kong SAR government then appealed that decision to the Hong Kong Court of Final Appeal. While the appeal was unanimously allowed on 25 January 2024, and Ms Chow’s conviction was upheld, the reasoning of the Court of Final Appeal differed. Two of the judges (Cheung CJ and Lam PJ) found that Ms Chow was not entitled to challenge the legality of the Prohibition Order. Three of the judges (Ribeiro PJ, Fok PJ and Gleeson NPJ) found that Ms Chow was entitled to challenge the legality of the Prohibition Order. They nonetheless allowed the appeal because, in the context of the COVID pandemic, they found that the Prohibition Order was a proportionate measure and represented a fair balance between the restriction on the right of peaceful assembly and the societal benefits of the prohibition. Absent the presence of the COVID pandemic, the decision might have been different. Gleeson NPJ, of course, is the former Chief Justice of the High Court of Australia, although he has now retired from the Court of Final Appeal. Hence one can see why non-permanent judges may feel it is important to remain.

On that point, it is noteworthy that the National Security Laws were first proposed in 2003, during the SARS epidemic in Hong Kong, and successfully implemented seventeen years later, during the height of the global COVID pandemic. In my home State of Victoria, I personally bore witness to the extent to which concern for public health can potentially override civil liberties, notwithstanding the presence of a Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities in Victoria. This is a balancing act which must always be struck carefully; I believe we can learn lessons from incidents in which authorities overstepped the mark, in any jurisdiction.

Meanwhile, Ms Chow remains in a maximum security prison. She faces further charges of “incitement to subversion”, and, in May 2024, has just been charged with further offences of sedition in relation to Facebook posts which mention a “sensitive date”.

Kevin Yam is an Australian lawyer and citizen who lived in Hong Kong for over 20 years and was also involved in pro-democracy movements while he lived there. I’m proud to say that he’s a friend of mine, since our first week of law school. In July 2023, he had a HK$1million bounty placed on his head, after allegedly breaching the National Security Law as a result of statements he made on Australian soil as an Australian citizen, regarding the situation in Hong Kong SAR. In The Australian he had this to say about the situation of the Hong Kong Court of Final Appeal:

Australian judges tried valiantly in recent years to make a difference during the post-Hong Kong crackdown, but its victories have been Pyrrhic. Their continuation on the court is against the backdrop of Australians being viciously persecuted by China and Hong Kong authorities. I believe the Australian judges have every reason to follow the leads of Sumption and Collins and resign from the HKCFA.

I nonetheless admire these Australian judges. They are trying to serve Hong Kong in difficult circumstances, for which I am grateful. I am therefore appalled by, and reject, grubby allegations that they remain on in Hong Kong for the money. They have all had long and successful careers, and in any event can earn much more and with less reputational risk by acting as commercial arbitrators and mediators.

I hope these Australian judges will eventually agree with me. But if they do not, then count my views as, in legal speak, a dissenting opinion.

I, too, understand why judges would not want to jump from a sinking ship. I have a perennial desire to help people. Nonetheless, if I were an overseas non-permanent judge on the Hong Kong Court of Final Appeal, I would have made the same decision as Lords Collins and Sumption. I hope this post gives some understanding of why I have that view.

Ibid, [2]. While in China, this event is known as the “June Fourth Incident”, in the West this is better known as the “Tiananmen Square Massacre”. On 4 June 1989, the Chinese army was deployed to clear Chinese pro-democracy protesters (predominantly students) in Tiananmen Square. It is unclear how many people were killed.

A good article.

One typo: 2003 vs 2020, you meant seventeen years later, rather than seven.

All of us have a muddled sense of passage of time due to the two years of lockdowns, and the years before blur together.