Getting away with murder

The strange case of “want of evidence”

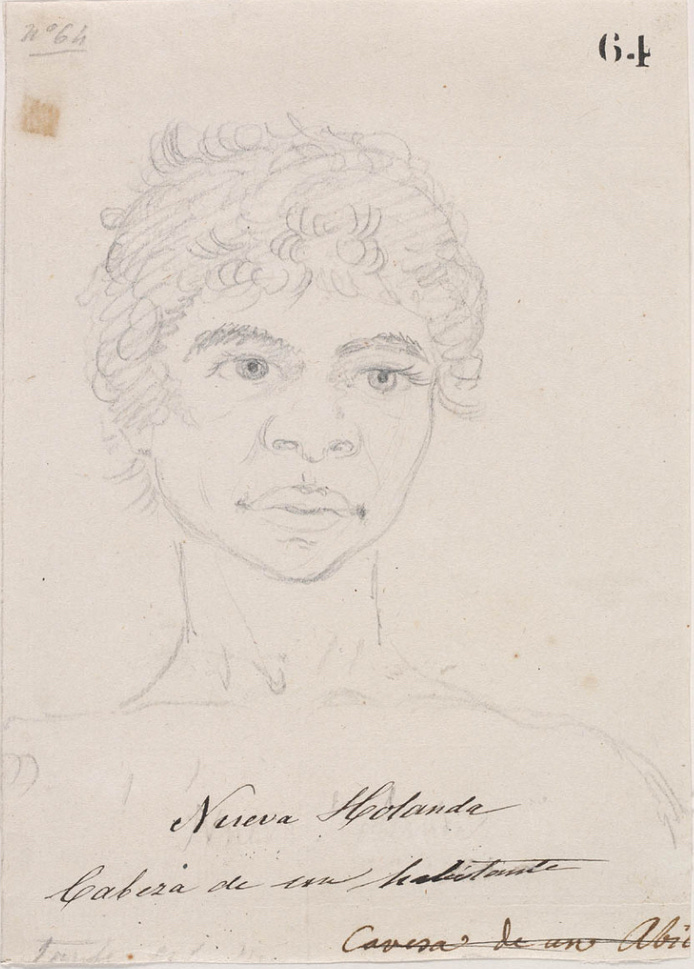

[Warning: this post contains a drawing of a long-dead unnamed Indigenous boy and discusses settler-Indigenous conflict in early colonial Australia.]

I stumbled across a strange and terrible legal case the other day. I was researching the complexity of Indigenous-settler relationships, in the context of my own family history. On my mother’s side, my putative great-great-great-great grandfather, Thomas Rowley, was a captain and then an adjutant in the New South Wales Corps.1

Captain Rowley was evidently an impressive or pleasant person, because an Indigenous man living in Sydney was named “Tom Rowley” in tribute to him. His respectful attitude towards Indigenous people seems to have been passed on to at least one of his sons.2 I decided to research how Tom Rowley came to take Captain Rowley’s name. It’s unclear, but seems that Tom Rowley might have been one of several Indigenous orphans, adopted by settlers and given English names (along with Bondel or “Bundle”, Tristan Maamby and James Bath). He was an enterprising and adventurous man who sailed on the whaler Britannia to Calcutta (Kolkata) and Madras (Chennai) and New Ireland in 1795, returning to Australia in 1796.

Alas, the story does not have a happy ending. In 1797, Tom Rowley was shot in the thigh on the Hawkesbury River, by a European settler named William Millar, who was aided and abetted by another man named Thomas Bevan, and Tom Rowley died of his wounds shortly afterwards.

After Tom Rowley’s death, Governor Hunter decided that everyone in the colony was under the equal protection of the law, including Indigenous people, and that Millar and Bevan should be put on trial. The details in R v Millar and Bevan3 are scant:

William Millar and Thomas Bevan were brought before the court for that they not having the fear of God before their eyes but being moved and seduced by the instigation of the Devil on or about the sixth day of October in the thirty fourth year of the reign of our Sovereign Lord George the Third now King of Great Britain etc. with force and arms on the north-shore in county aforesaid in and upon a native commonly known by the name of Tom Rowley in the peace of God and our said Lord the King then and there being feloniously, willfully and of their malice aforethought did make an assault.

Judge Advocate Richard Atkins of the Court of Criminal Jurisdiction acquitted the men for “want of evidence”. I knew that Atkins was known for his poor legal knowledge,4 irresolution, drunkenness and failure to pay debts. However, I had never heard of acquittal for “want of evidence” before. I decided to find out what it meant.5

The only witnesses to Tom Rowley’s death—other than Millar and Bevan themselves—were other Indigenous people. R v Millar and Bevan was the genesis of a line of Australian legal authority which held that Indigenous people were not competent to give evidence.6

The reasons for this were more complex than I anticipated. The trustworthiness of evidence is difficult to assess (hence, trial by ordeal and trial by combat in earlier times as ways of testing veracity). It was decided by medieval canon lawyers that evidence would be reliable only when the witness understood the dire religious consequences of lying. These principles were drawn into the English common law, via the rules governing the competence of jurors, and filtered into the development of laws of who could give evidence in 16th and 17th centuries.7

As a result, English common law in the 18th and 19th century provided that witnesses could only give evidence if they understood that if they lied on oath, they would be subject to the Divine Retribution of God. A child’s evidence was only acceptable if the child understood that oaths were punishable by damnation.8 The same rule was applied to non-Christians.9 There was some leeway, but a belief in divine punishment was essential. Hence it was stated in Omychund v Barker, a case involving a Hindu merchant:10

Though I have shewn that an Infidel in general cannot be excluded from being a witness, and though I am of opinion that Infidels who believe a God, and future rewards and punishments in the other world, may be witnesses; yet I am as clearly of opinion, that if they do not believe a God, or future rewards and punishments, they ought not to be admitted as witnesses.

In R v Millar and Bevan, the Indigenous witnesses to Tom Rowley’s death (very reasonably) did not understand translated questions about the Divine Retribution of God and the existence of Hell. Judge Advocate Atkins therefore ruled that their evidence was inadmissible. “Acquitted for want of evidence” means that no Indigenous witness could challenge Millar’s testimony that he had not possessed “malice aforethought”.

Later, when frontier violence between Indigenous people and settlers intensified (from 1799 to around 1810) Governor Gidley King sought Atkins’ advice on whether Indigenous people who’d killed European settlers could be prosecuted in turn. In an 1805 advice entitled ‘Opinion of the Treatment of Natives’, Atkins held that they could not, because “the Evidence of persons not bound by any moral or religious Tye can never be construed as legal evidence.”11

Indigenous people and non-Christians were not the only people whose evidence was deemed inadmissible in colonial society. There was a blanket rule against admitting evidence of lunatics, convicts and accused criminals because they were thought to be intrinsically untrustworthy.

In R v Hatherly and Jackie,12 Atkins’s 1805 advice was followed, and two Indigenous men were acquitted of the murder of a settler named John McDonald, although they’d confessed. The court held that they were not guilty, because “under all the peculiar circumstances of the case as there existed no other proof against the prisoners than their own declaration, which could not legally, in this instance, be construed into a confession... .”

As Salter has noted, the net effect of these rules was to ensure that the developing Australian law ignored Indigenous people and their concerns:

Settler-Indigenous violence was dealt with outside the formalities of the colonial courts through acts of violent retaliation and settler-Indigenous diplomatic negotiation. In the very few instances that a matter of settler-Indigenous violence made it to trial, a settler authority continued to prevail. Usually framed in the form of a rudimentary self-defence or provocation plea, evidence of the imminent threat of Indigenous violence, or retaliation against violence, would often be successfully invoked by settlers to justify their own acts of violence. The proceedings in Hatherly and Jackie illustrate the complexities and contradictions of the earliest Indigenous interactions with settler courts. Despite Hatherly and Jackie being acquitted for the murder of John McDonald, the proceedings profoundly demonstrate how Indigenous people had little or no influence in the way that the law of the new colony would be shaped.13

Would the admission of evidence by Indigenous people have made a difference to unfolding conflict? Would Indigenous people have been able to put their own perspective, and be heard by the courts and the settlers? It is impossible to know. Later Acts allowing for admission of Indigenous evidence were well-intentioned but did not solve the problem; instead the legislation had unintended negative consequences.14

In some instances, settlers were punished for murdering Aboriginal people. The first such case is R v Kirby and Thompson,15 in 1820. John Kirby was executed for the murder of an Indigenous elder named Burragong (also known as ‘King Jack’) described by the court as a “kind, useful, and intelligent elder”. Although the circumstances in R v Kirby and Thompson were very similar to the earlier case of R v Powell,16 the different treatment of the two cases seems to stem from the fact that Kirby was a convict, and Burragong was an elder and an ally of the colonists.17

Conversely, in R v Powell, the alleged murderers were a constable and four free settlers, and the two murdered Indigenous men were young and were reported to have threatened another Indigenous man and European settlers. Even then, the Court of Criminal Judicature split 4 to 3 on the question of whether they should be acquitted.

Later, in 1838, settlers perpetrated the notorious Myall Creek Massacre of (at least) twenty-eight unarmed Indigenous people, including women, children and babies. Seven out of the twelve of accused murderers were eventually convicted, after two trials,18 although the ringleader of the massacre evaded arrest and was never prosecuted. A European settler named George Anderson, the station hut-keeper, gave evidence for the prosecution. The judge said that there was no excuse or provocation for the massacre when he handed down sentence (warning, the description of the crime is horrific). Governor Gipps refused to extend clemency to the seven convicted men, and they were hanged.

Unfortunately, the conviction and execution of the Myall Creek Massacre perpetrators generated outrage at that time, with many settlers considering the murders were justified, that the Indigenous victims were less than human, and that Indigenous people should be exterminated because they were a threat to life and property. Many (although not all) of the newspaper editorials and opinions of the time are hair-raisingly terrible.

I wish I could say that I can’t imagine educated people in the current day celebrating the death of innocent men, women and children, but alas it still happens, as demonstrated by some social media responses to recent global atrocities.

Eventually, in 1876 (after several attempts in 1839, 1841 and 1844) legislation was passed to allow witnesses in New South Wales (including Indigenous witnesses) to give evidence without the need to swear a Christian oath.19 On my father’s side, one of my great-great-great grandfathers was an Indigenous man from Rockhampton. I couldn’t help thinking about him when I did this research.

The death of innocent civilians of any background or nationality will always be a tragedy, whenever and however it occurs. Moreover, we depart from the rule of law at our peril, as Tom Rowley’s tragic tale indicates.

In fact, he turned out not to be my true forebear, according to ancestry tests. The real father of my ancestor Eliza Rowley, fifth child of Betsey Rowley, was the former convict Simeon Lord, as we have been matched with numerous descendants of Lord.

Thomas Rowley’s second son, John Rowley, was responsible for recording the language of the Gamilaroi people around St George’s River and Cowpastures, and promoted charities to help Indigenous people. He may have been influenced not only by his father, but by Charles Throsby, whom he accompanied on his explorations. Throsby was comparatively enlightened for those times because he believed that the indiscriminate slaughter of Indigenous people would bring only revenge and that it was possible to live in harmony with them.

[1797] NSWSupC 3; [1797] NSWKR 3 (10 October 1797).

There were no non-convict lawyers in the colony. Atkins relied very heavily on the assistance of George Crossley, a convict lawyer transported for perjury. The Court of Criminal Jurisdiction therefore consisted of the Judge Advocate (a lay judge) and six New South Wales Corps officers (on a rotating basis).

Brent Salter, ‘‘For Want of Evidence’: Initial Impressions of Indigenous Exchanges with the First Colonial Superior Courts of Australia’ (2008) 27(3) University of Tasmania Law Review 145.

R v Millar and Bevan [1797] NSWSupC 3; [1797] NSWKR 3 (10 October 1797); R v Hewitt [1799] NSWSupC 2; [1799] NSWKR 2 (1 February 1799); R v Powell and others [1799] NSWSupC 7; [1799] NSWKR 7 (16 October 1799); R v Luttrell [1810] NSWSupC 1; [1810] NSWKR 1 (13 March 1810).

William Holdsworth, A History of English Law (Methuen & Co Ltd, 3rd edn, 1944) 185 - 203.

R v Brasier (1779) 1 Leach 199; 168 ER 202.

Maden v Catanach (1861) 7 H & N 360; 158 ER 512.

Omychund v Barker (1744) 1 Atk 21, 45; 26 ER 15, 31 (also reported as Omichund v Barker (1744) Willes 538; 125 ER 1310).

Richard Atkins, ‘Opinion on Treatment to be Adopted towards the Natives’, 20 July 1805, Historical Records of Australia, Series 1, Vol 5, pgs 502 - 504.

[1822] NSWSupC 10; [1822] NSWKR 10 (27 December 1822). Salter queries the veracity of the ‘confessions’ Brent Salter, ‘Case Note: Coming Clean in the Colonial Courts: the 1822 ‘Confession’ of Hatherly and Jackie’ (2009) 14(1) Deakin Law Review 125

Salter, above n 4, 160.

See eg, Aboriginal Witnesses Act 1844 (SA) which was intended to allow Indigenous people to give unsworn evidence, but because it gave discretion to judges as to the weight to be accorded to the evidence, did not apply to cases involving capital punishment, and required corroboration of a non-Indigenous person in criminal cases, it had the opposite effect of what was intended.

[1820] NSWSupC 11; [1820] NSWKR 11 (14 December 1820).

[1799] NSWSupC 7; [1799] NSWKR 7 (16 October 1799).

Salter, above n 4, 150 - 151.

R v Kilmeister (No 1) [1838] NSWSupC 105 (15 November 1838); R v Kilmeister (No 2) [1838] NSWSupC 110 (26 November 1838); R v Kilmeister (No 2) [1838] NSWSupC 110 (5 December 1838).

Evidence Act 1876 (NSW), s 3.

Very interesting history. Thank you for taking the time to write.