In praise of books

More on how academic incentives have gone awry

I’ve been quiet lately because I’ve had two book projects to finish by the end of April: an updated version of a legal treatise and a jointly edited essay collection.

I confess that I had a rant in the preface of the treatise:

At a time when the salience and worth of doctrinal academic research has come under fire from many corners, I believe that black letter law academics can and do provide an important service to the legal community more generally. Unfortunately, it seems that the global expansion of the “publish or perish mentality” has meant that some “research outputs” are prioritised over others. In research metrics, the value of treatises and textbooks can be overlooked, because some mistakenly consider that they do not produce “new discoveries.” To this, I first respond that the role of academics is not only to make new discoveries. We are also custodians of knowledge and teachers, and hence there is real value in describing the accrued and evolutionary wisdom of the law. Secondly, the law is changeable, and keeping on top of its ever-changing flows in multiple jurisdictions is a life-long mission of discovery. Thirdly, academic treatises and textbooks were vital to my understanding of the law when I was a student and a young practitioner, and they remain vital now.

My understanding from conversations with legal publishers is that it’s becoming increasingly difficult to find academics who will write treatises and textbooks. Some useful works are at risk of falling into abeyance, as authors retire and no one is willing or able to replace them. Moreover, in fields like mine, accessible books written for the general public are not valued either.

Academic incentives currently favour journal articles (particularly in top international journals) and (in my field) highly theoretical monographs. The push to produce “new discoveries” is a product of World War II and the Cold War, when Western governments (beginning with the United States) sought to incentivise universities to produce new scientific discoveries, to ensure that the West kept up with the Soviet Union.

They did this by the provision of government grants. Of course, they did not want to give grants to people who were not worthy. How to measure academic worth? The government measured the worth of scholarship by requiring a proven track record of publications, work that was widely cited by others, and they demanded peer review of new journal articles (to check they were reputable). Although this model was first applied in science, technology, engineering and mathematics disciplines (STEM), it now applies across the board, including to humanities, arts and social sciences (HASS).

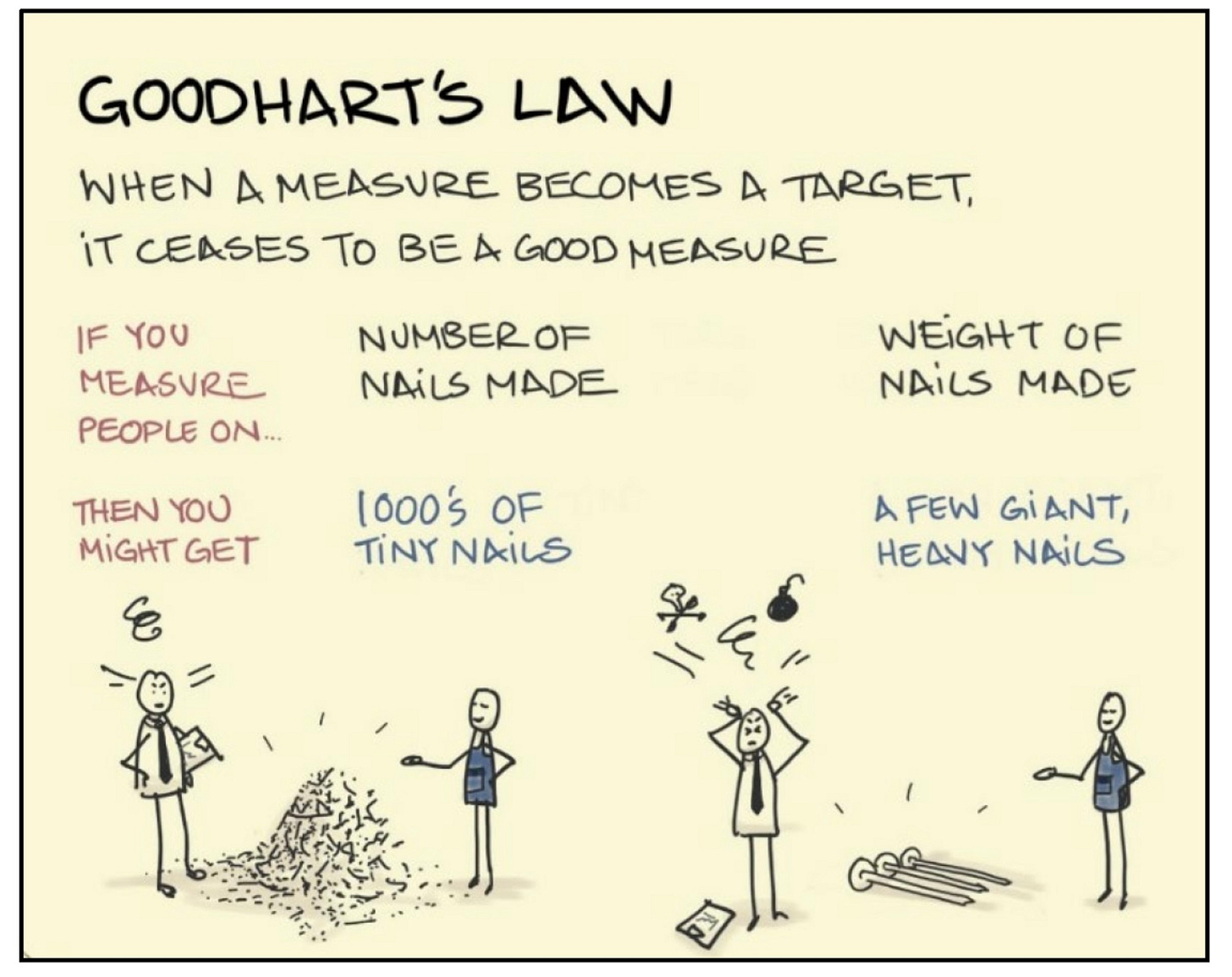

Goodhart’s law states “when a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.”

When the incentives were put in place, they might have been a good measure of academic worth. However, once these measures became a target, then they ceased to be an effective measure. I personally believe that many of the problems with academia can put down to the unintended perverse incentives arising from how we now measure worth in academia. Currently, incentives prioritise discovery and research over teaching or the custodianship of existing knowledge. This is why treatises and textbooks are regarded as less worthy.

Something has to shift with the academy. Additional governance structures and regulation won’t make a difference; indeed, these will just contribute to the ballooning bureaucracy which already exists to ensure universities conform with government requirements and regulations. Everything is awry, and it’s all down to the incentives.

A recent article by Jason Matchett in The Australian suggested that the fix to the lack of emphasis on teaching is to make university lecturers undertake a diploma in teaching, or at least some teaching training.

I would recommend that some teaching training be given to lecturers. I learned to teach on the job. I was perhaps a natural teacher: my mother was a high school teacher and one of my sister’s and my favourite games was “schools” (with me as the teacher). I began as a Law Students’ Society tutor and tutor with the Koori Students’ Liaison Unit in 1997, and then tutored at various university colleges while I was in practice. When I left practice, I was a sessional (adjunct) academic for four years, and then I was hired on an ongoing basis when I finished my PhD. I was also lucky to be mentored by senior colleagues; I have tried to pay that forward by mentoring others (both formally and informally).

I undertook the Melbourne Teaching Certificate in 2012, a six month course with our Centre for the Study of Higher Education. This was absolutely ideal for my circumstances—I could do it while teaching and apply the lessons I’d learned in my classes. I found it immensely valuable. I still use the techniques I learned. I would recommend it for everyone.

We have to be careful, however, with the hurdles we impose upon academics. An academic with an ongoing position has already undertaken postgraduate study, typically up to PhD level. The three years while I was doing my PhD were very financially difficult. If I had to do a Diploma on top of that, I would not have become an academic, particularly given that I could jump back to practice. There is a risk that by imposing such a barrier, you incentivise those who have practical skills to leave the academy, particularly if people with practical skills can earn far more money outside the academy. This is a persistent problem in some fields as it is.

What’s the fix? I don’t have any easy answers, but at a minimum, I believe the academy must resist “publish or perish” as a measure of success. It creates an illusion of productivity and innovation, but I think it has led us down the wrong path. It means that the measure of success is, effectively, how popular you are with other academics. This is not always a good measure of success or of quality work.

Moreover, the push for new discovery should not be our only focus. Not all of us are Einstein, nor should we be expected to be. I wonder how someone like Einstein would fare in the modern academy. I suspect he’d be very unhappy.

The past cannot be ignored, and in fact, as I tell my students, by its past shall you know it. Often I can only fully explain legal principles by explaining the history behind them. I am dismayed by much activist “history”, which presents a cartoon version of the world with “goodies” and “baddies” and lacks nuance. Proper history recognises that people have complex reasons behind their actions, and that often they think they are doing the right thing. Sometimes, by doing what they believe is the right thing, people commit terrible wrongs. Activists should sit back and take note. The only certain law is the law of unintended consequences.

Academics must also recall that we are custodians of knowledge. Our role is not just to theorise about what might be, and to explore those theories, but to conserve the knowledge we have collected about what is (as far as we know right now). We need to convey that knowledge clearly to those in the field, and to the general public. That is a role of much honour and worth, even if the incentives don’t currently reward it.

Another great post, Katy. Teaching contract law has made me realise how few textbooks are truly written with student learning in mind. I still rely heavily on McKendrick’s Contract Law, but recently noticed he’s now Emeritus-which made me wonder: who will take up the mantle next? We desperately need authors who can write with clarity and accessibility, not just for students but also for early-career academics. The incentives, of course, are skewed as in many professions, the more socially useful the work, the less it's rewarded. Maybe writing a good textbook is a bit like being a schoolteacher: vital to the system, but undervalued.

I was cheeky, and sent it to the production editor of the ALJ. It could do with a wide audience.