Cancelling “cancel culture”?

Is it possible? Maybe - but it would be complex…

I see that Singapore is considering enacting laws to combat “cancel culture”. I don’t know precisely what’s provoked this, but I suspect that the government of Singapore is concerned that social media is destroying the ability of societies to tolerate disagreement.

Before I get into the legal complexities this might raise, I take “cancel culture” to mean the phenomenon where an individual expresses contentious views that others on social media find offensive.

People who find the views offensive vocally express outrage, sometimes towards the individual, often more widely, on social media. He or she becomes “Twitter’s main character” for a time. The individual’s employer then takes action. If the person is sacked, or is otherwise forced to resign—and cannot get another job elsewhere because of the way in which their reputation has been undermined—they are “cancelled”.

First, some ground-clearing. I do not intend to get into debates about whether cancel culture “really exists”. Of course it exists. I suspect it’s existed since before we were modern humans. It’s a recognised way in which humans try to enforce group norms: if you stray too far from the path of what the group thinks is acceptable, you’re exiled, ostracised, or even killed.

I also do not intend to get into arguments about whether the left or the right are worse cancellers. My view is that it fluctuates, depending upon the norms held by those who currently command the cultural heights in a particular society, place or institution, or even on the norms which apply in a particular situation.

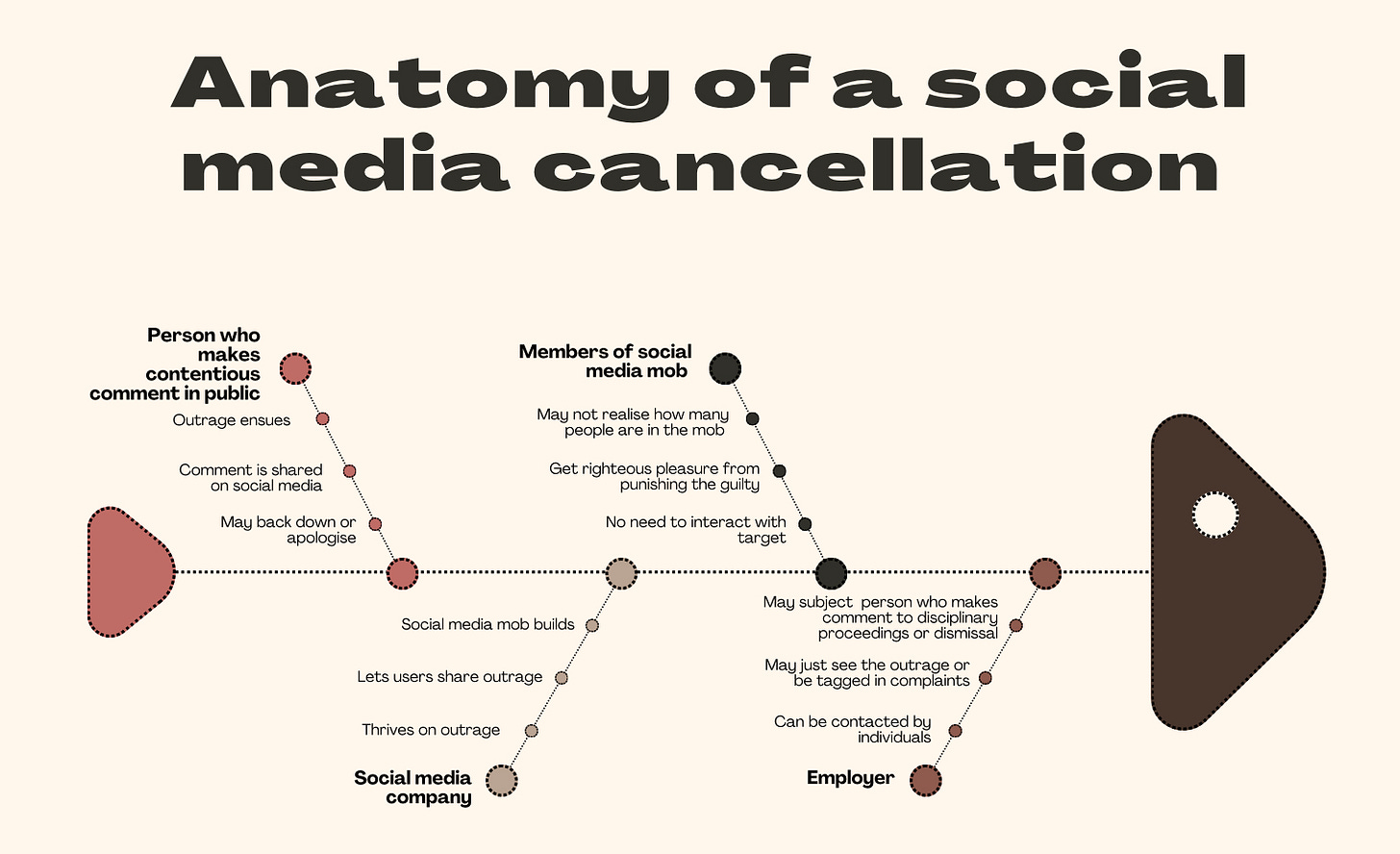

There are multiple participants in a cancellation. I’ve attempted to illustrate them with the diagram above. I hope it shows clearly why social media cancellation will be difficult to prevent with legislation. You can’t just simply say to the social media mob, “Hey, this is illegal, you have to stop it.” In fact, as I’ll outline, sometimes, the mob may have a point.

The four players are:

The person who makes the contentious comment in public;

The social media company or companies which allow the comment to be shared, and then allow others to attack the maker of the comment;

The members of the social media mob who attack the person who makes the contentious comment; and

The employer of the person who makes the social media comment.

As always, we need to look at the present incentives, because this will shape the legal response and its success. Let’s look at each of the players more closely.

The person who makes the contentious comment

There are significant legal, financial and social disincentives to make public comments which some might find offensive or controversial.

In Australia, multiple laws might have an impact. First, the torts of defamation and injurious falsehood can make someone liable for false statements regarding individuals and businesses respectively. Secondly, provisions such as s 18C of the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth) prohibit people from making public statements regarding another’s race, colour or national or ethnic origin, if it’s likely offend, insult, humiliate or intimidate. Thirdly, we have provisions such as s 18 of the Australian Consumer Law, which seek to prevent misleading or deceptive conduct in trade or commerce.

From a practical point of view, even if it’s not illegal to express a certain view, a careless social media post might cost a person their reputation, friendships, and employment, and it might be difficult to find employment afterwards.

This can be particularly devastating if you’re in a creative industry. If you act in movies, record songs, or write books, your continued participation in the industry is predicated upon getting others to accept and promote each successive work.

Many people may think it’s a good thing that people are more wary of making potentially offensive comments in public. This is not surprising from an evolutionary perspective. As Will Storr has outlined in The Status Game: On Social Position and How Use It, one of the ways in which humans gain status in groups is through virtue, by convincing others that they are worthy by demonstrating belief or behaviour which serves group interests, and decrying the non-virtuous.

Humans are a social species, and we’ve been living together in tribes for hundreds of thousands of years. We’ve evolved to think it’s a good idea to stop people from making comments which might cause fights within our group, in part because one of the other ways we gain status in social groups is through dominance, namely, by forcing others to respect our status by brute force.1

If you’re squeamish about that notion, that’s also understandable from an evolutionary perspective. There’s some evidence that humans banded together to kill off “alpha male” leaders, which is why we don’t have alpha leaders like chimpanzees do.2

There are situations where we want people to adhere to social norms, and to lose their jobs if they don’t. An example I’ve used before is the incident where a Victorian police assistant commissioner was forced to resign, after it was revealed he had made racist and sexist comments online under a pseudonym, even targeting his colleagues and the commissioner. He was the head of the police’s ethical standards body, and his online comments demonstrated that he was not a fit and proper person for the job.

But there are other situations where it’s not clear that the contentious view expressed affects the person’s ability to do the job. That’s when it gets difficult.

Social media brings together people with wildly different ideas about appropriate norms, and wildly different values and upbringing. Previously, these people would have been unlikely to have come in contact. Now, they rub up against each other thanks to the marvels of technology. Social media also blurs the distinction between the public and the private. Offhand statements which would have previously been made to a mate in the pub, coffee shop, or drinking venue of your choice are now reduced to writing and visible to the multitudes.

Relatedly, another difficulty is that the standards of what is and isn’t offensive aren’t subject to agreement. You may be wildly offended by something that I find inoffensive, or vice versa. What’s regarded as offensive has also changed radically over the last thirty years.

A group can always go overboard and become a mob. Lynchings, witch-hunts, vigilanteism are all examples of when our desire to police behaviour we regard as offensive or dangerous to our society goes very badly wrong, and leads to great injustice. I’ve argued before that allowing too much “self-help”—giving the mob too much free rein—can undermine civil society. When someone says something offensive, I think the best course of action is to step back, and let the outrage flow away, before we do anything. There may be circumstances where someone needs to leave their employment, but it should be a decision taken with a cool head, not a decision made in fear or anger.

The social media company

Social media companies have few reasons to stop people from making contentious comments, and no reason to prevent social media mobs from occurring; indeed quite the opposite. Their business model thrives on outrage. The reason why there’s no incentive to change is because, in the 1990s, legislation was passed in the United States to facilitate the development of the Internet, including §230(c)(1) of the Communications Decency Act 1996 (US), which states:

(1) Treatment of publisher or speaker No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider.

This means that under United States law, a social media platform provider is immune from liability if they publish information provided by third-party users which causes harm to another.

To be honest, I think it will be difficult to shift online culture, unless social media providers are made liable for the behaviour of those who use their services.

This would end the Internet as we know it, as social media providers and others would finish up with a status similar to publishers of newspapers, magazines and books. This may return us to pre-social media norms, but there’s always the risk that any new cultural “gatekeepers” are worse than the mob—or even made up of the mobsters.

The members of a social media mob

There is little legal incentive upon those who join the social media mob not to take part, unless of course, they are saying something defamatory (a false statement which would tend to bring the victim into disrepute), or bring a business into disrepute with the tort of injurious falsehood.

Part of the issue for a member of a mob is that they may not even realise they are part of a mob. They might see the contentious statement, type something to the person who made it, and not realise that one thousand other people around the globe are simultaneously piling on the person who made the statement too.3 It’s easy to become a keyboard warrior, and forget that there’s a real person at the other end. I suspect people say things online that they’d never say to someone’s face.

My rule of thumb is to always presume that everything I say will be seen by a judge, so I’d better be careful with what I put in writing. Once a litigator, always a litigator, even if I’m now a lecturer. As the rhyme goes, if you’re unsure, “Say it with roses, say it with mink, but never ever say it in ink.” For this reason I also keep away from social media if I’m tiddly.4

I have wondered previously if some of the other economic torts could be repurposed to make people more wary of attacking others online, and more wary of calling for someone to be sacked. Such torts include inducing breach of contract (which I discussed recently) but I’m not aware of them being repurposed in this way in Australia.

In the US, the economic torts have been used against in-person protesters, most famously in Gibsons Bros., Inc. v. Oberlin College,5 where a university was made to pay US$36.59 million damages to a bakery by the Ohio Court of Appeals, after it was found that they had participated in libel (defamation via written statements), tortious interference with business, and infliction of emotional distress.

The case arose after three black students were arrested for shoplifting from the bakery in 2016, charges to which they ultimately pled guilty. Students and staff of the university participated in rallies, protests and boycotts of the bakery, alleging that the bakery owners and staff were racist and regularly racially profiled customers. Importantly, university staff distributed flyers which made false accusations against the bakery, and the student senate’s resolutions making these accusations were posted publicly at the university and emailed to all students.

Of course, the success of using economic torts as a disincentive depends upon (1) the individual whose reputation has been ruined having the financial capacity to sue; and (2) the individual or organisation who has unfairly criticised the person who made the statement being identifiable, present in the jurisdiction, and having the financial capacity to pay damages.

The employer of the person who makes the comment

There are significant incentives for employers to terminate the employment of employees who are damaging their “brand”, particularly if the mob starts directly attacking the employer as well. In the United States, employment contracts are “at-will”, meaning that either party can terminate them when they want to.

Australian law is different from United States law because our history and development was so different. We don’t have a Constitutionally entrenched right to freedom of speech,6 but we’ve always had a strong labour movement.

Helen Dale has commented that Australian employment protection laws make all the difference:

It’s difficult to convey to outsiders the way industrial relations operate in Australia or the (still considerable) might of its trade unions. Australian employment law has deep roots in a 1907 legal ruling that held “fair and reasonable” wages for an unskilled male worker required a living wage sufficient for “a human being in a civilised community” to support a wife and three children in “frugal comfort.” A skilled worker should receive an additional margin, regardless of the employer’s capacity to pay.

In addition to ensuring workers are well paid, Australia’s Fair Work Act makes it illegal to sack an employee on a large number of grounds; religion is only one. It protects the hard-won trade-union-derived right to engage in activity with which one’s employer disagrees outside work hours with real teeth. It evinces an historic and on-going national obsession with fairness.

Hence, s 385 of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) provides that a person may have been unfairly dismissed, including, under s 385(b), if “the dismissal was harsh, unjust or unreasonable.” In considering whether a dismissal was harsh, unjust or unreasonable, the Fair Work Commission must take into account, under s 387(a) of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth), whether there was a “valid reason” for the dismissal. Importantly, there must be a relevant connection between the employee’s conduct and their employment relationship,7 and employers do not generally have a right to regulate the private activities of employees.8 In Rose v Telstra Corporation Ltd, a case where the employee got into a fight with a co-worker at nightclub on the weekend, it was said:

It is clear that in certain circumstances an employee’s employment may be validly terminated because of out of hours conduct. But such circumstances are limited,:

- the conduct must be such that, viewed objectively, it is likely to cause serious damage to the relationship between the employer and employee; or

- the conduct damages the employer’s interests; or

- the conduct is incompatible with the employee’s duty as an employee.

In essence the conduct complained of must be of such gravity or importance as to indicate a rejection or repudiation of the employment contract by the employee.

Of course, this framework has been challenged by social media—precisely because social media breaks down the division between private and public life—and there are Australian cases where employers have been found entitled to sack employees for posts on social media, even where those posts are private or “locked”.9

“Brand management” in the days of social media is a serious business. Often workplaces have clauses incorporated into their contracts or policies which require employees to behave in certain way.

The Australian example indicates another piece of the legal response to this puzzle may involve giving employees recourse against employers who seek to summarily dismiss them without proper consideration. The line between when allegedly offensive conduct is private or public remains very difficult to draw, however.

Conclusion

I don’t attempt to provide a definitive account of the issues here—I’ll save that for an academic publication—but I did want to make it clear that this is a very complex problem which involves different actors, and different laws. It may be that there are issues I haven’t thought of. Feel free to raise any you spot.

I’m aware that I haven’t even touched on issues of freedom of speech, disagreement, and what we want to achieve in a civil society. I started to deal with these matters, and then realised I was opening a can of worms, so I’ve slammed the lid on that can for now.

It will be difficult for any government to legislate to stop social media mobs, and the law will need to achieve a delicate balance. While stronger protection for employees and actions based on economic torts might help prevent egregious instances of social media mobbing, I suspect that the lever for producing better behaviour overall may rest with the removal of immunity from social media companies. However, that’s a matter for United States law. And it will change the Internet as we know it. Is that what we really want?

The third way of gaining status—and the one which drives me—is competence, namely being the best at something, and useful to the group thereby. I like to be useful.

Chimps = very proactively aggressive. See eg, Chelsea Whyte, ‘Chimps beat up, murder and then cannibalise their former tyrant’ New Scientist (30 June 2017); Michael L Wilson at al, ‘Lethal aggression in Pan is better explained by adaptive strategies than human impacts’ (2014) 513 Nature 414. Chimps are also Machiavellian: Christopher Flynn Martin et al, ‘Chimpanzee choice rates in competitive games match equilibrium game theory predictions’ (2014) 4 Scientific Reports 5182 (https://doi.org/10.1038/srep05182). This is what you learn when you write a book about animals and the law and decide to find out why chimps are ferae naturae. Do not have a chimp as a “pet”.

Incidentally, if you do get piled on—I admit it’s happened to me occasionally, in a small way—my advice is count them. Often there’s fewer direct attackers than it seems at first.

My drunk self tends to say, “I love all you guys,” hug everyone, dissolve into tears, then fall asleep. Still you can’t be too careful.

2022-Ohio-1079.

An implied right to freedom of political communication has been found by the High Court of Australia to be present in the Constitution, as an essential aspect of representative democracy, thereby restricting the extent to which the Commonwealth and the States can legislate on certain matters: see Nationwide News Pty Ltd v Wills (1992) 177 CLR 1; Australian Capital Television Pty Ltd v the Commonwealth (1992) 177 CLR 106; Unions NSW v New South Wales [2013] HCA 58; Brown v Tasmania [2017] HCA 43.

Rose v Telstra Corporation Ltd [1998] AIRC 1592.

Appellant v Respondent (1999) 89 IR 407, 416.

I have derived considerable assistance in writing this piece from consulting Justin Pen, ‘‘Never Tweet?’ Social Media and Unfair Dismissal’ (2016) 41(4) Alternative Law Journal 271-274. Any errors are my own.

Someone has brought to my attention the possibility that this is in fact designed to silence social dissidents, rather than to facilitate civil disagreement: https://edition.cnn.com/2023/05/12/asia/cancel-culture-law-singapore-intl-hnk/index.html

An added consideration when furthering a conversation about the roles/goals of social media, intended as a means, is to address its ultimate, but maybe not desired, 'end:' Placing everyone back onto the same 'island,' and thereby, abolishing what once was given primacy - Privacy. Within such a conversation, one needs to apply both the hermeneutic of suspicion and the hermeneutic of retrieval.