A 200+ year old scandal…

Convicts, concubines and Captains

Because it’s Mother’s Day in Australia today, I’m posting this in honour of my marvellous Mumma. Thanks for checking I got the details right, Mumma.

My family lived in England from 1977 to 1979, and then again 1991 to 1994. We’d be asked, “Where do you come from?” Other than “Australia,” we didn’t have an answer: we had a vague notion that we had some English, Scots and Irish ancestors, but that’s about it. When we got back to Australia, Mum began her genealogical research.

She discovered that our ancestors were far more fascinating than we realised (she’s still researching, uncovering more and more interesting things). Among other things, she discovered that some of my ancestors had been involved in a twenty year legal dispute, involving wills, transfers of property, trusts, debt, good faith purchasers for value, rescission, libel, and the division between common law and equity. We ended up writing a paper on it, and it was published in the Australian Law Journal last year.

I’m going to tell you a part of the story which didn’t belong in a Law Journal (except in footnote six, where we allude to it). Among other things, Mum discovered a two-hundred-year old scandal.

One of our ancestors was (purportedly) a man named Captain Thomas Rowley, in his forties when he arrived in Sydney in 1792, on the Fourth Fleet, on the Pitt. Rowley was an Adjutant in the New South Wales Corps, known as the “Rum Corps” for its role in trading rum in the early Colony, where it was one of the currencies used to facilitate trade. As an officer, Rowley was assigned two convicts from the Pitt as his servants, 19-year-old Elizabeth Selwyn (known as “Betsey”), from Gloucestershire, and 20-year-old Simeon Lord, from Yorkshire. Both young convicts had been transported for theft.

Rowley’s wife had died during the voyage to Australia, and it seems he formed a relationship with Selwyn either during the voyage, or shortly after they arrived in Australia. She was listed as his “housekeeper” in censuses, but bore him five children: Isabella (b. 1792), Thomas (b. 1794), John (b. 1797), Mary (b. 1800) and Eliza (b. 1804). I am descended from Eliza Rowley, Selwyn’s fifth child. Selwyn is my great-great-great-great-great grandmother.

Selwyn’s first four children were baptised, with Rowley named as their father. No record of Eliza’s baptism exists. Was this a mere oversight, or were the reasons for this? We will never know. However, DNA analysis indicates that the descendants of Eliza Rowley (including myself, my sister, my mum and my late grandfather, but also other descendants of Eliza outside our direct family) are, in fact, genetically related to descendants of Simeon Lord. Therefore, Simeon Lord was my great-great-great-great-great grandfather, not Thomas Rowley. It is not clear whether anyone at the time realised that Eliza was Lord’s child.

Notwithstanding this, Rowley acknowledged Eliza and the four other children as his legitimate children in his will, and left his property to them and Selwyn, although he never married Selwyn.1 He mentioned his children with affection in a letter to his friend Captain Henry Waterhouse, but he never mentioned Selwyn, so it is unclear what the relationship between them was. Nor is it clear what the relationship between Selwyn and Lord was, either.

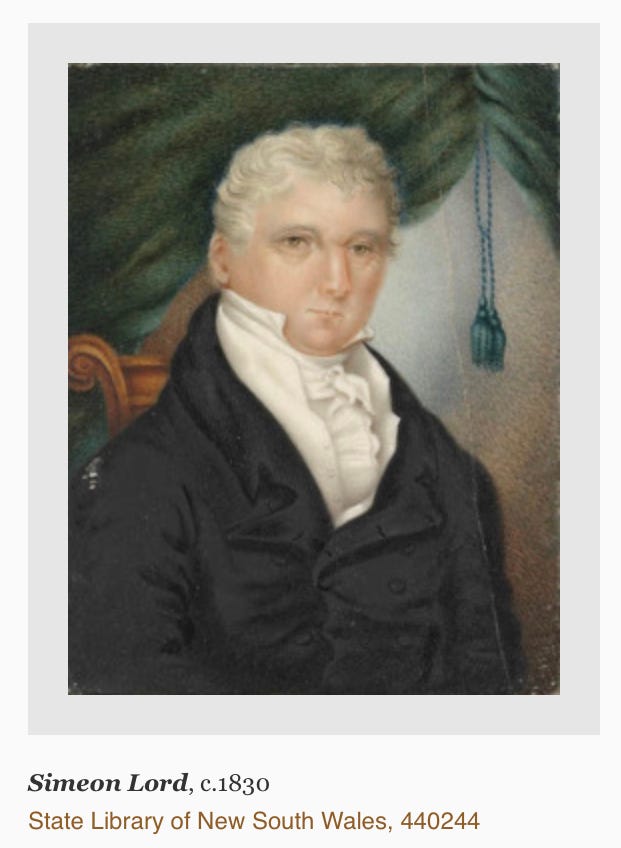

Simeon Lord is a fascinating character. Initially Lord traded for Rowley but he was so skilled at trading that he was emancipated early, and set up his own household. The Australian Dictionary of Biography reports:

Emancipated early and helped by his master [Rowley], Lord seems to have begun his mercantile career as one of the shadowy figures who retailed spirits and general merchandise bought in bulk by officers of the New South Wales Corps. In September 1798 he bought a warehouse, dwelling house and other buildings on what is now the site of Macquarie Place. In 1800 he was one of the petitioners who sought the governor's permission to buy merchandise direct from the ship Minerva and so to by-pass the officers' ring. Next January he was appointed public auctioneer, and captains of vessels used him increasingly to sell their wares and as a general agent. Profitable though this was, Lord sought for years to import his own cargoes, preferably in his own ships.

Later the Biography concludes:

Shrewd, unprincipled, impudent, a formidable litigant, a centre of controversy for many years, [Lord was] often generous, capable of bold and imaginative designs…

Lord eventually stepped out of public life, so that his eight children and two step-children with another former convict, Mary Hyde (with whom he began a relationship in 1805, and married in 1814) could establish themselves without the shadow of their convict parentage hanging over them.

Lord was also one of the seven initial signatories to a petition demanding the removal of Governor William Bligh,2 and the only former convict among the signatories. The petition implored Major George Johnston of the New South Wales Corps to arrest Bligh on the basis that “every man’s property, liberty, and life is endangered”. Bligh had managed to unite the disparate factions of early Colonial New South Wales against him: Lord was at frequent loggerheads with John Macarthur, the former Rum Corps officer and architect of the petition (formerly featured on the Australian $2 note), and both were at loggerheads with Dr John Harris, who had become a central figure in Governor Gidley King’s efforts to curtail the rum trade.

In Australia’s only military coup, the Rum Rebellion, on 26 January 1808, Bligh was arrested, and Johnston appointed himself as Lieutenant-Governor. Johnston’s rule ended when Lachlan Macquarie was appointed the fifth Governor of New South Wales, two years later, in 1810. Lord was made a magistrate by Macquarie, and helped to form the Bank of New South Wales.

Lord was also a serial litigant, single-handedly doubling the amount of litigation in the Colony.3 The Colony of New South Wales suffered from a severe shortage of currency from its very inception, with the result that almost everyone, regardless of status, was constantly in debt, for decades, and the colony developed its own special rules for debts.4 Private promissory notes indexed to amounts of produce became the dominant method of payment.5 While the English pound sterling remained the basic money of account,6 in the promissory notes, the payment was tied to provision of products, particularly wheat and stock, which effectively became currencies. The practice was to divide the sterling value of the promissory note by the current selling price of a bushel of wheat (for example) as fixed by the general orders, and make the note out for the corresponding number of bushels.

Lord tried to avoid his debts by suing his creditors, but he also frequently represented others in court, although he was not a qualified lawyer. But then, none of the judges of the Court of Civil Jurisdiction were lawyers either: one of the few qualified lawyers in the colony was the convict and perjurer, George Crossley.

My favourite is Lord v Palmer,7 where Lord represented an absent merchant, and which went all the way up to the Privy Council. It contains the following gems of argument. To the Court of Civil Jurisdiction, Lord said:

Gentlemen, I have trespassed a good deal on your time and regret most sincerely the occasion, but you will find first, that like my opponent, I have travelled into law cases, obsolete statutes, and the remoter pages of antiquity, to bewilder you with irrelevant points. My cause is the cause of equity and justice. Yours is the province to decide upon it. If I was in the habit of consulting law books, I might possibly discover cases that would support me, but I rest my pretensions on that principle of justice, to which I appeal, and which, I am sure, presides in your breasts, as judges, and men of honor and integrity.

This argument is entertaining, because Lord’s assertion that he was not in the habit of consulting law books is utter nonsense. After the Rum Rebellion, when the colony sought to ascertain the legality of the coup, only one person in the colony had an up-to-date version of Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England, and it was not anyone in the Colonial government. Lord generously offered to loan his copy to Bligh, who accepted.

There was then an appeal to Governor Gidley King, in which Lord said:

Your Excellency's dutiful memorialist is well aware that no sophistry that can be extracted from the remote ambiguities of law or that may be fabricated by any of its subtle professors, will for a moment impose upon your Excellency's judgement, or disturb that system of equity and impartiality which has uniformly distinguished your Excellency's adjudications and which your memorialist is found to rely, as his undoubted security for justice...

The part which particularly tickles my fancy is the phrase “may be fabricated by any of its subtle professors…”

I do wonder what Lord would have thought, had he known one of his descendants became a law professor? I suspect, given his general character, he’d have been proud, but he would also have immediately hit me up for advice.

It was Rowley’s will that gave rise to the litigation Mum and I discuss in our paper, as Major George Johnston and Dr John Harris were the executors of Rowley’s will, but shortly after Rowley’s death, they became involved in a military coup and did not properly administer the will.

The same Bligh who had been captain of the Bounty before Fletcher Christian and his men famously mutinied. It seemed that wherever he went, Bligh was divisive.

Bruce Kercher, Debt, Seduction and Other Disasters: The Birth of Civil Law in Convict New South Wales (Federation Press, 1996) pg 16: Kercher notes that Lord was responsible for an extraordinary number of Court of Appeal and Privy Council cases, apparently aimed at delaying payment.

Bruce Kercher, ‘Resistance to Autocracy’ (1997) 60(6) Modern Law Review 779.

Kercher, Debt, Seduction and Other Disasters, above n 3, 131-42; Frank Decker, ‘Bills, notes and money in early New South Wales, 1788–1822’ (2011) 18(1) Financial History Review 71.

Kercher, ‘Resistance to Autocracy’, above n 4, 836 notes “Locally born people were known, derisively, as currency and those who came freely from England as sterling. The sting was that currency was always doubtful, always inferior, always discounted when exchanged for sterling.”

[1803] NSWSupC 3; [1803] NSWKR 3 (7 July 1803).

Captain Thomas Rowley is my 5th great grandfather :).

I now live on Thomas Rowley's estate. I am trying to find out when he sold his land to form kingston farm. this history thing is amazing