Australia Day: Rapscallions, Rum and Rebellion

Why that date and how did it start?

On 26 January, we celebrated Australia Day, Australia’s national holiday. These days, it is run by the Australia Day Council and is intended to raise national pride. However, it has only become a national holiday recently, since 1994. For many years, there has been controversy about the date. Some Indigenous people have called it “Invasion Day” and demanded that the date be moved.

A few years back, my mother and I became curious about why that particular date was chosen and when that choice was made. This post is the result of our research.

You might think that 26 January was the anniversary of the date upon which Australia was formally and legally colonised.1 You would be wrong. Australia was not formally colonised by the British until 7 February 1788, when Governor Arthur Phillip read out the formal proclamation of the colony. Nor does it reflect the date when we became a separate country and a Federation of States (1 January 1901).

26 January 1788 was the day when the First Fleet landed at Sydney Cove and Phillip raised the Union Jack and toasted the health of King George III.

The first officer from the New South Wales Corps to set foot in Sydney Cove was reputed to be one Major George Johnston.

Exactly twenty years later, on 26 January 1808, Johnston, now the commander of the New South Wales Corps, marched on Government House in Sydney, in Australia’s only military coup, dubbed the “Rum Rebellion.” He removed the incumbent Governor, William Bligh—he of the Bounty mutiny—and placed him under house arrest.

I do not think it is a coincidence that “Anniversary Day” (as 26 January was then known) began to rise in popularity in the years after Bligh was appointed governor, while Johnston was commander of the New South Wales Corps.

Indeed, it seems possible that when Bligh made his secretary write a letter on 25 January 1808, summoning Johnston to appear before him at 9am the next day, one reason why Johnston did not attend or reply was that he had already been celebrating Anniversary Day. Bligh’s notes on his secretary’s letter say,

“In place of any letter being written in answer to my above letter, Thomas Thornby, one of my bodyguard, who carried it, returned and said:—“Major Johnston’s compliments to Mr. Griffin [Bligh’s secretary]. That he was sorry he could not write an answer to him to the note he had received; that he was dangerously ill, and it would endanger his life to come into camp; his right arm was tied up, and he said he had been bled…”2

Johnston had been celebrating in the army mess, where he had been the main toast, as the first officer to step ashore. He had fallen from his gig while driving home, and had seriously bruised his face, and his arm was in a sling. It was perhaps Australia’s first prominent drink-driving accident.

What led to Johnston’s coup? Put bluntly, the first twenty years of the colony of New South Wales were chaotic. We don’t even have the final instructions given to Phillip about the establishment of the colony, although draft instructions have been found in England.

The First Fleet had only £300 in English currency (held by Phillip) and coins brought by passengers (including English guineas, shillings and pence, Spanish dollars, Indian rupees, and Dutch guilders). It was intended that officers would be paid in goods and provisions, and free settlers would be self-sufficient. Of course, convicts did not want to work for no reward. A complex bartering system arose, using food, clothing, and alcohol. Convicts and lower ranking military personnel were paid in goods, with the prized but rare payment being rum.3 The New South Wales Corps became known as the “Rum Corps” as a result.

Lack of workable currency was a persistent issue in the early Australian colonies. An early solution was to cut up Spanish dollars and to use the pieces as currency, as reported by a passing American sailor, Robert Murray, in his diary in 1794.4 Murray suggests that the person who came up with this was my convict ancestor, Simeon Lord:

Some persons who are acquainted with the parties say it was discovered by the ingenious Mr McA— [John Macarthur] one of the Lieutts. in the Corps, and the Governor of Parramatta. others, that it was found out by a convict acting as a clerk in the service of the Adjutant [Thomas Rowley], for which he is said to have had a present of a bottle of Grogg and a pair of military shoes from that Gentleman.—but the majority say the Master discovered it himself-Certain it is, that the discovery has been of the greatest utility, and is now, universally adopted.—5

I am biased, but given Lord’s later activities and financial inventiveness, I think that it is entirely in character for him to have developed this method. Later, Governor Lachlan Macquarie made the “holey dollar” (an adapted Spanish dollar) the Australian legal tender from 1813 to 1822.

Captain Thomas Rowley, mentioned above in Murray’s diary, had arrived in Sydney in 1792 on The Pitt. Rowley, then in his forties, was allowed to choose convicts to be his “servants.” He chose eighteen-year-old Elizabeth (Betsey) Selwyn (who had been on The Pitt with him) and nineteen-year-old Lord. Both convicts were thieves. Selwyn purportedly bore Rowley five children. My mother and I are descended from Selwyn’s fifth child, Eliza Rowley.

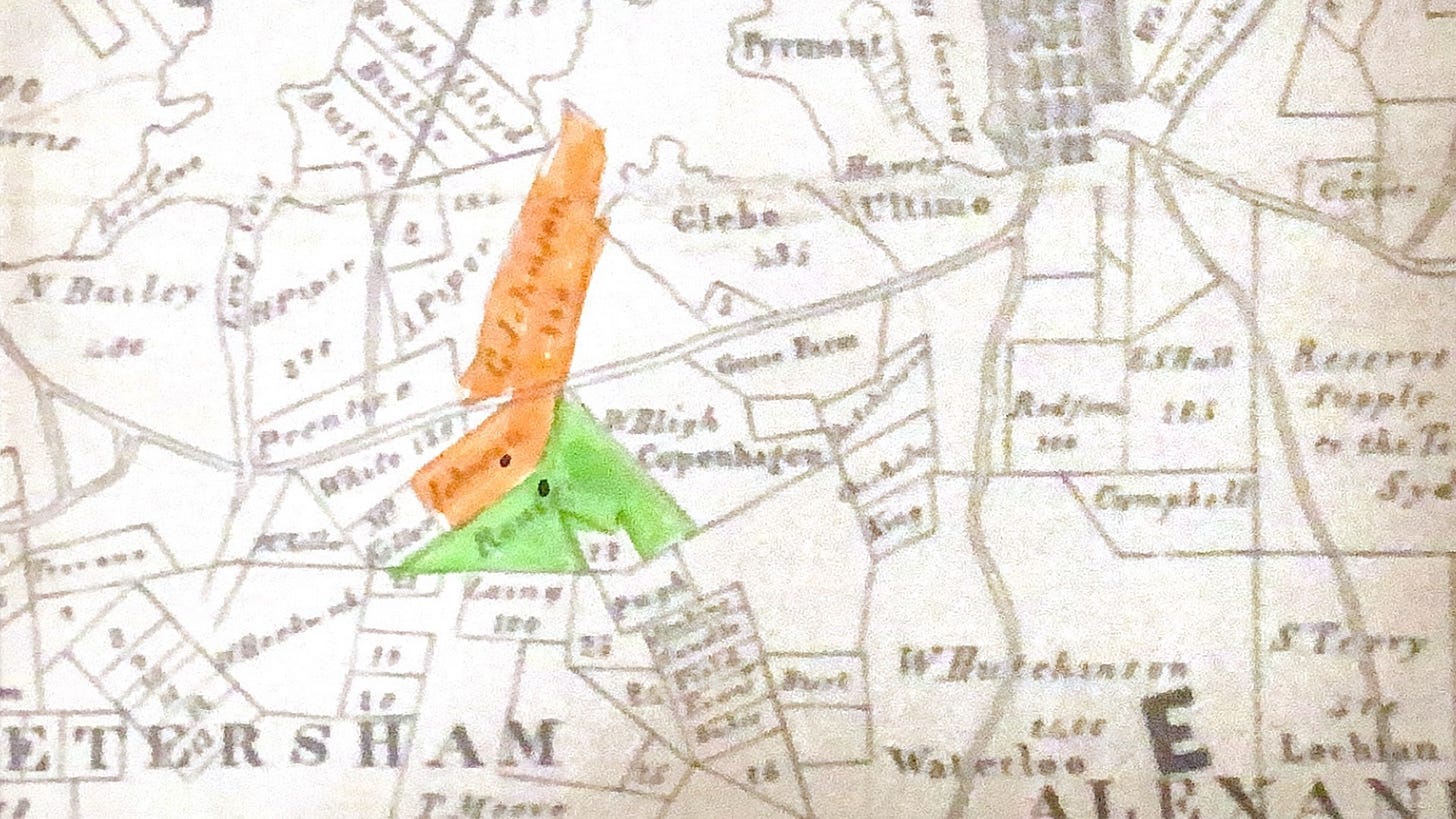

Rowley’s farm, Kingston Farm, was next to Johnston’s residence, Annandale House. Johnston had also chosen a convict to be his “servant”: a Jewish thief named Esther Abrahams, who already had a daughter called Rosanna, born in Newgate Prison in 1787. Abrahams then bore Johnston seven children, and married him in 1814.

However, as I have already written, Eliza Rowley’s parentage was a little more complex. People descended from Eliza Rowley (including me and my mother) have been genetically matched to many of Lord’s descendants on an ancestry site. It is therefore likely that Lord was Eliza Rowley’s true father, not Rowley, as there is no other way for us to be related to Lord’s descendants. When Eliza Rowley was conceived, Lord had left Rowley’s service, and had set up his own trading enterprise. Whether anyone knew of Eliza’s true parentage is unclear. Rowley died in 1806, two months before Bligh arrived, when Eliza was two years old.

The celebration of 26 January as “Anniversary Day” was a creation of emancipated convicts who wanted to celebrate their new life in Australia.

I have at least eight convict ancestors, including Lord and Selwyn. All of them, without exception, had a better life in Australia than they would have had if they had stayed in England. This is particularly true of the six who were transported between 1791 and 1803. Lord became a magistrate and successful entrepreneur and married another convict, Mary Hyde. Selwyn struggled with money after she was “widowed” but lived into her seventies. My ancestor, George Barnett, a teenage orphan pickpocket, married another convict, Hannah Manley. They had seven children. George owned a house in The Rocks and ran a carting business. Mary Brown, a diminutive “lady of negotiable virtue”, was sentenced to death for hitting a client over the head and robbing him, but her sentence was transmuted to life transportation. She married William Goodwin, a weaver who had been transported for stealing a side of beef. Goodwin had been on The Pitt too. He became a soldier in the Loyal Association (a civilian militia) of which Rowley was commandant. He then became a respectable constable for twenty years.

In the early colony, there was no sharp division between officers, settlers and convicts. When Bligh arrived in July 1806, his mission was to close down private enterprise, stop the sale of “grog”, and re-establish New South Wales as a penal colony. He was horrified to see that the officers and the convicts were so intermingled.

Bligh swiftly managed to annoy almost everyone, including Johnston; John Macarthur, the powerful and splenetic former Rum Corps officer; and Lord, whom he placed in gaol for questioning his decisions about Lord’s trading ship.

In October 1807, Johnston—otherwise known for his pleasant, easy-going manner—wrote to the military secretary of the Duke of York, complaining that Bligh had interfered “in the interior management of the Corps by selecting and ordering both officers and men on various duties without my knowledge; his abusing and confining the soldiers without the smallest provocation and without ever consulting me as their commanding officer; and again, his casting the most unreserved and opprobrious censure on the Corps at different times in company at Government House.”6 Bligh made himself very unpopular with the New South Wales Corps.

Bligh’s final mistake was to charge Macarthur with an offence relating to one of his ships:

Macarthur was arrested and released on bail of £1,000. Macarthur immediately demanded that Judge-Advocate [Richard] Atkins repay a debt he had owed Macarthur for 15 years. Atkins, a non-lawyer, was notorious for his poor legal knowledge, irresolution, drunkenness, and failure to pay debts. Bligh and Atkins relied heavily on legal advice from George Crossley, a former lawyer who had been transported for perjury, because there were no free settler lawyers in the Colony.

The Court of Criminal Jurisdiction was comprised of Judge-Advocate Atkins, and six military officers, who were supposed to confer over criminal verdicts. However, when the court met on 25 January 1808, the officers assigned to Macarthur’s trial (all members of the New South Wales Corps) refused to recognise the Judge-Advocate’s authority, or to swear him in, and the trial could not be completed. Macarthur abused Atkins for failing to pay his debts, and also challenged his authority. Upon Atkins’ and Crossley’s recommendation, Bligh charged the officers with treason (a capital offence).7

Johnston might have refused Bligh’s summons to appear at 9am, but he was well enough by 4pm on 26 January 1808 to order Macarthur’s release, although he had never previously been aligned with Macarthur.8 Macarthur then wrote a petition seeking that Johnston remove Bligh, on the basis that “every man’s property, liberty, and life is endangered” and presented it to Johnston. At first, it was only signed by six people, including Macarthur, Gregory Blaxland, John Blaxland, James Badgery, James Mileham, Nicholas Bayly and one S. Lord (the only emancipated convict to sign). Bligh’s dyspeptic note on the petition states that it was signed by the above seven individuals, but “upwards of one hundred other inhabitants of all descriptions, some of whom are the worst class of life”9 signed it thereafter.

Johnston marched on Government House and put Bligh under house arrest. He later claimed that he wished to prevent Bligh from being killed by angry soldiers.10 Bligh remained under house arrest until 20 February 1809, where he escaped and commandeered a ship called The Porpoise in Sydney Harbour. Eventually, Johnston was recalled to England and court-martialled. He was found guilty but his punishment was the most lenient possible, and he returned to Australia. Governor Lachlan Macquarie took control of the colony in 1810; he also brought a regiment with him.

Michael Duffy explained in an article in The Sydney Morning Herald that the Rum Rebellion was not about grog but was about the nature of the early colony:

…it was the culmination of a long-running tussle for power between government and entrepreneurs, a fight over the future and the nature of the colony. The early governors wanted to keep NSW as a large-scale open prison, with a primitive economy based on yeomen ex-convicts and run by government fiat.

In contrast, a growing number of entrepreneurs wanted to build a vigorous economy, and sought political influence for themselves (as they would have had back in Britain). So the rebellion is important as the first major crisis in the fight between government and capital in Australia.

In any case, “Anniversary Day” celebrations lived on, with a select group of people of non-elite background. In January 1817, Isaac Nichols, another former convict and the colonial Postmaster, advertised that he was holding an “Anniversary Day” dinner party. Nichols was married to Johnston’s step-daughter, Rosanna Abrahams.

In 1818, Macquarie declared “Anniversary Day” an official celebration for New South Wales. Official “Anniversary Day” dinners were held from 1821 to 1846, in which a select group of men, such as Lord and William Charles Wentworth were involved. By the 1840s, however, celebrating convict ancestry was increasingly déclassé. In 1837, 37.7% of the population of New South Wales were convicts, but by 1847, this proportion had dropped to 3.2%.11 Lord himself stepped out of public life so that he did not taint his children’s prospects.

26 January has always been controversial, for different reasons, and its popularity has been subject to ebbs and flows. I was fascinated to discover the convict origins of the celebration. Whether that date is kept for Australia Day or not, the events which occurred on 26 January profoundly shaped the country we are today.

The word “legally” here means that for Phillip’s act to be legally valid in the eyes of British authorities at that time, he had to read out the declaration for the colony to be proclaimed.

Governor Bligh to the Officers, 25 January 1808, Historical Records of New South Wales I/VI, pg 427.

Bruce Kercher, Debt, Seduction and Other Disasters: The Birth of Civil Law in Convict New South Wales (Federation Press, 1996) pg 114.

H.C. Forster, ‘‘Tyranny, Oppression and Fraud’: Port Jackson 1792–1794’ (1974) 60(2) Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society 73. Murray was not impressed by Sydney.

Ibid, 80 - 82.

Major Johnston to Lieutenant-Colonel Gordon, 8 October 1807, Historical Records of New South Wales I/VI, pg 652.

Katy Barnett and Lynne Barnett, ‘Equity’s Darling and the Burwood Ejectment Case: a turning point in Australian Colonial law’ (2022) 96(12) Australian Law Journal 890, 894.

State Library of New South Wales and Historic Houses Trust, 1808: Bligh’s Sydney Rebellion (2008) pg 15.

John Macarthur and others to Major Johnston, 26 January 1808, Historical Records of New South Wales I/VI, pg. 434.

State Library, above n 7, pg 15.

Alex Castles, An Australian Legal History (LBC, 1982) pg. 153.

I really enjoyed reading this post, Katy. I am an immigrant to Australia, and my UK colleagues teased me that Australia is “barely civilised”.

Stories like this help understand the fragile nature of building a new society, and the reliance on specific brave and courageous individuals. It is empowering to think that our present was shaped not by “colonialism” or “patriarchy” but by person X doing what they thought was right at the time. I despise collectivism, so to describe history through the lens of sentient adults making individual choices will always appeal to me.

But I suspect that history is shaped by a thousand “sliding doors “ moments, not by ex post facto rationalisations based on Marxist analysis.

Thank you for sharing.

What is clear though is that the East Coast was claimed for Britain on 26 January. The French were still in Botany Bay so that was essential. 7 February was proclaiming what had already been carried out in practice.