Ancient customer complaints

Nanni’s dispute with Ea-nǎşir

The thing that hath been, it is that which shall be; and that which is done is that which shall be done: and there is nothing new under the sun.

Ecclesiastes 1:9, King James Version.

My students know that I have an obsession with breach of contract, remedies, and history. In these unsettling times, I decided to keep calm and carry on, by thinking about the world’s oldest known written customer complaint (dating from about 1750 BCE, ie, almost 4,000 years old).

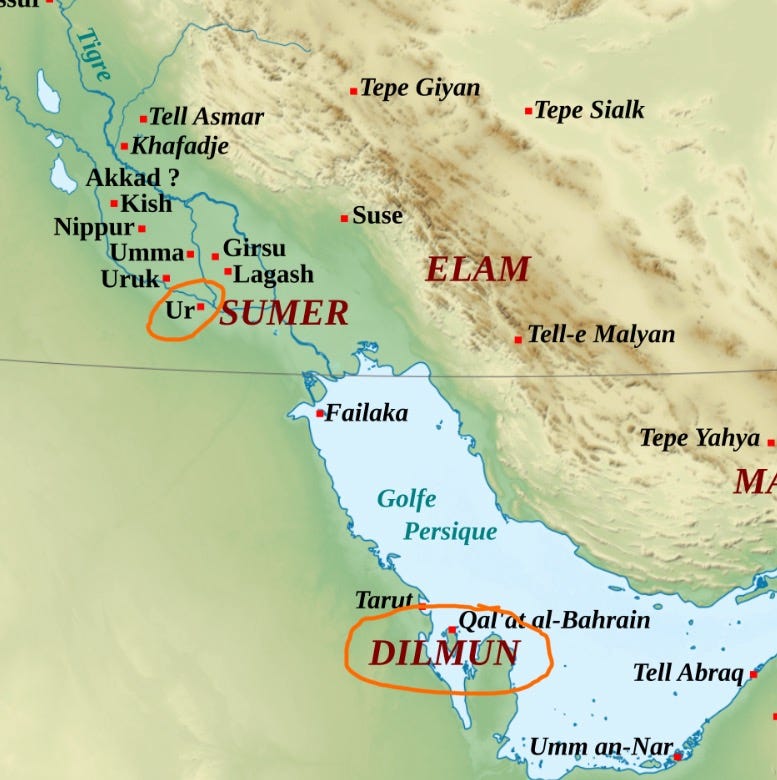

I present to you a letter from a very angry man named Nanni, who had agreed to buy some copper ingots from a merchant named Ea-nǎşir, who lived in the ancient Mesopotamian city of Ur.

The letter was written in Akkadian cuneiform. It has been translated as follows:

Tell Ea-nǎşir: Nanni sends the following message:

When you came, you said to me as follows, “I will give Gimil-Sin (when he comes) fine quality copper ingots.” You left then but you did not do what you promised me. You put ingots which were not good before my messenger (Şit-Sin) and said, “If you want to take them, take them, if you do not want to take them, go away!”

What do you take me for, that you treat somebody like me with such contempt? I have sent as messengers gentlemen like ourselves to collect the bag with my money (deposited with you) but you have treated me with contempt by sending them back to me empty-handed several times, and that through enemy territory. Is there anyone among the merchants who trade with Telmun1 [aka Dilmun] who has treated me in this way? You alone treat my messenger with contempt! On account of that one (trifling) mina of silver which I owe(?) you, you feel free to speak in such a way, while I have given to the palace on your behalf 1,080 pounds of copper, and Şumi-abum has likewise given 1,080 pounds of copper, apart from what we both have had written on a sealed tablet to be kept in the temple of Şamaş.

How have you treated me for that copper? You have withheld my money bag from me in enemy territory; it is now up to you to restore (my money) to me in full.

Take cognisance that (from now on) I will not here accept any copper from you which is not of fine quality. I shall (from now on) select and take the ingots individually in my own yard, and I shall exercise against you my right of rejection because you have treated me with contempt.2

Ur and the other Mesopotamian cities needed copper to make bronze alloys, but copper was not readily available in the area. Therefore, merchants needed to trade with Dilmun (now known as Bahrain) to obtain copper ingots. This was quite a long way away. At that time Ur was on the coast, and ideal for seafaring merchants (the Persian Gulf has since changed). Ea-Nǎşir lived in Ur during the reign of King Samsu-Iluna, the son of King Hammurabi.

Lloyd Weeks, a Professor of Archaeology, has observed in relation to this dispute:

Individual maritime trading expeditions to Dilmun, probably undertaken by Ea-nasir himself, were financed by large numbers of investors, who each contributed a small amount of capital to the mission in the form of silver rings, baskets, sesame oil, and textiles. Upon return from Dilmun, the proceeds were divided amongst the investors, who frequently complained about the quality of the copper that had been supplied to them. Although the archives from the house of Ea-nasir indicate that the trade was undertaken by private merchants, the Palace was involved in the proceedings as sometime investor, and through the collection of taxes upon the completion of the expedition.3

Presumably Nanni came from another more northerly Mesopotamian city, hence his complaints about the dangers his messengers faced in their journey to Ur. At this time, there was considerable unrest and rebellion in the region.

Remarkably, Nanni’s was not the only complaint against Ea-nǎşir!4 Several other complaints were found in his house. Men named Imgur-Sin and Arbituram also wrote repeatedly to Ea-nǎşir, begging him to transfer good copper to a man named Niga-Nanna. A man named Nar-am also complained, saying,

About what you wrote to me, now I have sent Igmil-Sin to you. (About) the copper from my purse and Eribam-Sin’s purse, put it under seal for him and let him bring it to me! Give him very good copper! Hopefully the copper in your care has not gone out. …

In another letter, an unnamed customer seeks hibilti5 (literally, “damages”) to reflect the fact that he did not get the expected amount of copper, because Dilmun units of measurement of copper were very different from the Ur units of measurement. This is an eternal difficulty facing contracts for sale of goods before standardised measurement.

Interestingly, we also have Ea-nǎşir’s letter to some irritated customers, trying to allay their fears. It seems clear that Ea-nǎşir was an entrepreneur and importer of copper.6 Why would Ea-nǎşir have kept all this documentation?

There were complex Babylonian laws dealing with commercial transactions, with different kinds of contract for different transactions. The Code of Hammurabi states the dire consequences if one did not have a written contract or a witness to a contract of sale:

§7 If any one buy from the son or the slave of another man, without witnesses or a contract, silver or gold, a male or female slave, an ox or a sheep, an ass or anything, or if he take it in charge, he is considered a thief and shall be put to death.

The kinds of contract included contracts of sale, lease, agricultural leases, barter, gift, dedication, deposit, loan, pledge, and debt. Some of the contracts for seafaring voyages in Ur at this time seem to have been unusual. While the usual trading contracts in Mesopotamia had resembled partnerships and resulted in a proportionate share of the profit, the investors in some of the seafaring trading ventures at this time in Ur did not accept any losses as a result of the failure, but accordingly, they did not get a proportionate share of the profit, only a fixed return.7

Why is Ea-Nǎşir so popular? I suspect it’s the familiarity of the roguish merchant trying to fob off disgruntled customers. He became the subject of numerous memes. This is my favourite one:

Anyway, I thought I might entertain myself by considering what Nanni’s remedies would be under common law for Ea-Nǎşir’s breach of contract, presuming the contract was subject to the law of current day Australia in the State of Victoria, because what else is a girl to do on a rainy weekend, except indulge in ridiculous anachronism? There are apparently two breaches here: the goods are defective and perhaps not fit for purpose.

Nanni seems to want the remedy we call rescission. In other words, he gets his money back, Ea-nǎşir gets to keep the copper, and the two parties go back to the position they were in before the transaction was entered into. It can be viewed as a form of “self-help” when a contract of sale goes wrong,8 and as Nanni’s request shows, it is a very natural thing to want when substandard goods are supplied.9

Nanni would want to argue that there was a misrepresentation as to the quality of the goods. He certainly seems to have unequivocally elected for rescission, given that he sent several servants to collect his bag of money, and he demanded its return. The question is whether the transaction can be truly unwound. Unfortunately, we don’t have enough detail to know (although the detail we do know is extraordinary). It seems that Nanni and Şumi-abum have paid a tithe or import duty to the temple on behalf of Ea-nǎşir, and they have made a formal declaration to this effect. It may be that this was in some way consideration for the deal, and that this part of the transaction could not be readily undone, in which case, complete restitutio in integrum cannot be made at common law,10 and even substantial restitutio in integrum as required for equitable rescission may be impossible.11 It would depend whether some form of equitable adjustment could be made to reflect the payment of the tithe. I also wonder about the one trifling mina of silver owned to Ea-Nǎşir (presumably Nanni’s initial investment in the venture). Would counter-rescission be necessary, or perhaps a set-off?

Nanni could instead affirm the contract and seek damages for breach of contract. My research ascertained that there were words for “financial loss” (ibissû) and “damages” (hibilti) in Old Babylonian so he would have a notion of what this meant.

If our law applied, there would be an implied warranty that the goods would comply with their description as stipulated by s 18 of the Goods Act 1958 (Vic), and that the goods were “fit for purpose”, as stipulated by s 19 of the Goods Act 1958 (Vic). It seems clear from the level of complaints that the goods did not comply with their descriptions and/or were not fit for purpose.12

Section 59(1) of the Goods Act 1958 (Vic) stipulates that a buyer is not necessarily entitled to reject the goods, but that they can seek a reduction in price or sue for damages for breach of contract (perhaps the unpaid one mina of silver could be accommodated by set-off). Otherwise, damages would be measured at the difference in value between the copper with which Nanni was provided, and the value of copper which met the specifications, as set out in s 59(3) of the Goods Act 1958 (Vic), which states:

In the case of breach of warranty of quality such loss is prima facie the difference between the value of the goods at the time of delivery to the buyer and the value they would have had if they had answered to the warranty.

This presumes that there is a market where the non-breaching party can mitigate their losses, perhaps by the purchase of goods which do comply with the warranty.

Section 59(2) of the Goods Act 1958 (Vic) notes that:

The measure of damages for breach of warranty is the estimated loss directly and naturally resulting in the ordinary course of events from the breach of warranty.

However, s 59(4) of the Goods Act 1958 (Vic) allows the buyer to seek further damages, even if he or she has already received a reduction in the purchase price.

This raises the interesting question of the application of the rule in Hadley v Baxendale.13 Hadley v Baxendale makes the breaching party liable for “natural and ordinary losses” which should have been in their contemplation. However, the breaching party will only be liable for “special losses” if they know of the losses at the time the contract was signed. It may be that the payment of the tithes was a natural and ordinary loss in the context of Babylonian society and beliefs—the letter seems to indicate that this was an expected consequence of the transaction—and Nanni could recover damages for this. Of course, I also can’t help wondering if Nanni lost consequential profits and incurred other reasonable costs as a result of the failure to supply quality copper. As long as those profits were an ordinary kind of profit, Victoria Laundry (Windsor) Ltd v Newman Industries Ltd14 indicates that the loss of profit and other consequential losses would be recoverable from a supplier who knew the context of the industry.

This was a fun little exercise to undertake, but it was also extraordinary to me how easy it was to apply modern commercial laws to a very ancient transaction. It’s sometimes argued that the market economy is a creation of the nineteenth century.15 I know too much about Roman law to accept this argument. This post made me think about the fact that market economies, and the problems that commercial deals raise, are even older. There truly is nothing new under the sun.

In Ur at this time, there were apparently a class of seafaring merchants known as alik Telmun. See A Leo Oppenheim, ‘The Seafaring Merchants of Ur’ (1954) 74(1) Journal of the American Oriental Society 6, 7 doi:10.2307/595475

Translation taken from A Leo Oppenheim, Letters from Mesopotamia: Official Business and Private Letters from Two Millenia (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1967) pgs 82 - 83

Lloyd Weeks, Early Metallurgy of the Persian Gulf: Technology, Trade, and the Bronze Age World (Boston: American School of Prehistoric Research and Brill Academic Publishers, 2003) pg 16. See also Oppenheim, above n 1, 7: the tithes were required as gratitude to the goddess Ningal.

See Erin Blakemore, ‘Think customer service is bad now? Read this 4,000-year-old complaint letter’ National Geographic, 31 May 2024.

W.F. Leemans, Foreign Trade in the Old Babylonian Period as revealed by texts from Southern Mesopotamia (Leiden: Brill, 1960) pg 49.

Ibid, pg. 51.

Oppenheim, above n 1, 8 - 9.

Alati v Kruger (1955) 94 CLR 216, 225-226.

For a (comparatively) modern, more complex version of this see Clough v London and North Western Railway Co (1871) LR 7 Ex 2.

Clarke v Dickson (1858) El Bl & El 148, 120 ER 463.

Alati v Kruger (1955) 94 CLR 216.

The consumer guarantees in the Australian Consumer Law would not apply because the goods are intended to be used for manufacturing purposes (i.e. the production of bronze).

(1854) 9 Ex 341, 156 ER 145.

[1949] 2 KB 528.

Eg, Karl Polanyi, The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time (Boston: Beacon Press, 2001). Cf David Graeber, Debt: the first 5000 years (Brooklyn, NY: Melville House Publishing, 2013). I disagree with Graeber’s analysis in some regards, but his recognition of the ancient origins of debt is very welcome.

I'm starting a copper shipping business called Ea-nǎşir Pty Ltd. Customer feedback must be carved in stone tablets.

Wonderful Katy. I have written about customer complaints but have done nothing as thorough as this.